Test Article - waypoints

EIGHT SECONDS

The life and death

of a cowboy

When Canadian bull rider Ty Pozzobon killed himself in January he turned a spotlight on the world’s most dangerous sport. Only 25 years old, he was a son and brother, a newlywed, and a star on the rise. He would also become bull riding’s first confirmed case of CTE. Among the factors that led to his suicide: concussions too numerous to count, stubbornness among cowboys to acknowledge the dangers of head trauma, and lack of consistent and fitting medical oversight to protect bull riders from themselves and the near-ton animals they compete against

Marty Klinkenberg spent the summer with Pozzobon’s closest colleagues on the professional bull-riding tour to explain how a way of life in the West threatens the health and safety of men who do it for love, and how the young cowboy from Merritt, B.C., could be the catalyst for change the sport desperately needs

Chapter 1

In the six months before he killed himself, Ty Pozzobon was the best bull rider in Canada. Over the summer of 2016, he won more events than he had in the previous five years. He was so good he earned $100,000 at the world championships, the biggest prize of his career.

At the same time, he began pulling away from friends. His marriage, barely a year old, was in trouble. He had been knocked unconscious while riding bulls at least 13 times. Though he didn’t know it, he was afflicted with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), the degenerative neurological disease that claims the lives of hockey tough guys and football players who suffer too many blows to the head. He was having balance issues and could not eat. He could not sleep and had trouble remembering things. He talked about being sad, and not knowing what he was going to do with his life. He was anxious and angry.

“In that last year, some of the things he was doing were uncharacteristic, and they brought out an uncharacteristic side in me, too,” says Jayd Pozzobon, left a widow at 25 years old. “I was hurt and shocked and didn’t understand what was going on.

“I think even he didn’t know how bad it was.”

She was training barrel-racing horses in Stephenville, Tex., in April of 2012 when they met. They were introduced by one of his buddies, a fellow bull rider. Within two weeks, they were a couple.

“When I met Ty, it was the most whole I felt in my entire life,” Jayd says, voice trembling. “I told him, ‘I don’t care where you take me or what we do, as long as I have you.’

“There is not a single person that met him that didn’t absolutely fall in love with him. He had the best heart, and most giving and positive soul.”

Her mom is a barrel racer and her dad is a former bull rider who raises bucking bulls. Her grandmother rode a bull, just once, to prove women could do it.

Jayd’s parents divorced when she was 17. She moved out of her mother’s house in Gonzales, Tex., the day after high school. After Ty took his own life on Jan. 9, 2017, she moved back in.

Her Instagram scroll shows pictures of the widow and her cowboy. In one, their hands are clasped as she shows off an engagement ring. In another, Ty sleeps with his arms wrapped around the Great Pyrenees puppy she received as a gift at her bridal shower.

They married on a friend’s ranch near Gonzales on Oct. 11, 2015. He wore a light beige cowboy hat and a bow tie. She wore a pretty white dress and carried wildflowers. Their first dance was Stand By Me. He was still on the mend from a broken femur suffered riding a bull a month earlier.

After their wedding, Jayd moved from Texas to British Columbia. They lived outside Merritt, up a mountainside from Ty’s parents. Soon, they began having problems.

“A lot of guilt runs through your mind and your heart, thinking, ‘Did I cause this, or what could I have done different?’” Jayd says. “I would say, ‘We are working on our marriage and you just had the best year of your career. You have the best family in the world and everybody loves you so much. What’s wrong?’”

He couldn’t explain it.

“It was not his fault,” she says. “I think there was a reason for his behaviour. Brain injuries played a major role.”

IRRATIONAL PASSION

He suffered one concussion after another over the five years they were together. The worst occurred in Saskatoon on Nov. 14, 2014.

That night, Pozzobon was thrown off at the end of a ride aboard a hulking black bovine named Boot Strap Bill. The 5-foot-9, 135-pound cowboy was already unconscious as he flew through the air. When he landed, the bull, 12 times Ty’s weight, stomped on his helmet and split it in two. Then, as he lay on his stomach with his face to one side in the dirt, Boot Strap Bill’s hoof came down on the back of his skull.

He didn’t come to for 24 minutes.

“I will never forget it,” says Ted Stovin, a former bull rider who served as a groomsman at Pozzobon’s wedding and attended his funeral 15 months apart. “It scared the hell out of all of us. I thought he was dead.”

Ty’s mother, Leanne, has never watched the video. His dad, Luke, watched once. Luke rode bulls professionally, but stopped when he and Leanne were married in March of 1990.

Father and son shared the same passion. They raised bucking bulls together, and Ty would call his dad after every ride. That night, Ty did not call. Leanne learned he had been hurt when she saw it mentioned online.

“I was frantic,” she says. “I kept phoning. He didn’t pick up.”

When Leanne finally reached him, he slurred words. He was taken to the hospital, but released after a few hours.

“He couldn’t even talk properly,” Leanne says.

In Texas, Jayd got a call that Ty had a serious concussion.

“As sad as it is, I was used to him being knocked out,” she says. “I was ignorant to the facts of what I was dealing with. I thought if he was conscious, everything was fine.”

The next morning, Ty called Jayd from a taxi. He could not remember where he was going. The driver told her Ty asked to be taken to the airport. Jayd told him not to board a plane. A family friend was dispatched to pick him up. Ty was taken to the home of his best friend, Tanner Byrne, in Prince Albert.

When she arrived that night, Jayd realized something was wrong. Ty fumbled words. At one point, he got lost between Tanner’s house and his in-laws’ place. They live 20 steps apart.

“He had good days and bad days, but he was never the same after that,” she says. “I don’t think you recover after a huge brain injury like he had.”

Pozzobon took almost four months off. He saw a neurologist in Connecticut. He scored below average on every test. The doctor sent him home with a letter. It suggested that he find a new profession.

“Deep down, I think he knew he had to stop bull riding, but passion is irrational,” Jayd says. “He lived it, ate it and even dreamed about it.”

Once, she found him taking a bull-riding pose in his sleep.

He resumed riding in February of 2015 on a limited basis. The 13 events in which he competed were the fewest in any year.

“After Saskatoon, I begged him to stop,” Jayd says. “I told him, ‘I will do anything you want if you quit.’”

The first time he got on a bull after that, she threw up.

“I remember thinking, ‘How can I be supportive and realistic at the same time?’”

Pozzobon returned to the circuit full-time in 2016. He won more than $160,000 and had his best year as the PBR Canadian champion. He was the only participant to have four successful rides in a row in Las Vegas. Thrown off in his last two attempts on the final day, he finished fourth in the world standings.

He and Jayd spent Christmas with his family, and worked on their relationship. He killed himself in British Columbia several weeks later. He died from carbon monoxide poisoning.

“The timing was odd,” Jayd says. “He had no reason to do this if there was not something wrong internally. I definitely didn’t see it coming.”

Leanne took him to a doctor on Dec. 19. She was growing more and more concerned.

“I tried to get him help,” she says. “I knew him better than anyone. He wasn’t himself. But I never thought he would do that.”

She remembers him being joyful as a kid.

“He always loved to please everyone,” she says.

On Jan. 9, he did not respond immediately, as always, when Leanne texted him. After five minutes, she knew something had happened. He was unresponsive when she found him near his home. He died as paramedics tried to revive him. He was 25.

