Candles surround a makeshift memorial in Ottawa on Jan. 9 to honour the victims of Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, which the Iranian military shot down near Tehran the day before.Dave Chan/Getty Images/Getty Images

On Jan. 8, the Iranian military shot down Ukraine International Airlines flight 752, killing 176 people on board, including 57 Canadians. The passenger plane was fired on while en route from Tehran to Kyiv. Several hours earlier, Iran had launched missiles at U.S. and coalition military bases in Iraq in retaliation against the assassination of military commander General Qassem Soleimani.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was given no warning by the U.S. about the drone strike that killed the top Iranian general. “The U.S. makes its determinations,” Mr. Trudeau told Global News. “We attempt to work as an international community on big issues. But sometimes countries take actions without informing their allies.”

Shortly after the strike on Gen. Soleimani, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo suggested that the Iranians were planning to attack U.S. targets. “There was, in fact, a set of imminent attacks that were being plotted by Qassem Soleimani,” he told former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice during an event at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. “It was unmistakable.”

President Donald Trump repeatedly asserted that the Iranian general was planning to attack as many as four U.S. embassies. However, Defence Secretary Mark Esper told CBS he had not seen evidence detailing any specific target, saying only that he believed Iran would likely have focused on the embassies.

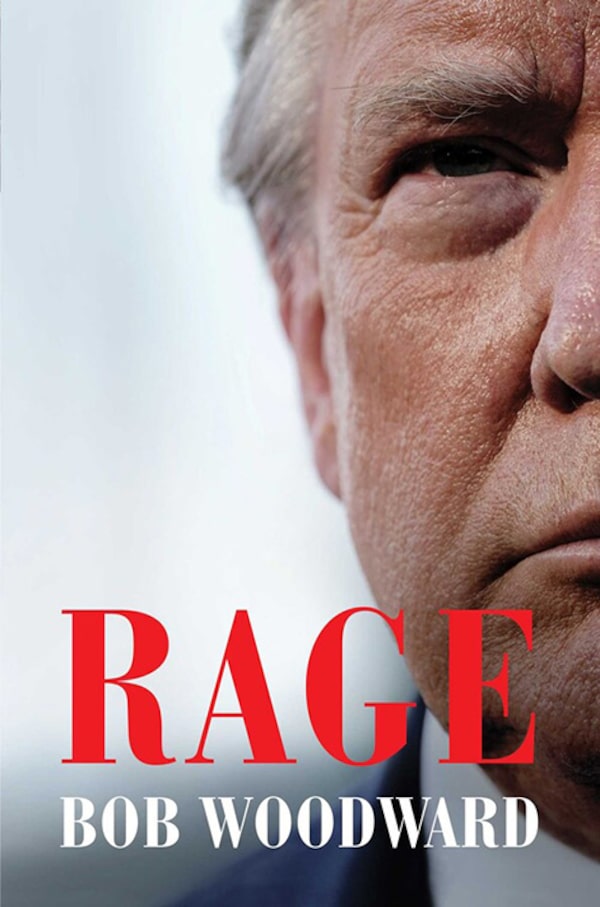

The decision to kill Gen. Soleimani is among the events covered by journalist Bob Woodward in his book, Rage, published on Sept. 15. Mr. Woodward conducted 18 interviews with the President for the book and was also given access to many top officials inside the White House.

Excerpted from Rage Copyright © 2020 by Bob Woodward. Reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

At left, flowers surround a portrait of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani at the Iranian embassy in Minsk on Jan. 10, two days after his death. At right, President Donald Trump and Senator Lindsey Graham play golf in Sterling, Va., in July. Gen. Soleimani was a topic of conversation between the men at another golf game in Florida a few months earlier.Reuters, The Associated Press/Reuters, The Associated Press

“I’m thinking of hitting Soleimani,” President Trump said, pulling his golfing partner Senator Lindsey Graham aside on the afternoon of Monday, December 30, 2019. They were on the front nine of Trump International Golf Club in West Palm Beach, Florida, four and a half miles from Mr. Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate and club. Iranian General Qasem Soleimani was the head of the Revolutionary Guard’s violent and covert special operations division known as the Quds Force. He was widely considered the most powerful man in Iran after Ayatollah Khamenei, and the driving force behind Iran’s terrorist acts overseas.

One of Gen. Soleimani’s militias had just killed a U.S. contractor in a missile attack in Iraq; the next day, the situation would escalate into a siege of the American embassy in Baghdad.

“Oh, boy, that’s a giant step!” said Mr. Graham, unnerved. Killing Gen. Soleimani would be an unexpected play, and a potentially dangerous one.

Gen. Soleimani had menaced the United States for decades.

Since 2007, he had been under surveillance by a specially formed U.S. intelligence cell created to target and stop the Quds Force from providing material and training to Iraqis fighting against U.S. forces.

Over time, Gen. Soleimani became known as one of the most dangerous people in the Middle East, more in control of Iran’s foreign policy than its minister of foreign affairs.

Gen. Soleimani had been in Mr. Trump’s sights ever since retired general and former vice chief of staff of the Army Jack Keane told him while he was still president-elect that Gen. Soleimani had given Shia militias in Iraq “an advanced IED developed by his engineers and scientists that could penetrate any known equipment on the battlefield,” even a tank. Hundreds of American soldiers had been killed and wounded by the devices.

Mr. Keane told Mr. Trump that President George W. Bush’s national security team had asked Mr. Bush to authorize the destruction of two bases in Iran where Soleimani’s forces were training foreign fighters.

But Mr. Bush had refused, Keane said. Mr. Bush said he thought he would be impeached if he struck inside Iran.

