Photo illustration by The Globe and Mail

In the summer of 2003, Gerald Cotten joined a web forum that exposed him to a roiling world of shadowy digital currencies and outright financial scams. Mr. Cotten, who had just finished ninth grade at a high school in sleepy Belleville, Ont., tapped in the username “sceptre” and revealed nothing else about himself.

He soon became enthralled with the bustling site, known as TalkGold, where fly-by-night promoters and gullible investors could connect. Mr. Cotten made nearly 2,000 posts over the next decade. Hidden behind fake names and software to obscure his location, he experimented with shady ventures of his own and pushed them on the forum.

Mr. Cotten’s early online activities, which are previously unreported, proved to be an education of sorts. He apparently launched several schemes – and occasionally ran into trouble. “I sincerely ask that everyone remain calm,” reads a post from his sceptre account in 2004, when he was just 15, in what looks like a scramble to return money to at least 235 investors.

That education also gave Mr. Cotten with the wile and the nerve he needed for the business he eventually co-founded and operated as an adult: QuadrigaCX. Launched in late 2013, it became Canada’s largest cryptocurrency exchange.

Quadriga collapsed dramatically this past January, a month after Mr. Cotten died at age 30 on his honeymoon in India due to complications from Crohn’s disease.

When he died, he took his secrets with him, including how to access $214.6-million in funds belonging to roughly 76,000 users. Only he knew where the cryptocurrency – and the passwords needed to unlock it – were located. Quadriga, which he ran mostly on his own from his Halifax home, is now in bankruptcy proceedings.

In June, Ernst & Young LLP, the court-appointed trustee overseeing the proceedings, provided the first real glimpse of what Mr. Cotten was doing behind the glow of his computer screen. The young CEO transferred large volumes of customer funds into personal accounts and racked up big losses trading on other cryptocurrency exchanges.

Mr. Cotten also used money from Quadriga to fund an indulgent lifestyle, travelling the world with his wife, Jennifer Robertson, often flying on private jets. The couple acquired about $12-million in assets, including more than a dozen properties, a Cessna airplane and a yacht.

Over three years, Mr. Cotten liquidated $80-million worth of bitcoin through an offshore exchange, some of which came from Quadriga.

So far, Ernst & Young has tracked down just $33-million of the total owed to users, and the RCMP and the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation are conducting probes.

Mr. Cotten's Cessna 400 airplane, shown this past February at the Truro Flying Club in Debert, N.S., was part of the luxurious lifestyle he built with his earnings from Quadriga.Darren Calabrese/The Globe and Mail

Last month, Ms. Robertson agreed to transfer nearly all of her assets to Ernst & Young for liquidation and released a statement saying she was unaware of her husband’s “improper actions” while managing Quadriga. “I was upset and disappointed with Gerry’s activities as uncovered by the investigation when I first learned of them,” she said.

To those who knew Mr. Cotten, the news of his death and the mess he left behind was shocking. The small group of friends and family who gathered at his closed-casket funeral on a brisk day in Halifax knew him as an affable cryptocurrency obsessive with an easy smile, who was settling into a life of domesticity with his wife and their two Chihuahuas. (The dogs were at the funeral, too.) Some still find it hard to fathom that Mr. Cotten could be so reckless.

Michael Perklin, the chief information security officer at cryptocurrency exchange ShapeShift.io, occasionally had lunch with Mr. Cotten and the two played board games together. Mr. Perklin was a Quadriga customer, too, and recommended it to his father, brother and sister. All of them lost money.

“I feel cheated,” he said. “As it turns out, I befriended this criminal, this guy who ultimately stole from my family, my friends and me.”

But an online trail, pieced together over the past several months through interviews and by analyzing e-mail addresses, IP addresses, archived websites, domain registrations and correspondence, reveals a pattern of deceitful behaviour. Mr. Cotten, it appears, had experience.

Michael Perklin is an old friend of Mr. Cotten and is now chief information security officer at the cryptocurrency exchange ShapeShift.io. He says he feels Mr. Cotten cheated him and his family, who lost money on Quadriga.Ross Taylor/The Globe and Mail

Mr. Cotten's childhood home in Belleville, Ont., shown this past February. He honed his talent for building websites in high school, occasionally running into trouble for his investment schemes.Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

As a teenager in Belleville, about a two-hour drive east of Toronto, Mr. Cotten never made a secret of his interest in computers and his talent for developing websites. Sometimes, though, he seemed reticent. “As smart as he was, he was introverted,” said Kevin Song, a friend from high school. “He kept a lot of things close to his chest.”

Mr. Cotten didn’t share anything about his life as sceptre or what he was doing on TalkGold. The Globe and Mail determined the account belonged to him through an e-mail address. One of four addresses used by the account’s owner was sceptre@sceptre.me. Mr. Cotten also used that address to order services in his own name for one of his websites, according to documents reviewed by The Globe.

In January 2004, when Mr. Cotten was 15, he apparently launched a website called S&S Investments and promoted it on TalkGold. S&S was known as a high-yield investment program (HYIP), a bizarre cross between a Ponzi scheme and online gambling that littered some corners of the internet at the time.

The creator of an HYIP, almost always anonymous and unlicensed, would set up a website promoting a vague investment strategy, promise exorbitant returns, advertise in forums and through social media and accept deposits through digital currencies. That part was key. Digital currencies, even before bitcoin was launched in 2009, allowed for anonymity, so operators could hide profits outside regulated financial systems. Transactions were also irreversible, leaving no recourse for investors who wanted their money back.

The Securities and Exchange Commission in the U.S. has warned HYIPs are “often frauds," and the schemes followed a pattern. A typical HYIP paid interest for a while using funds from new investors, then vanished. According to a 2012 academic study by U.S. authors, the median lifetime of a HYIP was just 28 days, and the average investment was about US$1,000.

Some investors were genuinely duped. But others knew HYIPs were fraudulent and figured that, by getting in early and then withdrawing their money before a program collapsed, they could profit at the expense of less savvy participants.

Like many HYIPs, the website for S&S contained little information but boasted returns of up to 150 per cent. The program accepted deposits through e-gold, an early digital currency eventually shut down by U.S. authorities.

Some of the disclaimers on the site were comically amateur. “All I will say is that we will generate your return and that we are not what is called a ponzi or pyramid scheme,” one said. (The line was removed on later versions of the site.) Despite the blinding red flags, the website built up an investor base.

After a few months, S&S seemed to run short of funds to repay more than 200 investors. On TalkGold, sceptre pleaded for time. “If a threat of any kind is made...you are stating that you do not wish to receive a refund and you will not receive one,” one post said.

Some investors said they had only risked tiny amounts, but others said they put in hundreds, even thousands of dollars. One user claimed to have bet $3,000. “I knew what I was getting into, but my judgment regarding timing was extremely poor,” the user wrote on TalkGold.

While sceptre was ostensibly trying to refund investors, Mr. Cotten apparently started another HYIP called Lucky-Invest and created a new TalkGold account to promote it. But at one point, he seems to have forgotten which account he was using and answered a post directed at sceptre while signed in under his new handle.

Users immediately noticed. “I’m not trying to hide,” sceptre claimed. “My profits go to help pay refunds,” he said of the new program.

By May, 2004, the S&S website was no longer online, and soon, sceptre stopped responding to investors on TalkGold. Some posted they had received their money back, while others were frustrated by the silence. “Waiting...like a sheep waiting for his flee[c]e to grow back,” one wrote.

Still, Mr. Cotten continued to use the alias sceptre. “Nice work with S&S,” another TalkGold user wrote to him through AOL Instant Messenger in 2004, according to a chat transcript provided to The Globe.

“lol,” sceptre said, “you knew about that?”