The last text message Jayd had received from him said, “I love you baby. I can’t wait to be in your arms again.”

Chapter 2

It is a cold, snowy March night in Lethbridge, Alta. Bull riders file into a darkened arena. A fire is lit around them, illuminating the shape of a heart.

A crowd watches a tribute video to Ty Pozzobon. When it ends, a spotlight falls on Brett Gardiner. He sits alone on a stage.

“The bull riding world has lost one of its very best,” says Gardiner, an announcer on the Professional Bull Riders circuit. His voice cracks. “He loved the way of life and embodied what it was. He was the true definition of a cowboy.”

It is the first major event in Canada since Pozzobon’s death. Riders wear Pozzy patches on their hats. Vendors sell T-shirts to raise money for the Ty Pozzobon Foundation.

Tanner Byrne and Chad Besplug started the organization to educate rodeo cowboys and bull riders about concussions a month after Ty died. They were his closest friends on the circuit.

“We want to break the stigma and start the conversation about mental health,” says Besplug, a two-time Canadian champion. He announced his retirement after Ty killed himself.

In each of his last three rides, Besplug sustained concussions.

“Riding a bull while you have a head injury doesn’t show how tough you are, it is just plain dumb,” he says. “It doesn’t heal like a broken bone. The damage sticks with you forever.”

Pozzobon’s reluctance to stop competing even as his health deteriorated is not uncommon. A cultural treasure in the Canadian and American west, bull riding has been forced to acknowledge its quiet concussion crisis.

Cowboys live for eight seconds aboard the 1,800-pound animals that sometimes want to kill them. The danger is the allure.

“The guys that do this love it despite the risks,” Besplug says. “That’s what makes it such a beautiful sport. If it wasn’t like that, anyone could do it.

“If it was still in my heart, I would lie to my wife and family and every doctor so I could ride.”

He felt for a long time that Ty would have problems caused by concussions.

“I didn’t think it would happen so soon,” he says. “I have guilt because of it, and I think a lot of people feel that way now.

“We realize this tragedy gives us a huge opportunity. Most people don’t get this chance. We can’t fuck it up.”

TOUGHEST ATHLETES

Bulls kick and spin and lunge as the season-opener begins. Riders struggle to stay on for the required eight seconds.

One hand grips a rope lashed to a bull, the other whips through the air as the animal erupts. If the free hand touches the bull, the cowboy is disqualified.

A whirling beast named Darkness tosses Shay Marks in a heartbeat, then returns to its pen, hind legs kicking in the air. General Defence flings Tim Lipsett as easily as a cow chip, then nudges him with its nose as he lays on the dirt.

Some bulls take victory laps, dripping snot and drool. One chases Ty Prescott and hooks him in the butt with its horns. He is a bullfighter, one of the guys whose job is to keep the animals away from riders once they have been thrown off.

“Any bull fighter that tells you they aren’t scared is either crazy or lying to you,” Prescott says. “You never know when your ticket is going to get punched.”

Cowboys have a reputation as tough athletes. Bull riders raise the bar. They separate shoulders, break ankles, fracture arms and tear muscles off the bone. They compete with jarring injuries, jamming broken feet into cowboy boots, bleeding openly. In a rodeo dressing room, ice packs and slings are as common as chaps and spurs.

“He was passionate about bull riding,” Ty’s father, Luke, says. “It was his way of life. He would tell me, ‘I don’t know how to do anything else.’”

Concussions are frequent, hard to count and easier to hide. And riders do. They pay to enter, and prize money is hard to come by. They scrape out a living eight seconds at a time, and take unholy risks.

Getting past cowboys’ reluctance to admit their vulnerability concerns Tanner Girletz, the son of a five-time national champion.

“All I know is that I didn’t feel too fucking tough when I was carrying my friend in a casket,” he says.

The Professional Bull Riders was founded in 1992 by 20 cowboys who donated $1,000 each and broke away from rodeo to make it a stand-alone sport. The PBR has circuits in Canada and the United States, with its American Built Ford Tough Series the most elite. Its final event, the PBR World Cup, takes place at Rogers Place in Edmonton beginning on Nov. 9.

At the same time, the Canadian Professional Rodeo Association will hold its national championship at the Northlands Arena. For a week, Edmonton will be bull riding mecca. More than $2.5-million in prize money will be handed out.

When he was a rookie, Ty’s friends played a trick on him. The day before the Canadian Finals Rodeo, they told him it was cancelled.

“It really got him going,” says Scott Schiffner, bull riding’s version of Sidney Crosby. The face of the sport in Canada, he gave a demonstration to Will and Kate during a royal visit, and accompanied Stephen Harper on a trade mission to China. “It was the first time I ever saw a guy cry about not being able to go to a rodeo.”

When the show is over in Lethbridge, Tyler Thomson loads horses onto a trailer. His job is to rope bulls after a ride. Often, they are stubborn to return to their pens.

Ty Pozzobon stayed with Thomson’s family last summer. Thomson remembers watching him walk beside his four-year-old, clutching her hand.

“My little girl loved him,” the two-time Canadian bull riding champion says. “I jokingly say he was Harlow’s first boyfriend. She still sings songs about him every day.”

Chapter 3

In May of 2012, Ty Pozzobon got a concussion in Nampa, Idaho. Bucked off a bull named Chocolate Thunder, he landed on his head.

Less than a year later, he was knocked unconscious in Louisville, Ky. As he was thrown off Carolina Kicker, Pozzobon banged the back of his head against its horns.

Early in 2014, he was knocked out months apart. The second time was a vicious wreck in Fresno, Calif., on a long-horned bull named Coyote. The grandson of a bull that competed seven times at the PBR world championships, Coyote was known to chase riders down.

That night, Pozzobon ended up beneath him. Coyote trampled his helmet, face mask, collarbone and chest.

The young cowboy was carried out of the arena on a backboard, but was soon sitting up and talking. He did not go to the hospital, and the next day complained only that he was tired and had sore ribs.

“The head is the only thing I worry about,” he told a communications officer on the PBR tour. “A broken arm or something like that will heal on its own.”

Five months later, in Saskatoon, Boot Strap Bill cracked Pozzobon’s helmet in half and kicked him in the back of the head.

“I think a lot of people were in denial about how many concussions he had, or maybe he just did a good job of convincing people he was okay,” Jayd Pozzobon says. “You can see signs here and there, but you don’t really know how bad it is unless you are that soul living in a body that has withstood trauma.”

As a little boy on the family ranch in south-central British Columbia, Ty rode a wooden horse around the house. At 5, he stared at steers through the fence and rubbed his hands together with excitement. After his parents taught him to rope cattle, he lassoed them and rode them – facing backward – with his kid sister, Amy, taking video. His father worried their horns were so sharp that he covered them with tennis balls.

To hone his technique, Ty rigged up an apparatus that heaved and lurched like a bull.

By the time he was 15, he was beating adults at amateur rodeos. He won a national high school championship in 2009, and was the Canadian Professional Rodeo Association’s top rookie the following year. He qualified for the Canadian Finals Rodeo three times, and competed at the Professional Bull Riders world championships four of the past five years.

In 2016 in Las Vegas, he rode the whole week with a broken hand.

“He was a gritty sucker,” Chad Besplug says. “He would never quit.”

