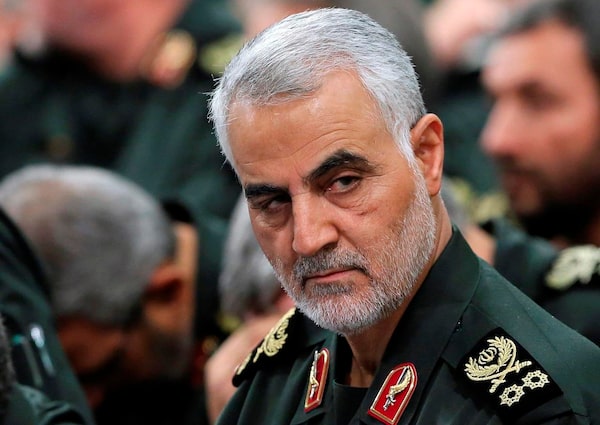

Revolutionary Guard Gen. Qassem Soleimani attends a meeting with Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Revolutionary Guard commanders in Tehran, Iran on Sept. 18, 2016.The Canadian Press

With the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani in a drone strike near Baghdad airport on Thursday, the long-running shadow war between the United States and Iran has become an open conflict.

The question of why the U.S. wanted Gen. Soleimani eliminated is easy to answer: No individual was more responsible for Iran’s spreading influence across the Middle East than Gen. Soleimani, who headed the Quds Force, the special-operations arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.

His was the hand directing everything from initial resistance to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq to more recent missile attacks on American troops still stationed in the country, as well as the targeting of oil installations in Saudi Arabia. He oversaw Iran’s military involvement in Syria as well as its influence over Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia, and was arguably the second-most-powerful person in Iran, after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Less clear is why U.S. President Donald Trump decided now was the time to assassinate a man that the U.S. military has likely had in its sights many times over the past 16 years. “General Qassem Soleimani has killed or badly wounded thousands of Americans over an extended period of time, and was plotting to kill many more … but got caught!” was the explanation Mr. Trump offered via his Twitter account on Friday. “He should have been taken out many years ago!”

There’s a reason why hashtags like #WW3 and #FranzFerdinand were trending Friday on Twitter. The leadership in Tehran clearly regard the assassination as something akin to a formal declaration of war.

While Canada, the U.S. and many other Western governments label the Quds Force a “terrorist” group, Gen. Soleimani’s death is very different from the assassinations of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden or Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the head of the Islamic State. Gen. Soleimani may have been a terrorist in the eyes of some, but he was also a key figure in a heavily militarized regime that rules a country of 82 million people, and which has powerful friends – if not allies – in Russia and China.

The killing of Gen. Soleimani was condemned by both Moscow and Beijing, and caused concern even among some traditional U.S. allies. “We have woken up to a more dangerous world,” said Amélie de Montchalin, France’s Minister for Europe. A spokeswoman for German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the world was at “a dangerous point of escalation.”

“We call on all sides to exercise restraint, and pursue de-escalation,” Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne said in a statement. “The safety and well-being of Canadians in Iraq and the region, including our troops and diplomats, is our paramount concern.”

In more violence, it was reported that another airstrike almost exactly 24 hours after the one that targeted Gen. Soleimani killed five members of an Iran-backed militia north of Baghdad, an Iraqi security official said. The Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces confirmed the strike, saying it hit one of its medical convoys near the stadium in Taji, north of Baghdad. The group said none of its top leaders were killed. A U.S. official said the attack was not an American military attack.

Gen. Soleimani was seen as a hero in Tehran and among Shiite Muslims across the Middle East, as the mastermind of a series of strategic advances that came at the expense of the U.S. and its allies over the past 16 years. But many others in the region saw him as a villain responsible for deepening the sectarian conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. The militias he directed have been blamed for tens of thousands of deaths.

Ayatollah Khamenei visited Gen. Soleimani’s family home on Friday and declared three days of public mourning. He vowed “severe revenge” for the assassination, and Iranian state television called the assassination the “biggest miscalculation” the U.S. had made since the Second World War.

Iran’s Supreme National Security Council said in a statement reported by the Associated Press on Friday that it had held a special session and made “appropriate decisions” on how to respond, though it didn’t reveal them.

In an interview with CNN, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, Majid Takht Ravanchi, said the attack on Gen. Soleimani "was an act of war on the part of the United States against the Iranian people ... The response for a military action is a military action.”

James Worrall, an associate professor of international relations and Middle East studies at the University of Leeds, said: “The assassination is probably the most significant escalation that Washington could make short of bombing Iran. Retaliation could come in pretty well any form [and] near enough anywhere.”

Tensions are high throughout the Middle East and beyond as the world waits to see where, and how hard, Iran will choose to hit back.

It’s a threat that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his team will have to quickly assess, especially with hundreds of Canadian troops deployed in Iraq at the head of a NATO mission to train Iraq’s security forces. It’s uncertain how welcome Western soldiers will be in the country after the drone strike that killed Gen. Soleimani and six others – including the head of an Iranian-backed Iraqi militia known as the Popular Mobilization Forces – near Baghdad’s civilian airport.

The most obvious target for Iranian retaliation against U.S. interests is the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow passage connecting the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman that is the transit-way for about quarter of the world’s oil supply. Iran has already shown its willingness to target oil shipping in the region; last year it was accused of attacking a series of foreign-flagged tankers in and around the Strait.

Those attacks appeared to be a response to the re-introduction of U.S. economic sanctions after Mr. Trump walked away from a deal negotiated by his predecessor, Barack Obama, that saw sanctions lifted in exchange for curbs on Iran’s nuclear program.

Oil prices jumped more than 3 per cent on Friday, passing US$68 per barrel.

American assets – including Exxon Mobil oilfields – in Iraq could also be targeted by Iranian-directed “popular anger.” The U.S. embassy in Iraq was besieged earlier this week as tensions rose after a U.S. missile strike against an Iranian-backed militia in the country, forcing the Pentagon to deploy 650 troops to protect the compound. Another 3,000 U.S. troops are on the way to Iraq in the wake of Gen. Soleimani’s killing.

Another key fault line will be Israel, which has been involved in its own shadow war with Iran for most of the past two decades. Shy of attacking the U.S. head-on, the heaviest retaliatory blow Iran could land would be to direct Hezbollah to use its arsenal of thousands of missiles to target Israeli cities, a step that would almost certainly provoke an Israeli response against Lebanon and perhaps also Syria, where Iran has been building up its military position.

If Ayatollah Khamenei and Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah decide to save that firepower for another day, Iran could still direct the Palestinian Islamic Jihad – another group that defers to Tehran – to open fire from the Gaza Strip.

Reflecting the scale of the security challenge, the U.S. urged its citizens on Friday to leave Iraq “immediately.” Security alerts were also issued for U.S. citizens in Lebanon, Bahrain, Kuwait and Nigeria.

Part of the puzzle is how Esmail Ghaani – Gen. Soleimani’s deputy, whom Ayatollah Khamenei named as the new Quds Force head on Friday – will act now that he’s the one giving the orders.

Gen. Soleimani preferred asymmetrical responses, knowing Iran could not hope to win an open conflict with the U.S. It remains to be seen whether his successor shares the same philosophy.

“Any war with Iran … will be fought throughout the region with a wide range of tools, versus a wide range of civilian, economic and military targets,” said Richard Haass, president of the New York-based Council on Foreign Relations. “The region, and possibly the world, will be the battlefield.”

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Mark MacKinnon

Mark MacKinnon