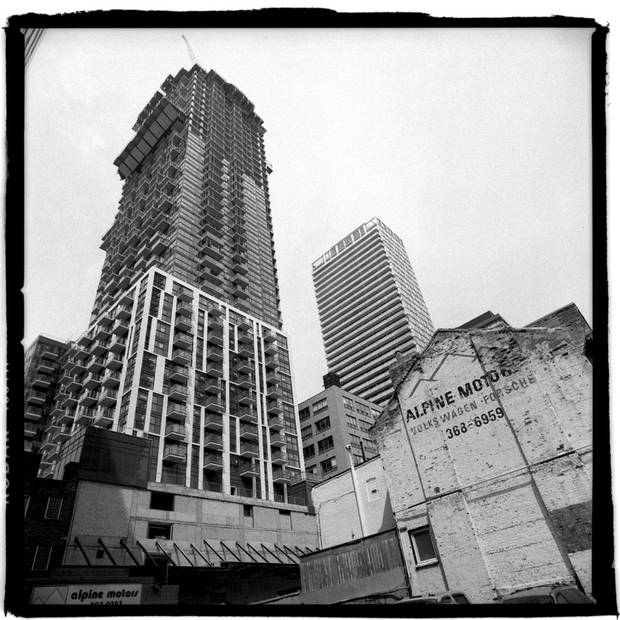

Cities have an endless ability to evolve, to rebound, to reinvent and regenerate themselves, sometimes in ways that would astonish generations past. In their wildest dreams, no one imagined that a rundown Toronto warehouse district could turn into a bristling Shanghai of glass skyscrapers. And yet come to the King-Spadina district, epicentre of the building boom that is transforming the core of Canada's largest city, and behold.

King-Spadina lies just to the west of Toronto's downtown core, flanking Spadina Avenue around its junction with King Street West. The Rogers Centre where the Blue Jays play baseball is to the south, the Art Gallery of Ontario to the north. It is undergoing a high-rise construction boom like Toronto has never seen.

If you stacked all the tall buildings that have already been constructed there one on top of the other they would reach nearly as high as four CN Towers. Another four CN Towers' worth are under construction, 10 in various stages of approval and three on the drawing board. Add that all up, and you get close to 21 CN Towers. Lay all those buildings on their side end to end and they would stretch from City Hall to Highway 401.

No fewer than 99 projects have been built, approved or pitched since 2004. That's one quarter of the total for the entire city and more than the count for two vast suburban districts – Scarborough and Etobicoke – combined. King-Spadina is overtaking even high-rise hubs such as Yonge and Eglinton in midtown Toronto and the Bay and Yonge corridors downtown.

How Toronto deals with the density explosion is at the heart of a big question: Can modern cities become bigger, busier, denser and still be decent places to live? Can you build this much, this high and keep it human? The challenge in King-Spadina is to make sure the district isn't overwhelmed by its own success.

The seemingly overnight explosion of residential development in King-Spadina is part of a broader success story. Toronto has escaped the hollowing-out effect that afflicts many North American cities. About 10,000 people are moving into the downtown area every year, many to live in tall buildings. Toronto has 153 under construction, second only to New York among North American cities, according to one building database. Seven of those buildings are more than 60 storeys, says another source, Skyscraperpage.com, and plans for 15 building towering more than 70 storeys have been proposed.

Unlike the skyscrapers built for the big banks in the nearby financial district, King-Spadina's are mostly towers for living. A development summary for the Entertainment District, which includes King-Spadina, shows more than 1.5 million square metres of residential space being added to the area. That's more than 20,000 new housing units – and 2,443 additional storeys. The number of people who call King-Spadina home is expected to double to 40,000-plus by 2020.