HIDDEN HEAD TRAUMA

Bull riders are independent contractors in Canada and the United States. In Canada, they compete on a handful of circuits. During the summer, some enter three or four rodeos a week to earn a living. Organizers expect riders to admit it if they have symptoms of a concussion.

“Have you ever played poker with a cowboy?” Dale Butterwick says. “They all have poker faces.”

Butterwick was head athletic trainer at the University of Calgary in the early 1990s when he accompanied a friend to the Calgary Stampede and was alarmed by what he saw. He joined a group called the Canadian Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team.

He and other members created a medical protocol for Canadian rodeos using their own information and by adopting guidelines from other sports. In Calgary in 2004, they presided over the first international rodeo-medicine conference.

Butterwick and 70 other health-care professionals and doctors from across North America created a plan to treat concussions. A bull rider should sit out a week when concussed, and pass an exercise test before returning.

It was hoped the recommendations would be adopted by major rodeo groups. Thirteen years later, the standard has not been endorsed widely. In Canada, the Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team can suggest a cowboy is unfit to ride, but beyond that, it lacks authority.

“In other sports, a doctor can tell an athlete, ‘You can’t play’ and they don’t,” says Butterwick, the chief athletic therapist for Canada’s medical team at the 1988 and 1996 Olympics. “In rodeo, there is no team physician.

“To be a skeptic, they just hope a guy is okay when he returns.”

It is impossible to know how often Pozzobon competed when he should not have.

MRIs revealed that he had bleeding within his brain 20 times. After his death, Leanne discovered records that detailed concussions she never knew about, as early as when he was 17.

One time, he couldn’t see out of his left eye for several hours.

“With Ty, every time he rode there was so much effort, it caused maximum risk,” Besplug says. “He pushed himself hard.”

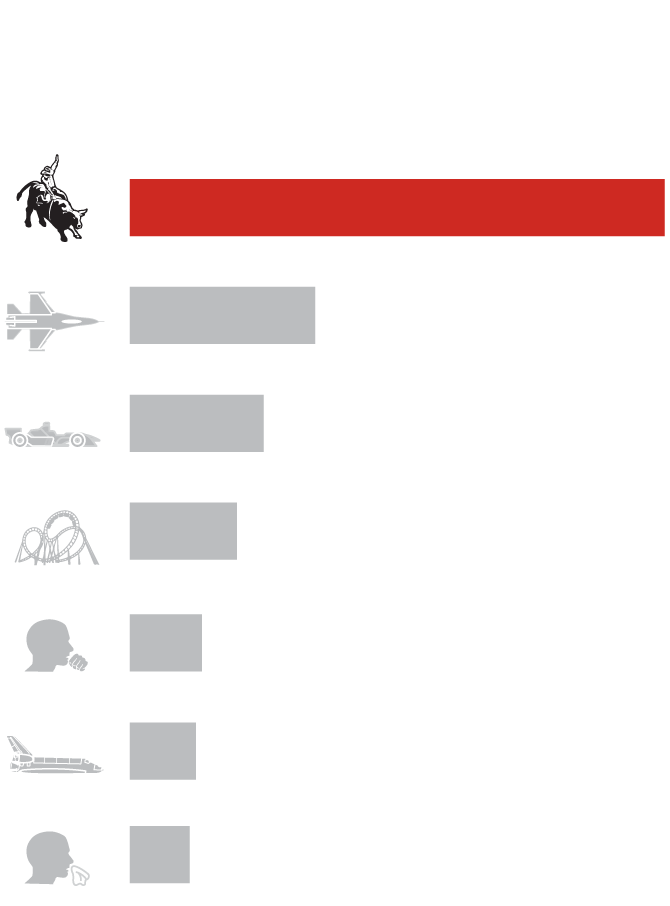

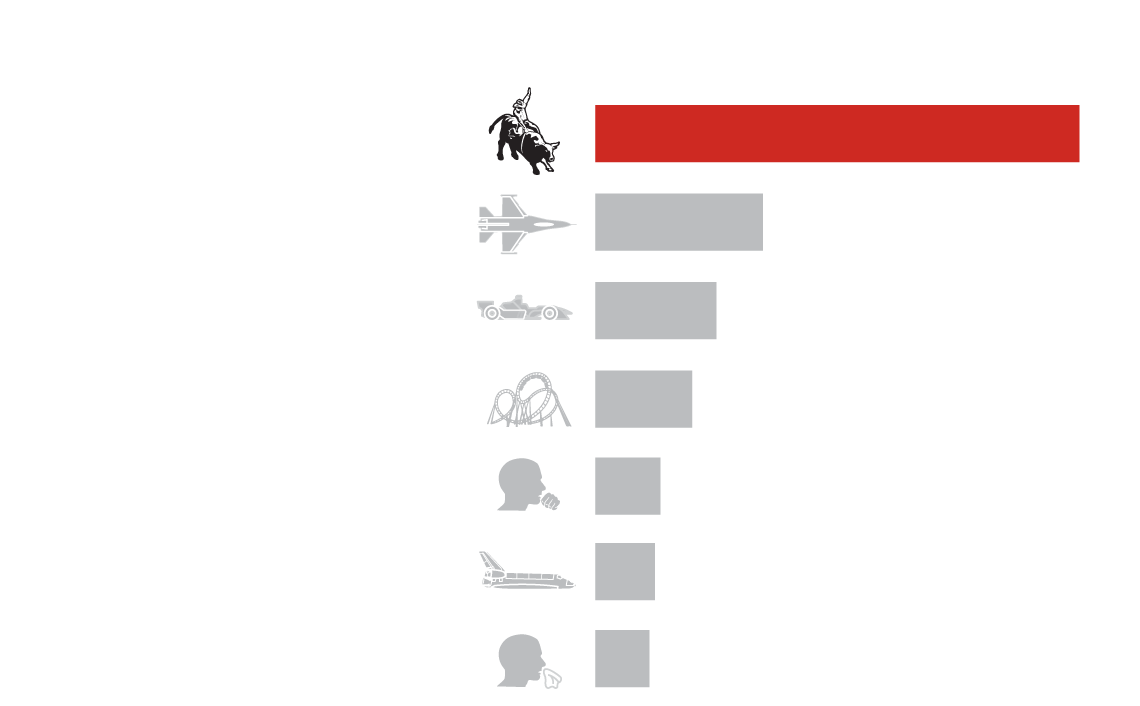

Bull riders suffer concussions when they fall, but can be injured during a successful ride. Some black out from gravitational forces when pitched sideways and whipped back and forth. In fractions of seconds, riders can experience a G-force as high as 26, more than fighter pilots and astronauts.

Over the course of an eight-second ride, bull riders can face up to 26 Gs, almost three times the amount felt by an F-16 pilot.

Bull ride

Up to 26 G

The F-16 Fighting Falcon

9 G

Formula One car, peak lateral in turns

6.5 G

Mindbender Roller Coaster, Alberta

5.2 G

Cough

3.5 G

Astronauts at launch

3.2 G

Sneeze

2.9 G

Over the course of an eight-second ride, bull riders can face up to 26 Gs, almost three times the amount felt by an F-16 pilot.