Mr. Graham and Mr. Trump stand together at a campaign rally.Patrick Semansky/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Mr. Graham, who had become a sort of First Friend to the president, said that if Mr. Trump killed Gen. Soleimani, he would have to think about what other steps to take to deter Iran from further escalation. “If they retaliate in some way, which they will, you’ve got to be willing to take out the oil refineries.” Mr. Graham had reminded Mr. Trump for years that oil was the lifeblood of Iran’s economy, the real soft spot. Threaten to take them out of the oil business, Mr. Graham urged. But, he cautioned, if you do, “this will be almost total war!”

The stakes would go up, Mr. Graham said. “You kill him, new game. You go from playing $10 blackjack to $10,000-a-hand blackjack.”

“He deserves it,” Mr. Trump said. “We have all these intercepts showing that Soleimani is planning attacks.”

“Yeah, he’s always been doing that,” Mr. Graham replied. “This is what he does. With the election coming, you’ve got to think about how you respond and how you expect Iran to respond.”

Threatening military action would have to mean a strike in Iran if Mr. Trump wanted to be credible. “That risks major war.”

Mr. Graham had told Mr. Trump earlier in his presidency that Iran’s theocratic rulers “would eat grass before they would give up.” But they could be influenced by economics in addition to ideology.

Financial pressure and sanctions might cause the people to turn on their leaders. Iran was behind both the missile strikes that had killed an American and the militias that had stormed the embassy. “We’re not going to let them get away with this,” Mr. Trump said.

“Mr. President,” Mr. Graham said, “this is over the top. How about hitting someone a level below Gen. Soleimani, which would be much easier for everyone to absorb?” This was a role reversal for Mr. Graham. He was usually the hawk trying to convince a reluctant Mr. Trump to take military action. But a strike on Gen. Soleimani could mean the president was rushing the country into dangerous, uncharted territory.

On the golf course, Mr. Trump tended to focus on the golf. He would drop out of the world, enjoying the endless tinkering with his swing. This week he was changing his grip on his clubs, strengthening it by turning his hands away from the target. He was pleased with the result. His drives landed 10 to 15 yards further, beyond 250 yards.

Later Mick Mulvaney, Trump’s acting chief of staff, made an urgent request of Mr. Graham. Mr. Graham and Mr. Mulvaney had both served in South Carolina’s congressional delegation and knew each other well.

You’ve got to find a way to stop this talk of hitting Gen. Soleimani, Mr. Mulvaney almost begged. Perhaps he’ll listen to you.

Four days later, Mr. Trump ordered the drone strike which killed Gen. Soleimani.

Mr. Trump takes part in a videoconference with members of the military at Mar-a-Lago on Dec. 24, 2019. Bob Woodward would come to the Florida resort a few days later to interview him.Leah Millis/Reuters/Reuters

For his book, Rage, Mr. Woodward would interview the President 18 times, and got access to many top White House officials.Handout/handout

Several hours after Mr. Trump and Mr. Graham’s golf game, I was sitting in the reception area of Mar-a-Lago waiting to interview Mr. Trump – our third interview that month. I had no clue about a potential strike on Gen. Soleimani. I wanted to review with him Robert Mueller’s Russia investigation and Mr. Trump’s impeachment by the Democratic House of Representatives just 12 days earlier. The news, the daily story, was impeachment. Or so it seemed as I watched Mar-a-Lago club members stream in for dinner at what a Secret Service agent called “the regular evening soiree.”

The club, originally built as a private home in 1927, was opulent and luxurious in an Old World way, like a gilded, candle-lit version of the Wizard of Oz’s castle. A 16-inch plaque stood prominently on the receptionist’s table. It read: “Donald J. Trump. The Mar-a-Lago Club. The only six-star private club in the world.”

Suddenly, Trump in suit and tie, appeared with billionaire Nelson Peltz in tow. Mr. Peltz is the 77-year-old founding partner of Trian Fund Management, an investing firm whose portfolio includes holdings in Wendy’s and other prominent brands. Prompted by Mr. Trump, Mr. Peltz said, “Oh, he’s doing great things for the economy. It’s all him!”

Mr. Peltz has a $123 million estate near Mar-a-Lago and saw his net worth increase from $1.4 billion in 2016 to $1.6 billion in 2019-a paper gain of $200 million. He kept pointing at Mr. Trump, repeating, “It’s all him! It’s all him! He did it!”

At one point Mr. Trump pointed to the gold leaf on the 20-foot high ceiling. “Look at that,” he said. “See that? See that?”

Mr. Trump then escorted me back to a private conference room.

We sat next to each other at a large table. Hogan Gidley, his deputy press secretary, sat more than six feet away on the other side of the table, recording the interview on his mobile phone.

We addressed impeachment. Mr. Trump told me he considered himself “a student of history,” adding, “I like learning from the past. Much better than learning from yourself and mistakes.”

Mr. Trump shakes hands with Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan in Davos, Switzerland, on Jan. 21.Jonathan Ernst/Reuters/Reuters

I reached President Trump by phone at 1:45 p.m. on Wednesday, February 19, 2020. He was on Air Force One, flying to Arizona for a rally. The coronavirus was not yet a focus.

What I wanted from the president, I said, “is what was going through your mind as you said what you said or made whatever decision it was on a range of issues in foreign policy, China, North Korea, Russia—”

“Soleimani was a very big event,” Mr. Trump said, referring to his decision to have the head of the Iranian Quds Force killed in a drone strike on January 3. “The head of Pakistan, the prime minister of Pakistan, Khan, said the biggest event of his lifetime. I had no idea. Other people have said the same thing: it was an earth-shattering event.” Mr. Trump and Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan had met privately in Davos on January 21, but I was not able to confirm if Kahn had said what Trump claimed.

Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.