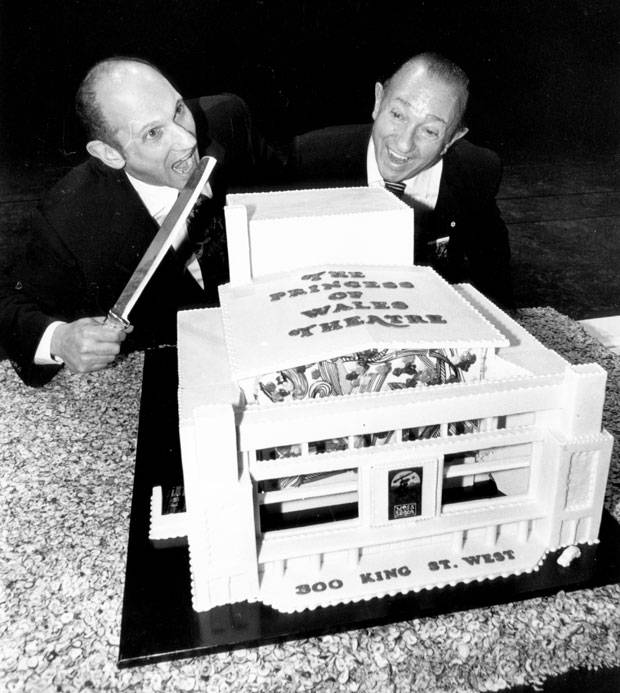

One proposal alone, the Mirvish-Gehry complex, a collaboration of David Mirvish, the theatre impresario, and Frank Gehry, the acclaimed architect, will feature spectacular residential towers of 82 and 92 storeys. On a tour one recent afternoon, local city councillor Joe Cressy passed sign after sign announcing that "a change has been proposed for this site" and showing a drawing of another tower-to-be. On one little block that takes just a couple of minutes to circle on foot, four separate tower projects of more than 50 storeys could soon rise.

"Not only did it happen overnight," he says, "it's literally happening in front of your eyes, because every time you come down here there's another project under construction."

The pattern of high-rise development is driving up land prices, which run from $40-million to $70-million an acre, so developers want to find ways to build to the maximum height possible – and incorporate the highest possible number of units – on tiny lots. In the land rush of the past few years, they have snapped up just about every available site in the district, no matter how small or awkward. Parking lots that once held 20 or 30 cars are seeing towers of 40 and 50 storeys rise on their tiny footprint. On one site on Charlotte Street, a 46-storey tower is proposed on a space smaller than two tennis courts.

With so many old and protected buildings in the area, developers are forced to build behind, around or even over them. One developer wants to create what is in effect a bridge in the sky, using wire, cable and steel to suspend a new building over an existing one.

The intersection of King and Spadina, after 1900.

CITY OF TORONTO ARCHIVES

If the scale of King-Spadina's growth isn't impressive enough, consider what was there before. In the two centuries or so of Toronto's modern history, King-Spadina has been, in turns: a military precinct associated with nearby Fort York; an institutional district that was home to the provincial parliament and Upper Canada College, the famous boys' school; an industrial hub where factories turned out clothing, furniture and machinery; a haven for bohemian artists and other creative types; and an urban club land where the streets came alive after midnight. By the early 1990s, it was a gritty, half-deserted precinct of barren parking lots and slummy warehouses.

What makes the change since then doubly remarkable is that it happened more or less by accident. One tall building, the Festival Tower that rises above the Toronto International Film Festival's Bell Lightbox, became a precedent for another, then another and another. Developers started going to the Ontario Municipal Board, a powerful planning tribunal, to argue that if other towers were rising, theirs should be approved, too. The floodgates opened.

Today, city planners find themselves struggling to keep up with a building boom of a scale and character that no one expected. Mr. Cressy, 33, worked on issues such as AIDS in Africa before he was elected in 2014. Now he spends much of his time negotiating with big developers over such things as the space they must leave between their towers so that residents don't end up staring into each other's bedrooms. "I was doing anti-retroviral treatment for grandmothers until three years ago, so I'm, like, 'Oh, towers? Separation distances? Seriously?'"

Yet he calls King-Spadina the most interesting part of his job. "You're literally deciding what the future of a neighbourhood is going to be. Is it going to be healthy or not? Is it going to be livable or not? Where do I walk my dog? Where is the grass?"