Bull ride

Up to 26 G

The F-16 Fighting Falcon

9 G

Formula One car, peak lateral in turns

6.5 G

Mindbender Roller Coaster, Alberta

5.2 G

Cough

3.5 G

Astronauts at launch

3.2 G

Sneeze

2.9 G

Over the course of an eight-second ride, bull riders can face up to 26 Gs, almost three times the amount felt by an F-16 pilot.

Bull ride

Up to 26 G

The F-16 Fighting Falcon

9 G

Formula One car, peak lateral in turns

6.5 G

5.2 G

Mindbender Roller Coaster, Alberta

Cough

3.5 G

3.2 G

Astronauts at launch

Sneeze

2.9 G

This year in Tucson the PBR began testing technology to make scoring more precise. Sensors placed on bulls collected data on speed, spin, thrust, height and direction to measure the difficulty of a ride. One had a G-force of 18. The average ride measured 12 Gs.

A handful of studies over the past 25 years agree that bull riding is dangerous and the head and brain are especially vulnerable.

Through his work with the Canadian Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team, Butterwick helped conduct extensive research on bull riding. In 2007, the subsequent report identified it as the world’s most dangerous organized sport. The injury rate for bull riders was found to be 13 times greater than hockey players and 10 times higher than football players.

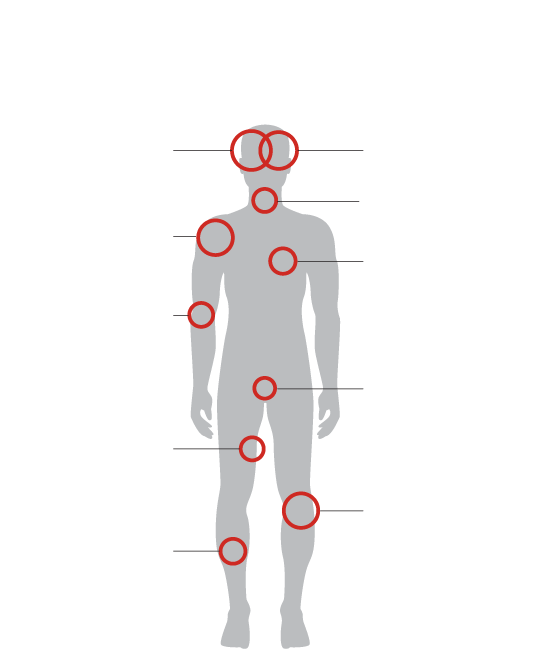

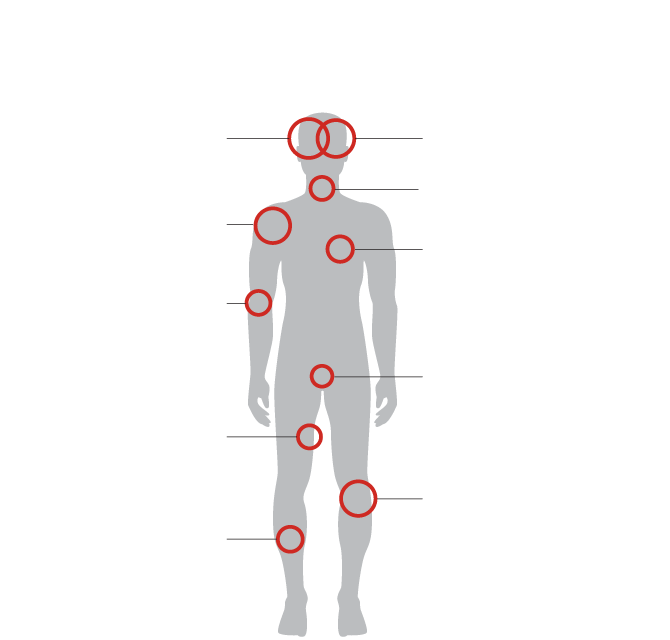

A 2011-14 study by the Justin Sportsmedicine Team, a program based in Texas, found bull riding accounted for 44 per cent of all injuries at major rodeos throughout the United States. The head and brain suffered most, accounting for 22.7 per cent of injuries. Most are caused by contact with the animal.

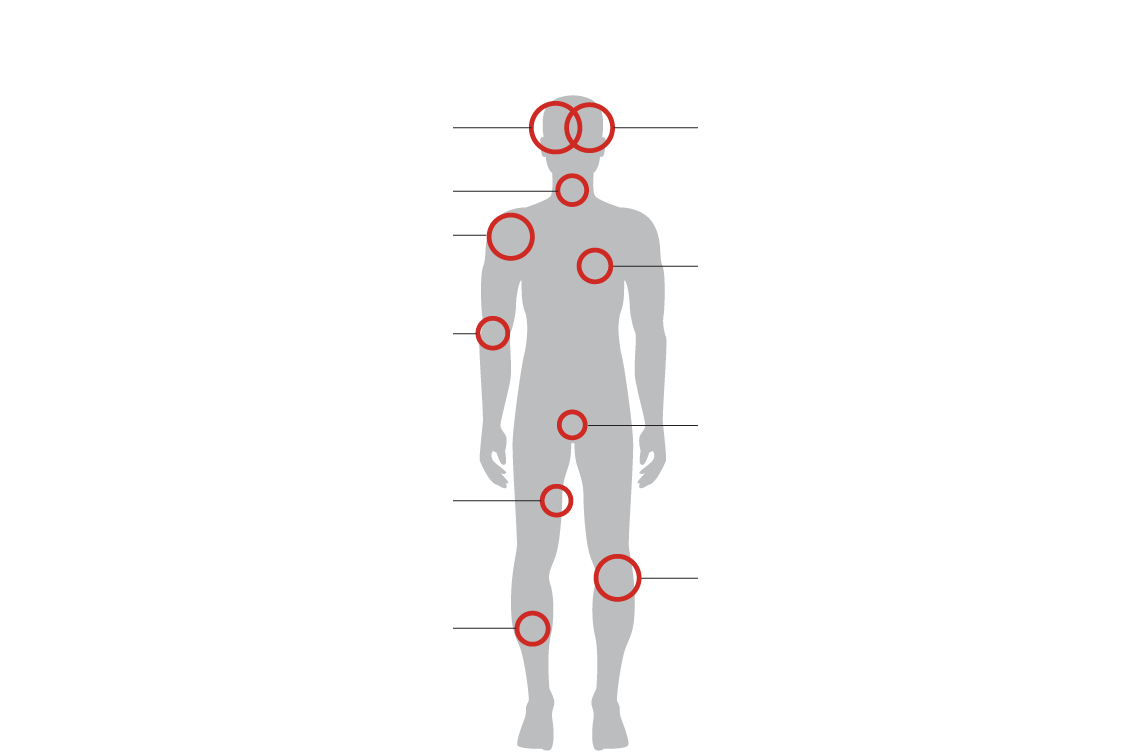

Body parts most often injured bull riding

2011 - 2014

Neurological

system (includes

brain):

Head:

12%

10.7%

4%

Neck:

Shoulder joint:

9.5%

5.1%

Chest:

Elbow:

Pelvic girdle

(including

gluteal muscles):

4.5%

3.4%

Adductors:

4.2%

Knee:

9.4%

Lower leg:

4.9%

Body parts most often injured bull riding

2011 - 2014

Neurological system

(includes brain):

12%

10.7%

Head:

4%

Neck:

Shoulder joint:

9.5%

5.1%

Chest:

Elbow:

Pelvic girdle

(including

gluteal muscles):

4.5%

3.4%

Adductors:

4.2%

Knee:

9.4%

Lower leg:

4.9%

Body parts most often injured bull riding

2011 - 2014

Neurological system

(includes brain):

10.7%

12%

Head:

4%

Neck:

9.5%

Chest:

Shoulder joint:

5.1%

Elbow:

4.5%

Pelvic girdle (including

gluteal muscles):

3.4%

Adductors:

4.2%

Knee:

9.4%

Lower leg:

4.9%

An extensive study between 1981 and 2005 by Mobile Sports Medicine Systems in Texas found head injuries were most frequent and had increased since 2000, in part because bulls have been bred bigger.

