"All adults were once children," Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote in his tongue-in-cheek dedication for The Little Prince. Now, it seems, this unassailable observation includes Neanderthals too.

In a study published Thursday in the journal Science, researchers have provided the most detailed investigation yet of Neanderthal growth and development based on the nearly complete skeleton of a young Neanderthal child recovered from a cave in northern Spain.

The results suggest that our extinct close cousins shared a growth pattern that was remarkably similar to our own – even a bit slower in some respects. If so, it means the long childhood that is associated with cognitive, social and cultural development in humans may not have been unique to our species and instead arose at an earlier time in evolutionary history, before Homo sapiens and Neanderthals branched apart.

"We were more alike than different," said Hugo Cardoso, a physical anthropologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and a member of the international team behind the study. "Neanderthals may have been just as intelligent as us with very similar social relationships."

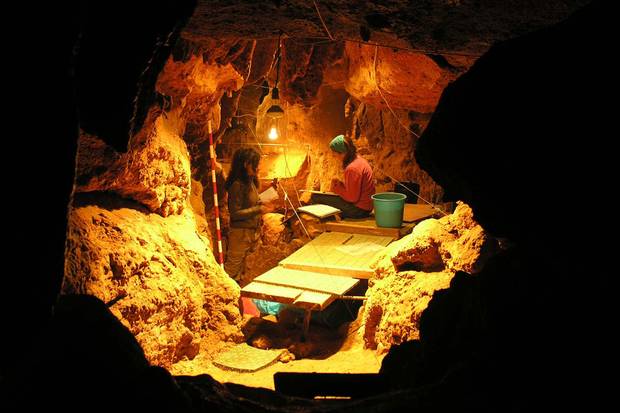

Researchers work in a cave in Spain’s El Sidron cavern system, which holds a cache of Neanderthal skeletons beleived to have belonged to a family group that lived in the area 49,000 years ago.

PALEOANTHROPOLOGY GROUP MNCN-CSIC

The finding is the latest result to come from a cache of Neanderthal remains representing 13 individuals, including adults and juveniles, that were found in the El Sidron cave system starting in 1994. The skeletons are thought to have belonged to a family group that lived in the area some 49,000 years ago, when Europe was locked in the depths of the last ice age.

Exactly what befell the group is unclear. Cut marks suggest the bones were separated after death and the flesh removed – potential signs of Neanderthal cannibalism, or of a specific burial ritual.

The focus of the new study is a juvenile skeleton known as J1, which has tentatively been identified as belonging to a young male Neanderthal. Using clues from the skeleton's teeth, the team was able to pinpoint the age at time of death at just over 7 1/2 years.

Dr. Cardoso, who specializes in growth based on bone characteristics, was then able to compare the Neanderthal's growth patterns with that of anatomically modern human children. A key part of the work involved drawing on data from a collection of unclaimed cemetery remains curated by the National Museum of Natural History in Lisbon.

Adult Neanderthals are known to have had slightly larger brains, by volume, than modern humans, a fact that some previous studies have proposed could be due to faster growth during early development.

The new finds suggest this is not the case. The young Neanderthal, J1, grew no faster than human children today and in some ways its bone development looked less mature in comparison. For example, the researchers note that some of its vertebrae had not yet fused – a detail that is more typical of human children between the age of 4 and 6.

Even that difference could be due to environmental stresses that affect growth rate rather than a true difference between species, said Erik Trinkaus, an expert in Neanderthal biology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study.

"I doubt whether there is sufficient evidence to say that Neanderthals really developed more slowly, especially in terms of brain growth," said Marcia Ponce de Leon, an anthropologist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland.

However, she also praised the study for its key finding that, apart from some obvious differences between humans and Neanderthals, the two species' growth and development patterns parallel one another closely.

"It puts the idea of human uniqueness to rest," she said.

Team members were quick to stress that a result based on the bones of one individual may ultimately prove to be an outlier, but they also noted that J1 shows no signs of abnormal development. "There is no evidence of disease in the skeleton," said Antonio Rosas, a paleoanthropologist at Spain's National Museum of Natural Sciences, who led the work.

Researchers Antonio Garca-Tabernero, Antonio Rosas and Luis Rios sit behind the Neanderthal child’s skeleton.

ANDRS DAZ-CSIC COMMUNICATION

The deeper question is what all this means for scientists trying to interpret what Neanderthals were really like, and why they ultimately lost out to our own ancestors in a Pleistocene battle for survival. The last Neanderthals are thought to have died out about 24,000 years ago. Genetic studies have demonstrated that modern Eurasians carry up to 4 per cent Neanderthal DNA in their genomes, which means there was mixing between the two species at times in the past.

If Neanderthals developed no faster than modern human, it could mean there was just as much time and possibly just as much need for a family-based community structure and for cultural exchange over a long period of maturation.

"The growth pattern of Neanderthals could accommodate the extension of those [social] processes too, as in modern humans," said Luis Rios, a co-author on the study.

Dr. Rosas added that such questions were "next steps" in the exploration of how the individuals at El Sidron lived and related to one another, and what that may reveal about human evolution.

In The Little Prince, Saint-Exupéry noted wryly that most adults fail to remember having been children. By reading the ancient bones of El Sidron, researchers may have at least saved Neanderthals from a similar fate.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL