Expand your mind and build your reading list with the Books newsletter. Sign up today.

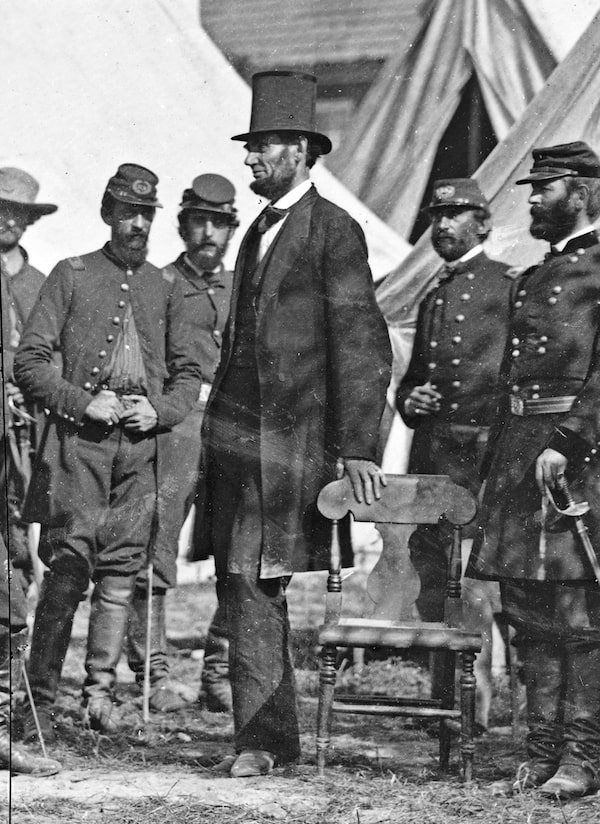

President Abraham Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers at Antietam, Oct. 3, 1862.Library of Congress

A dozen years ago this month, a great but most unusual competition in White House history came to an end. It was between George W. Bush, and Karl Rove, his long-time political advisor, to see who could read the most books each year of the presidency.

Mr. Rove won, but not decisively. And the selections Mr. Bush made were revealing. The two competitors started out with Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals, a 2005 examination of Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet that today rests on Justin Trudeau’s bookshelf as well. But then the selections diverted, with Mr. Bush’s leaning toward presidential biographies – several on Lincoln, volumes on Andrew Jackson and Ulysses S. Grant, and many others.

“We are a nation of great diversity – we have 50 different states – and our presidents are the great unifying factor,’' said Douglas Brinkley, the Rice University historian and author of biographies of Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Gerald R. Ford and Kennedy. “We live our lives through the presidents: We speak of the ‘Kennedy years,’ the ‘Johnson years,’ the ‘Trump years.’ These books show us the art of leadership.”

As an art form – one performed both by campus academics and popular historians alike – the presidential biography is remarkably resilient.

This winter alone, American publishers are bringing out three biographies of Kennedy, two of Lincoln and single volumes on Washington, Lyndon Johnson, Grant and John Quincy Adams. At the same time, biographers are working on a flood of volumes on Mr. Trump, two additional Kennedy biographies and books on James Madison, Martin Van Buren, James A. Garfield, Warren G. Harding and Lyndon B. Johnson, that are to be published later this year. And Richard Norton Smith, who has written biographies of Washington and Hoover, is at work on what is expected to be a landmark biography of Ford.

President John F. Kennedy speaks before a joint session of Congress in Washington on May 25, 1961.Anonymous/The Associated Press

“Reading presidential biographies helps presidents understand how those who came before them dealt with the challenges of the office, how they collected and absorbed information, how they considered contingencies and reacted to changing conditions or unexpected twists and turns – and how their personalities and those of other actors in the dramas of their time affected outcomes,” Mr. Rove told me recently. “It can give any president a renewed sense of humility, seeing how their predecessors dealt with terrible moments and grave decisions for which there were no easy answers.”

American presidents are major actors in history, but they are not frozen in history – and presidential biographies have historical importance. They are period pieces themselves. Whether of a contemporary president or one from the long-ago past, they are as much a reflection of the period in which they are written as they are of the period which they examine.

The presidential biography is a peculiar American genre, often heroic in nature (Abraham Lincoln and George Washington), sometimes iconoclastic (fresh views of once-derided Ulysses S. Grant), on occasion surprising (the new appreciation of Calvin Coolidge), every so often warm and forgiving (George H.W. Bush), and from time to time scathingly negative (James Buchanan and, almost certainly in the future, Donald J. Trump). In these volumes presidents have risen in esteem (John Adams, Harry Truman, even Herbert Hoover) and tumbled (Wilson and Kennedy).

Dwight Eisenhower is an intriguing example. He left office regarded as a limp loafer and golfing duffer, permitting John F. Kennedy to win the White House with a pledge to “get America moving again.” First with Fred I. Greenstein’s 1982 The Hidden Hand Presidency and then with Stephen E. Ambrose’s 1984 Eisenhower: The President and Jean Edward Smith’s 2012 Eisenhower in War and Peace, he has emerged as a mid-century presidential sage.

Eisenhower now appears as part of a vital historic tradition as well, and not only because he was the 12th general to become president. “By advocating a highway program on a gigantic scale,” Ambrose wrote, “Eisenhower was putting himself and his administration within the best and strongest tradition of 19th-century American Whigs.” That highway program looked forward as well as backward; both Mr. Trump and president-elect Joe Biden examined the Eisenhower precedent when contemplating a multi-billion dollar U.S. infrastructure offensive.

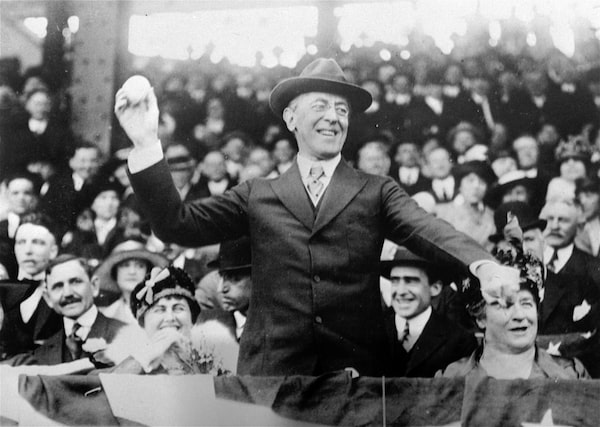

President Woodrow Wilson throws out the first ball at a baseball game in Washington in 1916.The Associated Press

Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson were both so revered by the Democratic Party that until three years ago the party’s principal state fundraising events each February and March were called Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinners. Now they are regarded as a hypocritical owner of enslaved people and a racist warrior of genocide, respectively. Then there is the curious case of Woodrow Wilson. Once considered the personification of American idealism, he now is derided as an adamantine racist and, beginning with, among other works, Thomas A. Bailey’s 1944 Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal, as a misty-eyed but mostly misled romantic in foreign policy.

Future historians, moreover, will note that Wilson so refused to engage the 1918-1919 Spanish Flu that his views on the pandemic merited not even a mention in three exceptional Wilson biographies published in the last dozen years, John Milton Cooper Jr.’s 2009 Woodrow Wilson, A. Scott Berg’s 2013 Wilson and Patricia O’Toole’s 2018 The Moralist.

The appeal of presidential biographies lies in part in the instruction that presidential lives provide for our own time.

“The presidency is about service, and when a president serves well, he teaches Americans about the uplifting value of service,” said Amity Shlaes, author of the 2013 Coolidge. “At best, a president is a moral model, showing Americans what citizens can be capable of.”

There is, moreover, implicit tension in presidential lives. Many of them – not the Roosevelts, Kennedy, the Bushes and Mr. Trump, but most of the rest – rose through personal struggle in difficult circumstances.