King-Spadina, he argues, needs more parks, community centres, libraries, bike lanes, transit service. The amenities simply haven't kept up with the torrid pace of development. He is so eager to find more open space that he led a move to buy the site of the Hooters restaurant on Adelaide Street for a park. Nicknamed Operation Owl, it failed – the site was too expensive.

Some city leaders share his worries. Jennifer Keesmaat, the city's influential chief planner, has warned about the threat of "hyperdensity" – too much building in one place. But others say the good that has come from King-Spadina's boom far outweighs the bad. Once-sleepy streets throb with life. Scores of restaurants, bars, theatres, shops and other attractions keep the area humming at all hours.

Architects, designers and film and television companies were the first businesses to take over King-Spadina's old factory spaces. Tech firms such as Shopify, the rising Canadian e-commerce firm, have followed, drawn by its urban magic. One developer calls demand for commercial space there "insatiable." The district already has 45,000 office workers. Looked at this way, King-Spadina is an urbanist's dream come true, a place where people live, work and play all in the same district. Urban "intensification" has been a planners' mantra in recent years as they sought to counter years of urban sprawl and create densely populated, walkable communities. The emerging King-Spadina is intensification on Red Bull (a company that naturally has its Canadian offices at the northern edge of King-Spadina, on Queen Street).

David Mirvish says that when his father, "Honest Ed" Mirvish, bought and refurbished the rundown Royal Alexandra Theatre on King in the early 1960s, it looked out on a rail yard across the street. The area around it was "desolate." The change is remarkable. "My father would have loved it. He thought a healthy downtown with many restaurants and stores could be a great place to live."

Many residents, too, relish the area's new vitality, even if they complain about the pace of change. When Valerie Eggertson moved into a Richmond Street condo west of Spadina in 2000, a friend said she would be looking out her window at the drug addicts in the park below. The area was sketchy, but it was all she could afford. Today, she revels in the busy life of the neighbourhood. "To go to TIFF or go to the theatre and walk home, I just love it."

She argues the city simply needs to work harder on making the neighbourhood work. With space so short, where does the pizza delivery vehicle stop without blocking the bike lane? How does an area with so many little apartments accommodate families? She wishes developers would branch out a bit and build more than cookie-cutter glass towers such as the big black one that is proposed near her place.

While many buildings fall into the glass-box-on-a-brick-podium category, a cliché of recent Toronto condo architecture, the district is getting some fresh and creative stuff as well. At Front and Spadina streets, the site of the old Globe and Mail building, developers are starting work on the Well, a mixed-use work-live-shop complex with laneways running through to open it up to people on foot.

Public spaces are improving, too. On John Street, the city is narrowing the roadway to one lane of traffic each way and using the space to put in wider sidewalks, new trees and public art. The intersections are designed to be closed off for street performances during festivals such as TIFF.

On the west side of Spadina, the Waterworks project on Richmond Street will combine condos with a youth centre, a new YMCA, housing for artists, an expanded playground and a big food hall.

To save cultural spaces such as artists' and dancers' studios that are being priced out of the district, the city is using the fees collected from developers to build new spaces – or striking deals with them to include theatres and art galleries. One project, the two-tower King Blue, will include a new home for Theatre Museum Canada, one of several big new cultural venues coming to the area.

As for transit, the city is about to experiment with a special transit corridor on King Street, limiting automobile traffic to clear the way for the crowded, often painfully slow, King streetcar.

Resident Nicole Mantini, a 33-year-old lawyer, says King-Spadina has changed a lot since she moved there in 2009, when singles and young couples were predominant. Now, "you see people out for Sunday brunch with babies and strollers."

That heralds yet another unlikely transformation for this dynamic quarter of an ever-changing city. Mr. Cressy likes to say that in many ways the city of Toronto began in King-Spadina, it grew up in King-Spadina, and, now, much of its future will take shape in King-Spadina.

BUILDING TORONTO: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL