For readers of Hollywood biography, the insidious smear campaign is a familiar plot.

In December, director Peter Jackson claimed that Harvey Weinstein attempted to take his revenge on Ashley Judd and Mira Sorvino, who rejected the movie producer's sexual advances, by blackballing them, characterizing them to his colleagues as "difficult" – that vague but damning catch-all.

Workplace intimidation and sexual harassment are part of Hollywood's tangled cultural legacy, a continuum of sexism that dates back to the early days of talking pictures.

When, in the 1930s, Hollywood's social and economic control was consolidated into a few large studios run by men, it was arguably a de-evolution from the industry's more egalitarian origins. In the first decade of talking pictures, women could talk on screen, but woe betide if they spoke out of turn anywhere else.

In late 1934, studios adopted the Motion Picture Production Code, which was a pre-emptive move engineered to prevent government censorship in the wake of several scandals and the public's subsequent outcry. The Code further denied women professional and personal agency, on screen and off. As an example of the effect it had, look no further than the swift and dramatic shift in top female box office draws between 1934 and 1935 which, according to film historian Jeanine Basinger in her book A Woman's View, shifted from sexually provocative Mae West to innocent Shirley Temple.

The moralizing depictions imposed on film persisted until the demise of the studio system in the 1960s and a New Hollywood was born to bury the old ways.

Now, fresh allegations are coming to light in every corner of the entertainment industry. As we enter what might be considered a golden age of Hollywood reckoning, a new generation of books is challenging accepted history and dismantling Hollywood myth, offering reappraisals of the industry's classic golden age. Some recontextualize misunderstood icons such as Hedy Lamarr or debunk oft-repeated stories frequently underpinned by conjecture and dubious (if any) sourcing, while others restore reputations of female stars such as Miriam Hopkins, long reduced to thumbnail histories.

Her reaction to Bette Davis's Academy Award win, for example, is thus memorialized on TCM's "Trivia and Fun Facts about Jezebel": "Miriam Hopkins celebrated with a temper tantrum during which she trashed the drawing room of her New York apartment."