In the United States, the Professional Bull Riders has protocols for concussions on its Built Ford Tough Series. Only the top 35 riders in the world compete. Medical staff sees most of the same cowboys every week. Each is required to pass a concussion test at the start of the season, and is re-tested if one occurs.

“Bull riding is a sport where 160-pound guys and 1,600-pound bulls are adversaries,” says Dr. Tandy Freeman, medical director of the tour and the Justin Sportsmedicine Team. He is an orthopedic surgeon, and for five years served as a team doctor for the Dallas Mavericks. “The guys are overmatched physically to a degree you don’t see in other sports.”

Freeman attends PBR events in the United States. He says no test diagnoses a concussion with 100-per-cent accuracy. The exams he and his staff administer identify symptoms.

“As one would expect in other sports, some bull riders can be reluctant to take themselves out of competition,” he says. “Those are the guys that come in and say they are not symptomatic when they are. The testing we do is designed to catch them.”

In Canada, PBR riders compete on other tours, making it difficult to maintain a universal testing program.

“We have no control with what happens when riders are at events other than ours,” Freeman says.

Butterwick wants all rodeo organizations to adopt strict guidelines. There are nearly 2,100 professional bull riders, almost as many athletes as in the NFL and NHL combined.

The Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, which stages more than 600 events in the United States, has no written protocol for concussions. On-site care is controlled by each individual rodeo committee. The Canadian Professional Rodeo Association, which co-sponsors events with the PRCA, relies on the expertise of the Canadian Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team.

“The whole industry needs to come together,” Butterwick says. “It seems like the rodeo world is afraid somebody is going to get mad if they do something.

“The time for action is well past.”

HELMETS VS. HATS

On a Saturday night in July, Brandon Thome and other members of the Canadian Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team arrive two hours before the start of the final round of the K-Days Rodeo in Edmonton. Thome is an athletic therapist. The team includes chiropractors, massage therapists and orthopedic surgeons. There is no doctor at events. Cowboys with serious injuries are sent to a hospital.

The not-for-profit rodeo-medicine team is paid from the cowboys’ annual dues and entrance fees. In the aftermath of Pozzobon’s death, it was booked at 60 rodeos and bull-riding events in Canada this year, up from 21 in 2016. The team has developed its own concussion protocol that follows the NHL’s policy and is working with rodeo organizations in hope of implementing it.

Thome and his colleagues confer with cowboys before and after they perform. They help them stretch, apply tape and give them ice baths. They suggest exercises to soothe aches and pains, but rely on riders to tell them if they suspect they have been concussed.

Thome wants the power to pull them from competition, and believes a doctor should always be on hand.

“Everybody agrees how important it is to have proper medical staff,” he says. “It is how to get the proper people there and who pays for it that is the issue.”

It is not certain if tighter scrutiny or stricter protocols would have prevented Pozzobon’s death. He wore a helmet because he thought it would prolong his career.

Cowboys born on or after Oct. 15, 1994 must wear a helmet at PBR events.

Scott Schiffner, who was an usher at Ty Pozzobon’s funeral, has ridden nearly 1,000 bulls since turning pro in 2003. He prefers a cowboy hat to a helmet.

“Some guys put them on and act bulletproof,” Schiffner, 37, says. “They think they are invincible.”

In 2015, Schiffner sat out the championship round of the Canadian Finals Rodeo because of a concussion. By failing to place, he did not qualify for the Calgary Stampede the following year.

He says some riders with concussions won’t risk their earnings and points.

“Guys in the NHL make a million-plus a year whether they are injured or not,” Schiffner says. “We don’t. Until we are guaranteed money, there are guys who are not going to be 100-per-cent truthful.”

Even with helmets, Dr. Bennet Omalu says bull riding is unsafe. The forensic pathologist, who discovered CTE in former Pittsburgh Steeler Mike Webster in 2002, says all contact sports are too dangerous, especially for children.

CTE is found in athletes and others with a history of repeated concussions and brain trauma. It can only be diagnosed through an autopsy. Symptoms include impulse-control problems, aggression, anxiety and depression. Some victims are driven to suicide.

Not unlike other athletes, bull riders start when they are young.

“We need to look at this as a public-health issue,” Omalu says. “We should not let parents expose children to harmful factors.”

In January, Ty Pozzobon’s funeral snarled traffic on the main street of his hometown in British Columbia.

Leanne and Luke wore Ty’s PBR jackets as they led the procession into the civic centre. The cowboys wore black hats.

Chapter 4

The northernmost bull-riding event in North America occurs each June in Wanham, Alta. The hamlet of 125 people is an hour from the Alaskan Highway.

For 19 years, the Professional Bull Riders have held an event along with Wanham’s annual horse-plowing matches. Bull riding is staged in an 80-foot by 90-foot ring set up in a pasture. Ladies from a seniors centre sell pies.

“This is as grass roots as it gets,” says Jason Davidson, the show’s producer.

There are 1,600 people in Birch Hills County. On this night, all but about 100 turn out.

Before the show, bulls in pens stomp and throw clumps of dirt. Some roll in the mud. One threatens to charge when a spectator tries to take a picture.

Riders arrive an hour early and congregate behind the grandstand. Most have driven nine hours from Calgary, the site of a PBR program two nights earlier. They drive to all but a handful of events. Dakota Buttar, a rider from Saskatchewan who competes in Canada and the United States, put 103,000 kilometres on a new truck last year.

More than competitors, the cowboys are a family.

“It was never just the four of us at home,” Leanne says. “There were four boys sleeping in Ty’s room for two years.”

Bull riders are more like brothers than rivals. They root for one another, travel together, and at times sleep side by side.

Two nights before Ty died, Chad Besplug spent the night. They lay in bed together watching bull-riding videos.

Ty was so close to his mother that fellow bull riders poked fun, calling him a momma’s boy.

“To shut us up, he would say, ‘I’m sorry that my mother loves me so much’,” Besplug says.

In July of 2016, Ty Prescott made a confession to Pozzobon.

“We were sitting around my house drinking beer and talking about our lives,” says Prescott, one of the best bull fighters in the business. “I told him I had been using crystal meth for three years.”

They had met in 2008 at a rodeo in Alberta. They bought bulls and swapped them back and forth. They talked four or five times a day.

Pozzobon hounded him to quit. He had his back the same way Prescott had his in the arena.

Prescott promised him he would stop in the new year. In January, when he learned Pozzobon was dead, he fell apart.

In the ring, he wears a belt buckle that Pozzobon won one year at the Canadian Finals Rodeo. He has a Pozzy patch embroidered on his vest, and a Pozzy chain around his neck.

In March, he kept his promise and stopped using crystal meth.