“I write presidential biographies because the people I have chosen to live with were leaders who brought us through times of great crises,” Ms. Goodwin, who won a Pulitzer for her 1994 No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, and who has written books about Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and Lyndon Johnson, said in an interview. “Through their lives we can see how we mustered strength through crises and we can see their triumphs and learn about their mistakes.”

Queen Elizabeth II and President Dwight Eisenhower wear affable smiles and their decorations before state dinner in the White House, on Oct. 17, 1957.AP

Sometimes presidential biographies are one-shot efforts; former Macleans editor Kenneth Whyte’s 2017 Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times is an unusual choice for a Canadian author, and as a result he offered a view of the 31st president rarely seen by Americans, by arguing, “While he clearly played important roles in the development of both the progressive and conservative traditions, neither side will embrace him for fear of contamination with the other.”

Sometimes they are multi-volume products that are the work of a lifetime; Robert A. Caro’s biography of Lyndon Johnson has run to four volumes so far, with a fifth in the works by the 85-year-old author. In his most recent (2013) LBJ volume, The Passage of Power, Mr. Caro wrote that to “watch a president, in very difficult circumstances, triumph over them” is a “means of gaining new insight into some foundational realities about the pragmatic potential in the American presidency.”

Sometimes presidential biographies are, in the characterization often applied to Mr. Trump, to be taken seriously but not literally; that’s the case with the poet Carl Sandburg’s six Lincoln volumes, published between 1926 and 1939 and for a time the most influential Lincoln biographies in print. Sometimes presidential biographies have merit for the imaginative treatment their authors provide, as York University historian James Laxer did in 2016 in Staking Claims to a Continent: John A. Macdonald, Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis, and the Making of North America.

Presidential biographies are measures of how America views itself. For decades, the model of American presidents – and thus of the American character – has been Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As a result, FDR biographies could fill the bookshelves that the Clintons – horrified at the lack of them when they entered the White House – installed in the White House.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, seated in the Yellow Room of the White House Washington, D.C. on Dec. 18, 1964, after his inauguration.The Associated Press

The classic FDR biographies are Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.’s three The Age of Roosevelt volumes (1957 through 1960) and James MacGregor Burns’s 1956 Roosevelt: The Lion and the Fox, which explains FDR through Aesop’s fable. But the more lyrical of Mr. Burns’s many FDR volumes might be the 1970 Roosevelt: The Soldier of Freedom in which he portrays the 32nd president as “a deeply divided man – divided between the man of principle of ideals, of faith, crusading for a distant vision, on the one hand; and, on the other, the man of realpolitik, of prudence, of narrow, manageable, short-run goals, intent always on protecting his power and authority in a world of shifting moods and capricious fortune.”

FDR and Lincoln often compete with Washington for the title of greatest American president, and the first chief executive has been the subject of hundreds of biographies. One recent effort of note is the 2004 His Excellency George Washington, by Joseph J. Ellis, who examines the myths (of a man who could not tell a lie) as well as “dismissive verdicts about the deadest, whitest male in American history.”

No essay on presidential biographies can omit David McCullough’s singlehanded success in rehabilitating two long-derided presidents in his 2001 John Adams and his 1992 Truman, both Pulitzer winners. Nor can it ignore Ron Chernow, whose Hamilton (though its subject never became president) inspired the Broadway hit musical. He is only the latest to celebrate the virtues of another long-underestimated chief executive in his 2017 Grant, whom he argues was instrumental not only in the Union’s victory in the Civil War but also “in realizing the wartime goals” to “gain freedom and justice for Black Americans.”

For all this, since Michael J. Birkner’s 1996 James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s, no high-profile biographer has published a biography of the president remembered mostly for supporting the notorious 1857 Supreme Court Dred Scott decision that deemed Blacks not to be American citizens, and for failing to prevent the Civil War. Often cited as America’s worst president, he does not – despite his acknowledged significance – offer the uplifting civic lessons that attract historians and biographers.

“I would not choose to write about Buchanan,’' said Doris Kearns Goodwin, “because I wouldn’t want to live with him for five years.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article included an incorrect date for publication of Ron Chernow's book Grant.