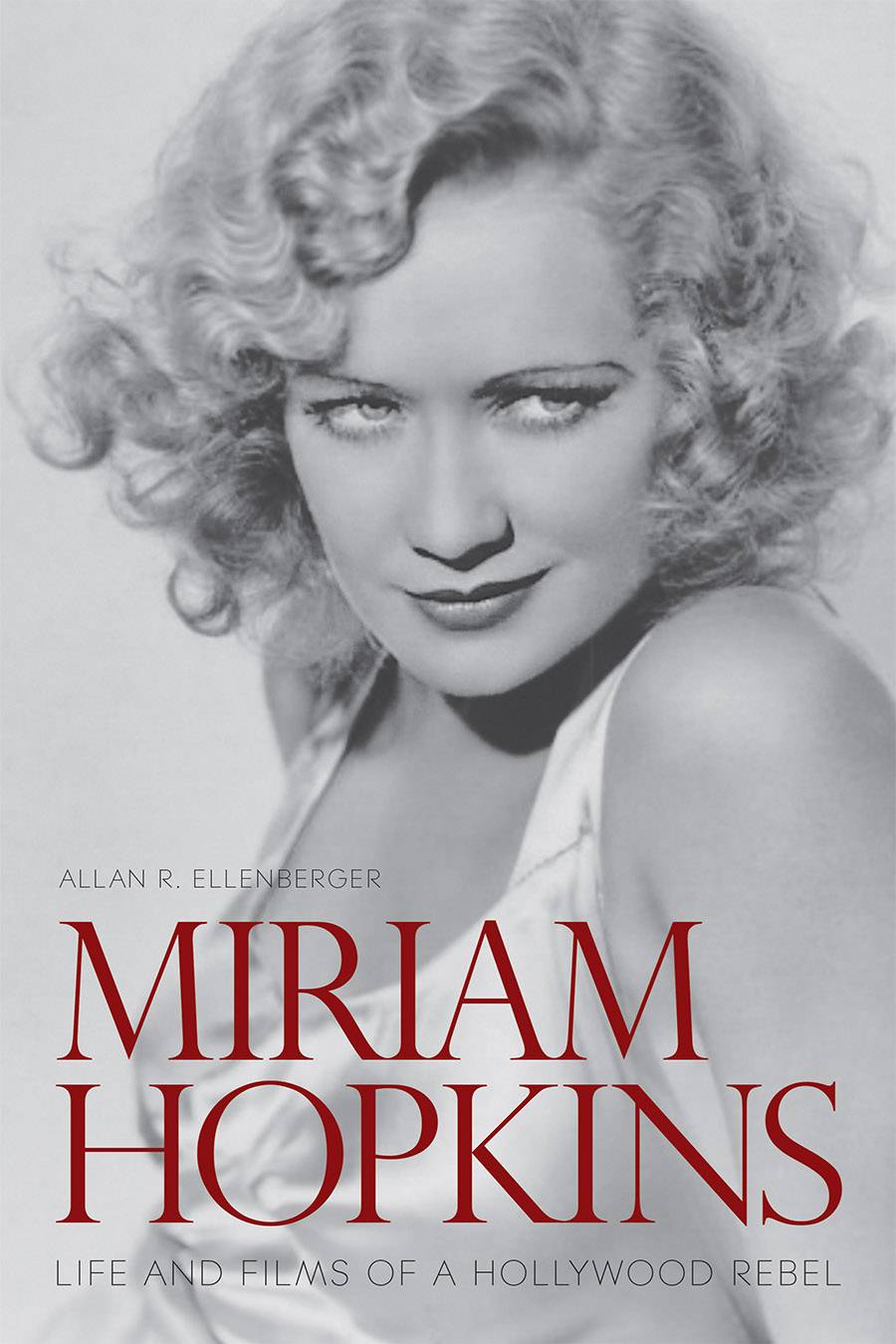

There's no dispute that the incident happened. What isn't included in this shorthand are most of the frustrating facts and surrounding career circumstances that are explored in Miriam Hopkins: Life and Films of a Hollywood Rebel (University Press of Kentucky, 424 pages, $56). For this latest in the publisher's Screen Classics series, Allen Ellenberger spent a decade researching the actor, conducting original interviews with the remaining people who knew her and getting access to her 100-page FBI file. Hopkins is a timely case study of a woman whose ambitious nature was undermined, framed as aggressive, abrasive and difficult. You could read Hopkins as a golden age Cassandra who challenged the patriarchy even when it came to pay equity: Although she was more popular than her Trouble in Paradise co-star Herbert Marshall, for example, Paramount paid her only half his weekly salary, so she went freelance. Yet her reputation as a thrower of tantrums leaves her denigrated and discredited.

In the 1930s, the Broadway actor Hopkins was a gifted comedienne at the height of her popularity. Today, if she's remembered at all, it's for that "difficult" reputation. (To give you an idea: the early manuscript of the Hopkins biography had the working title Magnificent Bitch, which was playwright Tennessee Williams's admiring description of his close friend.) Judged by her performances, she should be as iconic as peers Carole Lombard and Claudette Colbert, but she was less compliant in the studio system.

Hopkins backed and starred in Williams's first produced play and acted in 39 other major theatre productions, and as a result also made fewer films: Just 35 movies, with directors such as William Wyler, Howard Hawks, Michael Curtiz and Rouben Mamoulian – and two with arch-rival Davis. Their now-infamous lifelong feud eclipsed even that of Davis and Joan Crawford depicted in Ryan Murphy's TV series Feud, but was not petty. For one thing, before the two women co-starred together in anything, Davis had an affair with the director Anatole Litvak, to whom Hopkins was married at the time.

Although it's more career chronicle than analysis, Ellenberger's chronology still paints the picture of why Hopkins battled with studio heads or walked out on projects that didn't live up to her creative ambitions. If the thumbnail portrait of the actor were to be believed, it would be a miracle Hopkins got any work at all. That she did – and in as many plum roles as she lost or outright rejected – is a testament to her talent and personal magnetism.

Director Ernst Lubitsch's advice to Hopkins, who openly criticized the Production Code, was to, "Never play 'just nice girls. Always try to get part that are a little off center.'" Her daring parts included the free-thinking third corner of the love triangle of his own ménage à trois screwball comedy Design for Living (and the rape victim in The Story of Temple Drake, based on William Faulkner's provocative novel Sanctuary). Hopkins also starred as Thackeray's anti-heroine Becky Sharp, the titular film role about a cynical and opportunistic social climber that earned her the only Academy Award Best Actress nomination of her career.

In the weeks before Becky Sharp opened, Hopkins appeared on the cover of Time magazine. "Women today might be able to support themselves, and to earn big salaries and hold high positions," she also candidly told Motion Picture magazine while promoting the film, and likened the tactics necessary for a modern woman's survival to those of the 19th century. "But [women] are paid by men, and given positions by men, and it is to men they have to look for everything."