“It was important to him that I got off that shit,” Prescott says.

FAMILY MATTERS

Brock Radford’s grandmother, Isabella Miller Haraga, was a two-time national barrel-racing champion and was inducted into the Canadian Rodeo Hall of Fame. His mom, Bobbi June, is a barrel racer, as is his older sister, Skyler. His father, Max, was a saddle-bronc rider, steer wrestler and all-around rodeo champ.

At two weeks old, Brock travelled in a trailer on the tour.

“I learned respect, and to this day try to do things the old cowboy way,” says Radford, 22 and in his fourth year as a bull rider. “I take my hat off at breakfast and hold a door open for people. There are just not enough manners these days.”

Two weeks earlier, he won his first PBR event in Swift Current, Sask. Today, he hopes to put together two eight-second rides. It doesn’t happen.

The bulls buck off 24 of 27 riders, Radford in under three seconds.

Jackson Scott smacks his head together with a bull named Marshall’s Law. Judges give Scott the option of having a second ride, but before he can take it, the medical team steps in. Brandon Thome suspects he has a concussion. Scott isn’t convinced, but retires for the rest of the night.

The 19-year-old grew up in Kelowna, B.C., and was mentored by Ty Pozzobon. He and his family visited Leanne and Luke the day after Ty killed himself.

Scott rode steers as a kid but his parents were not keen on him riding bulls. Pozzobon talked them into it.

“Every day and every bull ride I think about him,” he says.

Zane Lambert, named after the western novelist Zane Grey, wins the Wanham Extravaganza and takes home $2,957. Tanner Byrne, making a comeback after breaking his shoulder blade, collarbone and ripping muscles off his right thigh bone, finishes second and earns $2,275.

His mother was a barrel racer and his dad was a bullfighter for 25 years. His parents met on the rodeo circuit. Two of Tanner’s brothers are also bull fighters.

Like so many of them, rodeo is in the blood.

He is 25 and among the best bull riders in the world. At 6 feet 4 and 160 pounds, Byrne is also the skinniest.

“The only passion I ever had was being a bull rider and world champion,” he says. “It is a dream I had since I was 3.”

RED FLAGS

Three weeks after performing in a makeshift ring in Wanham, bull riders compete for a $100,000 prize at the most glamorous rodeo in the world. Crowds of 20,000 fill the grandstand for 10 days at the Calgary Stampede.

Byrne grew up here. He won a junior steer-riding title at the Stampede when he was 12. This year, as a tribute, he is wearing the black and white cowboy boots Pozzobon used at the Stampede in 2015.

He says he recognized changes in Ty’s demeanour the past few years.

“Looking back, there were a lot of red flags,” he says.

Byrne has a tattoo over his left rib cage, words from a speech by Theodore Roosevelt: “His place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory or defeat.”

He got the tattoo in memory of his best friend early in the year. Pozzobon had the first part of the quote tattooed on his left side in 2016: “It is not the critic who counts ... the credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena.”

After Pozzobon’s death, Radford had the words “Hippies and Cowboys” tattooed on his left arm, along with the dates of Ty’s birth and death. It is the name of a country song that was Pozzobon’s favourite. He had it tattooed on the same arm.

It is his first time to compete at the Stampede. He grew up 25 minutes from the grandstand.

“For a lot of us, winning here is more important than a Canadian championship,” Radford says.

In the dressing room before the finals, riders tape their wrists and fiddle with Flak jackets. One cowboy dozes in a chair. Another runs in place. A third does lunges down a hallway. Byrne sits in his jeans, one long leg jiggling nervously.

A few hours later, an American collects the $100,000 winner’s cheque. Byrne is bucked off, but still pleased. He won a preliminary round. Radford is bucked off as well. Afterward, he has a hoof mark on the left side of his chin and an ice bag taped to his ribs.

Thome examines him and makes an appointment for Radford the next day. He is diagnosed with a concussion, and then pulls out of three rodeos in the coming week.

“It felt like somebody hit me in the head with a baseball bat,” he says. “My vision was blurry for 90 minutes.”

He rests because of Pozzobon’s suicide.

“Before that happened, all of us bull riders were a bunch of little outlaws,” Radford says. “Now, we are really listening. You don’t know if you are one hit away from being brain dead or dying.”

The following weekend, Tim Lipsett, a 23-year-old who grew up on a ranch north of Regina, wins one round at the K-Days Rodeo, a qualifier in Edmonton for the Canadian Finals Rodeo. At the Stampede, half of the cage on his helmet was crushed by a bull.

“My jaw was sore, but that was the only problem,” Lipsett says. “I could not have been luckier.”

Lipsett’s father rode bulls. He has one brother who is a bull fighter, and another who rides bucking horses.

He rode the night before in Morris, Man., and drove 13 ½ hours to get to Edmonton. After a nap, he wins his round at the K-Days Rodeo.

“It is not just getting on the bulls that we like,” he says. “It is the miles and dedication it takes, and the pain you endure.

“I love the sport more than anything in the world. You go broke to get rich.”

LIVING IN THE MOMENT

The last stop of summer on the Canadian PBR tour is the Glen Keeley Memorial Championship in Stavely, Alta. The event is named after a local champion who died in 2000 from internal injuries suffered in a riding accident.

More than 1,500 people bring seat cushions and pack the arena in the town of 400 an hour south of Calgary.

A year ago, Ty Pozzobon competed at a rodeo in Wyoming on Saturday afternoon, and then chartered a plane so he could ride in Stavely the same night. Justin Keeley, Glen’s younger brother and a PBR judge, left a truck and keys beside an airstrip 10 kilometres away. Pozzobon hopped out of the plane, into the truck and rushed to the arena.

In the six weeks between the Stampede and here, Radford has won an unprecedented four consecutive PBR events in Canada. He receives an invitation to ride on the Built Ford Tough Series the same weekend, and turns it down. Bull riding, a weekend staple on CBS, gets higher TV ratings than NHL regular-season games in the United States. That doesn’t matter to Radford. Pozzobon rode in Stavely last year en route to winning the Canadian championship, and he hopes to do the same.

“I want to take a page out of Ty’s book,” Radford says.

Radford rides well but finishes fourth. He has a better night than Lonnie West. West bangs his head on the ground after being thrown backward off I’m a Hellion. An assessment reveals a possible concussion so he benches himself for the rest of the evening. In the dressing room, his head pounding, he decides to sit out a few weeks.

Two weeks earlier, he suffered concussions days apart. The second time, in Jasper, he was knocked out.

“When I came to, I didn’t know where I was and my left arm and left leg were tingling,” West, 21, says.

After he was thrown in Stavely, he lost consciousness as his head hit the ground.

“Everything turned white,” he says.

West grew up in Cadogan, a hamlet in southeast Alberta with 100 residents. His dad was a bull rider. So was his brother. Lonnie rode sheep as a little boy, and started to ride steers at 8. The West family had its own bucking chute, the way some families build backyard rinks.

“I love the fact that every time I nod my head, it could be the last,” West says. “In seconds, my entire life could be changed. It keeps you living for the moment.

“Anything that ain’t worth dying over isn’t worth living for.”

The Glen Keeley Memorial ends with Zane Lambert and Jared Parsonage as co-champions. Parsonage then completes a ride on a bounty bull named Johnny Ringo and earns more than $12,000 for the night.