“you make off with a lot of $$?”

“no...I was caught,” sceptre replied. “I have refunded alot. they found out my name and stuff.” He added he had no idea how his details were discovered. The other user advised him to use proxies, referring to services that deploy phony IP addresses to hide a computer’s location.

“I do now,” sceptre said. “even to talk to you lol.”

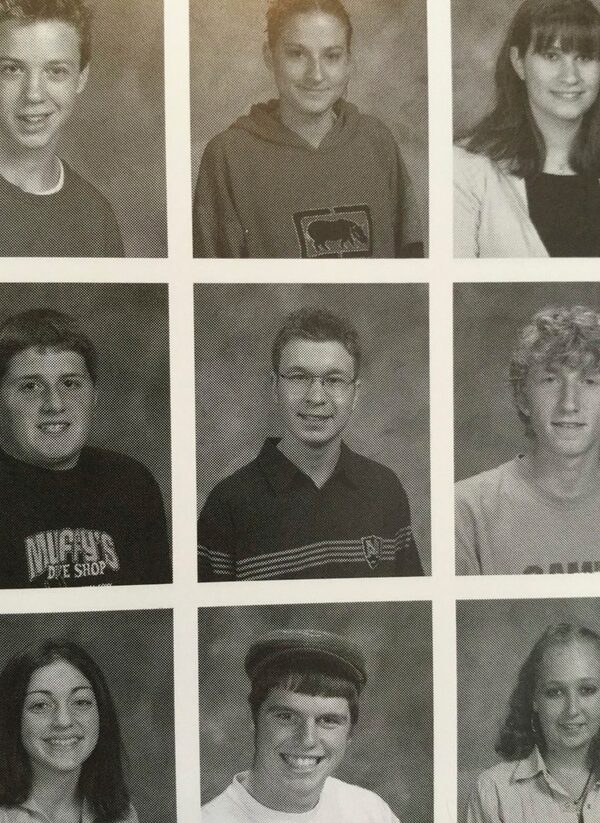

A Bayside Secondary School yearbook photo shows Mr. Cotten, middle, in Grade 11.The Globe and Mail

In August, 2006, an e-mail arrived in the inbox of an individual who ran a website that promoted HYIPs. (The Globe has granted anonymity because the source is concerned about reputational harm.)

“I am in a horrible position right now where I need to make about $5000 within a few weeks,” the e-mail began. The author ran a HYIP called United Private Investment Enterprise, or U-Pie for short, and proposed a business deal: a 25-per-cent referral commission in return for free advertising.

“You are giving away a bit of advertising in exchange for thousands and thousands of dollars down the road,” the e-mail read. “You get rich. My problems of needing $5k in a few weeks are over. Everyone is happy.” The e-mail was sent from a personal account belonging to Mr. Cotten, The Globe has found.

U-Pie, which claimed to employ three day traders to generate profit, was launched in the summer of 2006, when Mr. Cotten was preparing to attend his first year in the commerce program at York University’s Schulich School of Business in Toronto. On TalkGold, a new account under the name Voltaire popped up to promote U-Pie.

The Globe obtained a 2006 e-mail sent by Voltaire to a U-Pie investor. The IP address in the header of the e-mail indicates it was sent from a computer connected to the internet network at York, where Mr. Cotten was already living in residence.

U-Pie’s website had no detailed information about its owners or strategy. But there was a twist to the standard HYIP playbook – Voltaire offered to meet investors in person as part of a due-diligence process.

In November, 2006, a small group of U-Pie investors gathered for dinner at a vegetarian restaurant in Toronto. A well-dressed young man strolled in and introduced himself as Dan Vanaman, a 20-year-old from Florida. He was Voltaire, he said. According to one attendee, Mr. Vanaman claimed he was visiting Toronto to interview a trader for U-Pie.

When shown photographs of Mr. Cotten by a Globe reporter 13 years after the dinner, the attendee did not recognize him. The attendee could only recall that Mr. Vanaman was slim and had blonde hair, a general description matching Mr. Cotten.

