Latest coverage

- Quebec: Masks will become mandatory in high-school classrooms and team sports will be suspended in COVID-19 “red zones” like Montreal and Quebec City, the province announced Monday after reporting there were 1,423 total cases in the education system, spanning 666 schools.

- Ontario: The Ford government is resisting calls for tougher restrictions in hot spots like Toronto and Ottawa, whose medical officials are pressing Queen’s Park for measures like a shutdown of indoor dining. As of Monday, Ontario had 539 COVID-19 cases in schools, over 335 institutions over all.

Official websites

For the latest information on back-to-school plans, check the provincial and territorial information pages below or consult your local school board. The Public Health Agency of Canada also has its own school guidelines, but they’re not prescriptive, since education is a provincial jurisdiction.

- Atlantic Canada: N.L., N.S., N.B., PEI

- Central Canada: Que., Ont.

- Western Canada: Man., Sask., Alta., B.C.

- Northern territories: NWT, Yukon, Nunavut

How do the provincial plans differ?

A student has her hands sanitized in a schoolyard in in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., on May 11. Quebec was the first province to reopen elementary schools.Christinne Muschi/Reuters/Reuters

Key differences for students

- Attendance: In Quebec – which has the strictest policies for in-class instruction – attendance is mandatory for all elementary and high-school students. The only exceptions occur if a class suffers an outbreak (in which case they’ll be sent home and continue studies there), a student has a doctor’s note saying they’re at high risk of COVID-19, or a student lives with a high-risk individual. Ontario, by contrast, requires school boards to provide remote-learning options for those who want them.

- Masks: Masks in classrooms are mandatory in Ontario for grades 4 to 12, and Quebec is instituting similar rules for high schools as its COVID-19 caseloads increase. Manitoba and Alberta require masks for grades 4-12 in any settings where physical distancing can’t be maintained; Calgary’s two main boards went a step further, requiring masks for all grades, though not necessarily in classrooms. In B.C., Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador, governments made masks for middle- and high-school grades in common areas like halls and buses, but not classrooms; the same is broadly true in Saskatchewan, though there it’s up to school boards, not a provincial mandate.

- Cohorting: Most provinces have created cohorts (B.C. calls them “learning groups”) to limit how many students come in contact with each other. In Quebec, Ontario and Alberta, the cohort is the class itself, though Ontario also capped the size of high-school classrooms in high-risk areas to 15. B.C. allows the largest cohorts: 60 for elementary- and middle-school students, and 120 for high schoolers.

Key differences for teachers and staff

- Masks: Mandatory mask policies will be more common for teachers and other school staff than for their pupils, but the rules aren’t consistent nationwide. They’ll be mandatory in many settings in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador schools. In B.C. and Nova Scotia, masks are optional. In Prince Edward Island, gloves and face shields are strongly recommended if staff are interacting with students with complex medical needs.

- Whose class is whose: To distribute teachers evenly among a larger number of smaller classes, each school will have to create a more complicated schedule than usual, which may involve rotating teachers between classes.

- Indoors vs. outdoors: The federal COVID-19 guidance for schools encourages classes to be moved outside when the weather allows it, and jurisdictions like Nova Scotia plan to follow that advice. But thinking ahead to the winter, when outdoor instruction won’t be as easy, many school boards are pressing for ventilation upgrade that could reduce the airborne spread of the virus: Ontario has pledged $50-million for heating, ventilation and air conditioning improvements.

- Transportation: In some provinces, the most complicated physical-distancing challenges fall to bus drivers, who will have to consider capacity limits (Quebec buses can have no more than 48 passengers) or fixed seating arrangements (Alberta pupils will have to stick to assigned seats). B.C. and Saskatchewan buses may have partitions for drivers. As for masks, they’re required for Manitoba’s bus drivers and encouraged in PEI but not necessarily required everywhere else.

Key differences for parents

- Transportation: The Prairie provinces and PEI are strongly encouraging parents to take their children to school whenever possible, while in other jurisdictions, boards are adding new buses or walk-to-school programs to make physically distanced transportation easier.

- Visiting: Some jurisdictions are limiting access to schools to staff and students only; parents may not be allowed to enter buildings. Instead, there will be designated outdoor pickup areas. Manitoba schools plan to have areas where students who report COVID-19 symptoms can be quarantined before pickup. In Newfoundland, parents of kindergartners may be able to accompany their children on the first day of class, though specific practices may vary from school to school.

COVID-19 notices and inspirational messages cover the front doors of Georgia Avenue Community School in Nanaimo, B.C.Rafal Gerszak/The Globe and Mail/The Globe and Mail

My child is going back to class. What can they do to get ready?

Learn how COVID-19 works

Because closing schools was one of the first steps taken in Canada and abroad when the pandemic was declared, little is known about how children contract or spread COVID-19. Children aren’t invulnerable to the virus, but the good news is that they make up far less of the infection toll than older people, and when they do get sick, their symptoms are often less severe. The bigger risk is that students with mild or absent symptoms will spread COVID-19 to teachers, family members or immunocompromised classmates who are more likely to get seriously ill. To prevent that, it’s essential that children know the COVID-19 symptoms (a dry cough, fever and difficulty breathing) and isolate themselves quickly if they’re not feeling well.

Talk about hygiene

Students at school will be expected to wash their hands a lot more often than usual, and may be given dedicated break times to do so. The video below demonstrates the federal government’s recommended practices for good hand-washing.