In three years, Johnny Ringo has only been ridden successfully three times. Ty Pozzobon had one of the other two eight-second rides three months before he died.

Leanne Pozzobon says she worried less about him being injured riding bulls than she did him getting hurt while driving long distances between rodeos.

“I had to trust that he was going to be okay,” she says. “If I didn’t do that, I would have gone nuts.”

Chapter 5

An endless carpet of canola unfurls beside the dusty back roads of east central Alberta. Corn rises from the black soil. Bales of hay hopscotch around fields.

Curtis Anderson sits on the deck behind his modest home in Minburn, the hamlet his great-grandfather helped settle a century ago. There is a herd of beef cattle on Anderson’s 100 acres. His mom and dad live past the creek where he contemplates life’s incertitude and looks at the reflection of cattails shimmering off the water.

More than 15 years ago, he was knocked unconscious while riding Real Handy at one of the world’s five biggest rodeos, Alberta’s Ponoka Stampede. As the 1,500-pound animal whipped him around, they smacked heads twice. It caused a fracture at the base of Anderson’s skull, bleeding around his brain stem and intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhaging.

Within hours, Anderson underwent a craniectomy to stop the bleeding. Then he was placed in a drug-induced coma to allow swelling in his brain to recede.

He was in the back of an ambulance on the way to a rehabilitation hospital when he awoke three weeks later.

“I couldn’t walk, couldn’t talk and couldn’t move my left arm,” Anderson says. “Pretty soon, you know what you are made of.”

He wears boots, jeans and a white hat inscribed with Pozzy on one side. There is a leaflet from Ty Pozzobon’s funeral on the kitchen counter.

They became friends at Anderson’s speaking engagements on the rodeo circuit. He has spoken to 40,000 people in the past three years to raise awareness about brain injuries.

“I never saw a video of my wreck, and I don’t want to,” he says. He is 42, and drags his left leg when he walks. It took nine months before he was able to take his first steps. For months, he communicated by writing on a scribbling board.

Anderson hesitates when asked how many times he was concussed. He says two, then remembers a third. Later, he recalls two more. And then another.

Two weeks before his accident in 2002, he was knocked unconscious at another rodeo.

Anderson underwent physical therapy for 51 weeks. Fourteen years later, he still works to regain his functions. To demonstrate how far he has come, he places coins on the counter and picks up all but the smallest. He stickhandles a rubber puck around his deck. It took nine years, but he can tie his own skates, and circle a rink without faltering.

In a few days, he would speak at another rodeo. He pulls riders aside and urges them to rest when they have a head injury.

“I talk to teenagers and young bull riders,” he says. “Rather than reciting stats, I tell them my story. I am living proof of what can happen if you don’t take time to heal.”

When Anderson senses a wreck coming, he looks away.

“I can’t bear to watch,” he says.

BLEEDING FROM BOTH EARS

Saddles and a bull rope sit in the front window of Beau and Alycia McArthur’s house in Nightingale, a hamlet with 30 residents 50 kilometres east of Calgary.

As a 12-year-old in 1995, Beau McArthur rode steers at the Canadian Finals Rodeo. At 17, he won the national novice bull-riding championship. He began riding bulls professionally in 2003, and was Canada’s top rookie.

In December, he turns 35. For the past decade, he has been stricken with frontal-lobe syndrome. Nerve endings in the front of his head were severed while riding bulls. He suffers from concussion-induced depression, memory loss, anxiety and mood swings. He feels exhausted.

“I think back and wonder if I would do anything different, and the answer is probably not,” McArthur says. “I just wish I had known more about concussions back then.”

He was 5-foot-5 and 120 pounds when he rode bulls, and did not wear a helmet. He was against it as a rider, but has changed his mind since.

He is unsure how many concussions he had.

There was a bad one in 2002 at a rodeo in Taber, Alta.

He lost control as the bull spun. As he fell, he was hit in the back of the head by its horns. It hooked him three times as he lay in the dirt, and then stomped on the back of his head.

“I knew something was wrong,” McArthur says. “I was bleeding from both ears.”

Aside from the concussion, he had a skull fracture and a broken eye socket.

He was hospitalized for a week, and took a year off. Then, in 2005, he had concussions a day apart. The first was at the Ponoka Stampede. As he jumped off a bull, he struck its flank with the back of his head.

The next night, his hand got snagged on a rope as he was thrown, and he ended up beneath a bull in Williams Lake, B.C. He got kicked in the back of the head, and woke up in the hospital.

As soon as he was discharged the next morning, he and three other bull riders drove 10 hours back to Ponoka. He hoped to compete in the final round at the Stampede. The medical staff intervened.

“I put him on an exercise bike,” Dale Butterwick says. “Within minutes, he was dizzy. He was smart enough to realize he couldn’t ride.”

McArthur returned to the circuit the following year with limited success. He retired in 2007. He sought medical help, but says the general practitioners he initially conferred with lacked knowledge about head injuries.

“I wondered, ‘Why do I feel like this? Where is this coming from?’” he says. “I didn’t have emotions anymore.”

After years of brain scans, MRIs and appointments, he was diagnosed with frontal-lobe syndrome.

“It has been a struggle for us as a couple and a family,” Alycia says.

Beau and Alycia were devastated when Pozzobon took his life. They didn’t know him well, but they understood.

“For the first time, I started talking about this,” Beau says. “It opened my eyes.”

The Pozzobons want safety standards improved to protect bull riders. They want people to understand the risks associated with concussions and repeated head injuries.

“We are not trying to hurt the sport,” Luke says. “If we did that, our son would be so mad he wouldn’t talk to us.”

Chapter 6

In August of 2016, Brock Radford completed one of his two successful rides in five tries aboard Minion Stuart. After spinning clockwise 13 times in eight seconds, the massive brahma mix catapulted Radford backward over a six-foot fence.

After landing on a spectator, Radford thrust his arms in the air. Judges awarded him 88 points – half for the technical merit of his ride and half for the bull’s agility and intensity. More important, he escaped a trampling.

“It was the best-case scenario,” Radford says. “I was out of the arena, so I didn’t have to worry about his horns. When I get thrown off him, my legs are running when I am in the air.”

Named after a character in the film Despicable Me, Minion Stuart has a sweet, mottled face and horns three feet across. He weighs 1,750 pounds, and has a disagreeable disposition.

“Good bulls buck better in big places,” says Lane Skori, who owns Minion Stuart along with his dad, Ellie. “You can see their hair standing up.”

In 2015, Minion Stuart was Canada’s top bucking bull. He has appeared at the Calgary Stampede in each of the past four years, and at the PBR’s Canadian championships three times. For the past three years, he has competed at the PBR worlds in Las Vegas.

He is seven years old, and has been ridden 70 times. More often than not, he spits riders out like hay seed.

At home on the Skoris’ 10,000-acre ranch in Kinsella, Alta., Minion Stuart is suspicious of strangers. He retreats to the opposite side of his pen. He cannot be coaxed closer even with food.

Lane and his dad run Skori Bucking Bulls. They have nearly 70, a dozen of which compete at Professional Bull Riders’ events. Among them all, Minion Stuart stands out.

“He is always ready,” Lane says. “If we load the trailer with bulls and leave him at home, he hangs his head. Sometimes, he sees us getting ready and runs from two pastures over and waits beside the gate.”