Hopkins attempted to take control of her career, renegotiating her contract with pay cuts in exchange for script, director and co-star approval. Being vocal about the stories and working conditions she wanted is what cost her the lead in the Warner Bros. production of Jezebel – a stage property Hopkins not only partly owned but had originated on Broadway. It instead cemented Davis as the studio's top star. Hopkins's adversarial relationship with studio bosses over her contracts did not stop there. A reputation for combativeness is what shut her out of the part of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind, in spite of the fact she was author Margaret Mitchell's own choice for the part.

Ellenberger's take on Hopkins would be at home in Too Fat, Too Slutty, Too Loud, Anne Helen Petersen's examination of how modern culture demonizes transgressive and unruly modern women (Plume, 288 pages, $16.51), and is a fitting companion to Sass Mouth Dames (Amazon, 166 pages, $9.10), wherein Megan McGurk analyses the cultural impact of a slew of women's pictures from 1929-39.

Women such as Hopkins deserve better than to be demonized by Hollywood – though some, in the case of Hedda Hopper, deserve worse. Variously played by Helen Mirren in Trumbo, Judy Davis in Feud and Tilda Swinton in Hail, Caesar!, Hopper should be a more polarizing figure. But to borrow a line from that last one, would that it were so simple.

Depictions of Hopper fall short of painting a cautionary tale about the complicity and toxicity of her regressive contemporary counterparts such as TMZ. Those recent biopic makeovers of classic Hollywood still have nostalgia on the lens and play down the effects of gossip columnist Hopper's acid malice – and often affectionately employ her comic zingers and famously elaborate hats for comic relief. But not only was Hopper competitive about getting scoops on the personal lives of key industry players, biographers interpret that she pushed a dangerous agenda of political and moral conservatism and mobilized her legion of readers to do the same.

Jennifer Frost's Hedda Hopper's Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism (NYU Press, 304 pages, $40) is a chilling close reading of the infamous columnist's politics. Hopper, a former actor, launched a movie column in 1938 and soon became a powerful figure in the Production Code heyday, when movies dominated mass entertainment and even the private lives of Hollywood stars (particularly its female stars) became the carrier of cultural meaning.

With her column nationally syndicated in 110 newspapers, by the 1950s, Hopper's reach had grown to 32 million daily readers. Frost traces her influence as a powerful tool of white supremacy. As a strident anti-Communist working closely with the FBI and the House of Un-American Activities Committee, she was also an important ally in furthering the Hollywood blacklist. She hampered the civil rights movement by supporting stereotypical and retrograde representations of African-Americans. Frost outlines, for example, how Hopper championed James Baskett and Hattie McDaniel, because of their Uncle Remus and Mammy roles, to further her paternalistic racial agenda.

This sort of excavation and reputational correction is usually the purview of film historians such as Basinger, or niche imprint and academic press biographies. But mainstream titles are now also combining hindsight with insight to dramatize elements of these narratives. In The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, for example, Taylor Jenkins Reid offers an astute and empathetic read about fictional composite of mid-century female stars and the challenges they faced under the oppressive gender bias of the institutional studio system.

In Backwards and in Heels: The Past, Present and Future of Women Working in Film by critic Alicia Malone (Mango, 242 pages, $25), the writer surveys the careers of notable filmmakers dating back to Mary Pickford and influential screenwriter Frances Marion (the first writer to win two Oscars), while in her new novel, The Girls in the Picture (Delacorte, 448 pages, $37), bestselling writer Melanie Benjamin offers a lively fictional take on Pickford's and Marion's creative friendship and how it shaped the early movie business.

In an open letter published in the New York Times on New Year's Day, 300 prominent women in entertainment, from Oprah, Shonda Rhimes and Constance Wu to Ava DuVernay and Reese Witherspoon, launched Time's Up, an ambitious multipronged initiative to combat workplace sexual harassment not just in show business but in low-wage industries. Time's Up also called for female celebrities to adopt another code – an all-black dress code – for the Golden Globe Awards. The red carpet blackout was symbolic as a demonstration of solidarity and protest of an industry that for too long has treated women as ornamental. With a new wave of inspiring books and biographies, it was a welcome reminder that before it turned into an assembly-line glamour factory, Hollywood was pioneered by women who did more than strike poses and smile for the camera.