Talk about mental health

The pandemic has been a stressful time for everyone, including children who’ve been unable to see their friends or enjoy normal summer activities. But going back to school may give students new and more immediate anxieties to manage. Here are some pointers from parenting coach Sarah Rosensweet on managing children’s anxiety, and a mental-health hub for youth that includes various provincial crisis lines your child can contact if they’re in distress.

Help children stick to a routine

New school routines will be more regimented. They could include staggered lunch and recess breaks to avoid crowding, different lengths to the school day or an alternation between in-class and at-home learning on designated days of the week. Make sure that your child has a day planner or scheduling app, and work with them so they’re getting the right mix of sleep, academics and social time. Here are some pointers on how to do that.

Items to bring

- The old standards: Pencils, pens, paper, scissors and other back-to-school staples are still as necessary as ever, even more so in schools with no-sharing policies to stop the spread of the virus on surfaces. Consider buying a washable pouch to store these items. For more ideas on what to bring, consult this guide.

- Computer: Some jurisdictions, like Nova Scotia, expect students to have their own computers that can be used for remote learning. If an outbreak sends the rest of the class home, this may be students’ only option for continuing lessons. If your child has a laptop or tablet, make sure they’re familiar with the software needed to stay in contact with their class; if they don’t, check with the school board to see if they provide computers or subsidies to buy one.

- Grazeable lunches: Schools may restrict where and for how long children can eat, packed lunches will need to be easy to assemble and carry. Here are pointers from Julie van Rosendaal on good foods to bring.

- Non-medical mask: There are lots of homemade and brand-name masks options to choose from. The trick is finding one that’s the right size for your child and can be worn comfortably for long periods of time. Health reporter Wency Leung talked to medical experts who suggested four things to consider.

Watch how to make three types of masks recommended by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Written instructions are available at tgam.ca/masks.

The Globe and Mail

I don’t want my child back in class. What are my options?

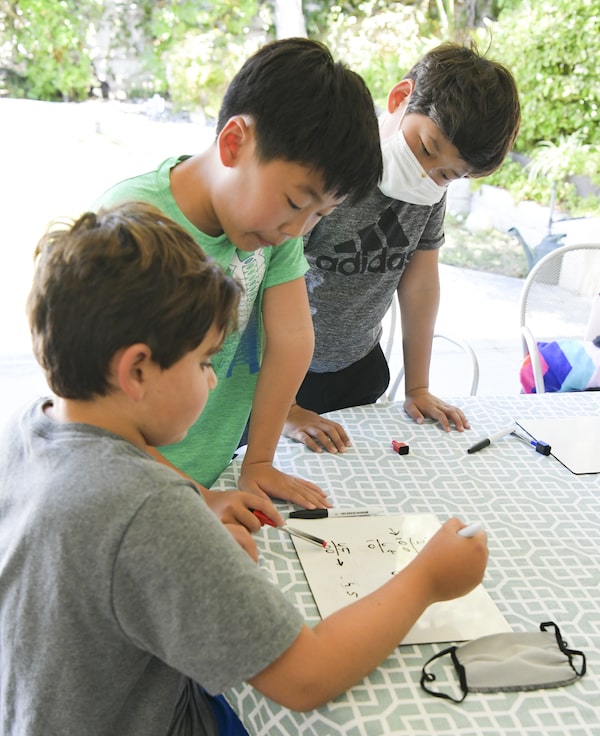

Students work on an assignment in a pandemic learning pod at home in Woodland Hills, Calif., on Aug. 12.Rodin Eckenroth/Getty Images/Getty Images

Virtual studies or home-schooling are still an option in some provinces, notably Ontario, but every family’s situation is different. Ultimately, it’s a question of assessing risk: Is it better to send a child to school and be ready if they get sick, or to keep the child at home and disrupt your family’s working routine? Risk-assessment experts who spoke with The Globe caution that, in a new situation like a pandemic, gut feelings can be less reliable than the advice of experts. But “there’s no right answer as to how that trade-off should go. Everything depends on your own values,” says Paul Slovic, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon.

Some families, skeptical of their local back-to-school plans, have begun organizing “education pods” like those that emerged in the United States over the summer. The idea is to have families pool resources to hire a private teacher to instruct children in small groups. But many education advocates say pods will only segregate privileged families from racialized and low-income ones who will have to face the risks of public education alone. “Wealthy families have the resources to do whatever they want. It’s not a luxury for us parents who have four or five kids,” says Sureya Ibrahim, an Ethiopian-Canadian community organizer in Toronto’s Regent Park neighbourhood.

More reading

Your questions answered

Globe health columnist André Picard and senior editor Nicole MacIntyre discuss the many issues surrounding sending kids back to school. André says moving forward isn't about there being no COVID-19 cases, but limiting their number and severity through distancing, smaller classes, masks and good hygiene.

The Globe and Mail

Education and equity

How race, income and ‘opportunity hoarding’ will shape Canada’s school year

Pandemic-focused school fundraising goals threaten to widen inequalities

Private schools’ health and safety measures spur interest from parents

Commentary and analysis

Naomi Buck: Kids should be back in school – for their sake and for ours. Perfection isn’t necessary

Irvin Studin: Canada needs a temporary Minister of Education

André Picard: Clear back-to-school guidelines are needed to ease parental angst

Compiled by Globe staff

With reports from Wency Leung, Dakshana Bascaramurty, Les Perreaux, Mike Hager, Ian Bailey and The Canadian Press

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.