The best bucking bulls in Canada can bring $100,000 on the livestock market in the United States. Breeders track bloodlines the same as they do with thoroughbred racehorses. Bucking bulls eat special food and receive better medical care than their riders. They compete at rodeos 10 to 12 times a year for eight seconds at the most, so they never get tired. They are remarkably graceful.

“To see an animal as big as they are, as athletic as they are, is phenomenal,” Tanner Byrne says. “I am a fan, but not when one is on top of me.”

Byrne has ridden Minion Stuart three times, twice successfully. The one time he was thrown off, Minion Stuart surprised him by immediately whirling to the left. It is one of only two times he has not spun to his right. Most likely, it was a calculated move.

“He thinks faster than a rider can and adjusts accordingly,” says Justin Keeley, the bull-riding judge. “If someone stays on him, he gets ornery. He knows when he wins or loses.”

When they are two years old, Ellie Skori trains bulls to buck with a dummy on their backs. At 3, they are ridden by novices in a college rodeo program.

Bulls that show no ability are sold as beef.

“It is in their best interest to buck,” Ellie says.

He rode bulls professionally, and his dad was a bull rider.

“Injuries set me back, but I would do it again,” he says. “Riders today have better protection than when I rode. The difference is that bulls are twice as good.

“When you watch them now and watch video from years ago, it is like watching the NHL Classic. Everything seems so slow.”

Minion Stuart is beloved by riders. The harder the ride, the higher they score.

“He is my favourite bull in Canada,” Tim Lipsett says. He has ridden Minion Stuart three times. He was bucked off once and got scores of 89 and 87 on the others. “He is big, scary and intimidating and bucks really hard. You know he is going to do his job. If you do yours, you are likely to win.”

In 1983, Cody Snyder earned a score of 95, the highest ever by a Canadian bull rider. Both Snyder and the bull he rode on that occasion at the Canadian Finals Rodeo, Confusion, are in the Hall of Fame.

Snyder grew up in Medicine Hat and turned pro at 16. In 1983, he became the first Canadian to win a world bull riding championship.

“Ty Pozzobon reminded me of myself,” he says. “He lived every day of his life to be a bull rider.”

At dinner in his teens, Ty would talk about it so much that his mother and sister would tease him.

“Bulls, bulls, bulls,” Amy, a barrel racer, would protest.

Ty Prescott and his father bought a half-interest in a mottled bull that Pozzobon raised. After he died, they changed its name to Live Like Ty.

Chapter 7

In May, experts in brain injuries and chronic traumatic encephalopathy gathered in Dallas. Jayd Pozzobon went, too. She stood up and talked about Ty and what had happened.

“It was emotionally draining,” she says. “I felt so much guilt over marriage issues. I was looking for answers.”

After, she was approached by some of the neurosurgeons, pathologists and scientists.

“They knew that he must have had CTE,” she says. “They said it sounded like a textbook.”

Dr. Julian Bailes, a former NFL doctor who worked with Dr. Bennet Omalu to expose the risk of brain injuries, hugged her and made a promise.

“He told me, ‘I will do everything I can to give you the answers you are looking for,’” Jayd says. “I was bawling and had full-body chills.”

The Pozzobon family donated Ty’s brain to researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

“It wasn’t a hard decision for us,” Leanne says. “We were scared. We wanted to know the scientific reason for what happened.”

Last month, at a meeting in Seattle, the results were disclosed.

An examination carried out by Dr. Dirk Keene and Dr. Christine MacDonald confirmed neuropathological changes and evidence of traumatic brain injury.

With it, Pozzobon became the first confirmed case of CTE in a professional bull rider.

“It didn’t surprise us,” Leanne says.

Dr. MacDonald says MRIs Ty had before he died helped pinpoint areas in the frontal orbital lobe of his brain where CTE was found. It is the area of the brain responsible for emotions, judgment, impulse control and memory. Tissue samples confirmed he had suffered numerous micro-hemorrhages caused by repeated trauma.

“His sample will have long-lasting impact not just for rodeo cowboys but on cases at large,” Dr. MacDonald says. “It will be used to help define the criteria of diagnosis.

“Devastations like this are awful for the family, and I applaud the Pozzobons and Jayd for wanting to understand what happened.”

The Professional Bull Riders plans to expand its medical support and protocols in Canada to include someone with authority to withhold a rider with concussive symptoms.

“We have an interest in protecting bull riders and are committed to being the group that defines safety parameters,” says Sean Gleason, the organization’s chief executive. “We are going to become much more aggressive when it comes to allowing riders to compete in any event associated with our name.”

Gleason says the PBR will control only cowboys competing at its events in Canada and the United States. He says the organization is working toward implementing more robust safety rules.

“To be effective, we have to have baseline information and be confident that the bull riders are being honest,” Gleason says. “After that, we can control the environment in which they compete. They will have to be honest and willing for it to work.”

That has already begun to happen in the aftermath of Pozzobon’s death.

Brock Radford, Jackson Scott, Lonnie West and Tanner Girletz all sat down this year at the advice of the Canadian Pro Rodeo Sport Medicine Team. Chad Besplug says the awareness created this year has possibly prevented riders from getting a hundred concussions.

“Ty’s death was the worst and best thing that ever happened to bull riding,” Justin Keeley says. Along with losing one brother to internal injuries, the PBR judge has another who sustained a traumatic brain injury. “The issue can’t be hidden in the dark anymore.”

Jayd Pozzobon shuddered at the word suicide in the months after Ty’s death.

“It still hurts, but now I realize it is real life,” she says. “It needs to be talked about more, and there needs to be more help.”

She wants to educate people through the foundation that carries her late husband’s name. She became a widow at 25. She had been married a little more than a year.

“I want the sporting world in general to be more aware of the severity of concussions and head injuries so guys like Ty don’t have to suffer,” she says. “I want to save families from what we went through.”

Tanner Byrne misses his friend. He was cremated. His ashes are with Leanne and Luke.

This week the best bull riders in the world come to Edmonton, chasing titles and a million dollars. On Nov. 9, Ty Pozzobon would have celebrated his 26th birthday. Instead he remains 25, lost on a rising star.

His Facebook page calls him a former PBR rider. Jayd Pozzobon’s Facebook status still reads Married. Luke, Leanne and Amy remain swamped by grief.

“A year ago at this time, our life was perfect,” Leanne says. “Now it has been torn apart.”

On the wall in Luke and Leanne’s home hangs a brown picture frame with two black and white photos tucked inside. On the left, young Luke Pozzobon on the back of a bucking bull, broken arm in a cast, punches the air. On the right, young Ty Pozzobon, on the back of a bucking bull, broken arm in a cast, punches the air. Below it, Ty wrote to his dad: “My father did not tell me how to live; he lived, and let me watch him do it.”

Leanne used to check to make sure Ty was safe after every ride. He told his mother she worried too much.

“I would call him and say, ‘Ty are you okay?’” she says. He would always respond the same way: “I’m okay, okay?”

After he died, she got those three words tattooed on her foot.

“He is not with us, but now I know he’s okay,” she says. “He is not in any pain anymore.”

In October 2017, Canadian bull rider Brock Radford rode Minion Stuart to victory. PBR announcer Cody Snyder takes us through what the rider – and the bull – did right.