By January, 2007, U-Pie claimed to have nearly $62,000 in working capital. A couple of months later, the website went offline. Users on a forum called GoldenTalk, another site for discussing HYIPs, complained about the disappearance. On TalkGold, Voltaire never logged in again.

After serving time in a U.S. prison for his role in a money-laundering scheme, Omar Dhanani, shown at left in a police photo from 2005, reinvented himself as Michael Patryn, shown at right in a YouTube interview streamed in 2015. He and Mr. Cotten founded Quadriga together.Passaic County Sheriff's Office, YouTube

Running HYIPs wasn’t necessarily easy money. Hundreds of programs all fought for the same pool of investors, and there was always the risk of getting caught. But there was also money in the underlying architecture that facilitated HYIPs: anonymous digital currencies and payment services.

Mr. Cotten turned his sights here, too, and there are indications he didn’t work alone. At some point, he met Michael Patryn. In the prebitcoin world of digital currency, Mr. Patryn was a notorious figure. On various online forums, including TalkGold, Mr. Patryn was rumoured to be hiding a criminal past and living under an assumed name.

The rumours didn’t dissuade Mr. Cotten from building a friendship with Mr. Patryn, both online and off. They got into business together, too. Eventually, the pair would found QuadrigaCX.

Mr. Patryn’s criminal past was no rumour, The Globe first reported in February. He had previously lived in California as Omar Dhanani and offered a money-laundering service through Shadowcrew.com, an online marketplace for stolen credit-card and bank-card numbers. In October, 2004, the then-20-year-old was one of nearly two dozen people arrested by the U.S. Secret Service.

In 2005, Mr. Patryn pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to transfer identification documents and was sentenced to 18 months in a federal prison. After his release in 2007, he was deported to Canada, where he lived under the names Omar Patryn and Michael Patryn. (Bloomberg has reported Mr. Patryn legally changed his name twice in British Columbia – in 2003 and 2008.)

By that time, a new digital currency called Liberty Reserve was gaining popularity. Operated by a company of the same name in Costa Rica, it had no anti-money-laundering controls and did not verify client information. Users couldn’t send money to Liberty Reserve directly, either. Instead, they wired it to third-party exchangers, which would then credit the users’ Liberty Reserve accounts with digital currency for a hefty transaction fee.

U.S. authorities were closely watching Liberty Reserve, and in 2013, the Department of Justice seized the domain name, shut down the service and indicted the founder. Authorities called the operation a “criminal business venture" that catered to users looking to launder the proceeds of HYIPs, credit-card fraud and identity theft, according to court documents. All told, the site had processed more than 78 million transactions worth a combined US$8-billion dollars. The founder was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

The department also seized more than 30 domain names registered to exchangers that worked with Liberty Reserve and took them offline, including one called Midas Gold Exchange. The Globe has previously revealed the extensive links between Mr. Patryn and Midas Gold, which launched in 2008. Investigators said the exchangers were essential for laundering money. Midas Gold had a sizable account on the Liberty Reserve platform, according to an exhibit filed with the court. More than US$5.2-million flowed through it.

That same exhibit, buried in reams of court documents, indicates that Mr. Cotten was also involved. While the name attached to the Midas Gold account on the platform is Omar Patryn, the e-mail address is listed as gerald.cotten@gmail.com, a personal account used by Mr. Cotten, the Globe has confirmed.

Mr. Patryn did not address specific questions from The Globe, but instead provided a general statement. “Gerry always referred to his prior startups as ‘small internet casinos,’” he wrote through Telegram, an encrypted-messaging app. “It wasn’t of interest to me so I didn’t really look further. They did not seem to generate much revenue.” (The improper acts at Quadriga took place after he left the company in 2016, he added.)

Mr. Cotten’s ambitions were bigger than running HYIPs and intermediaries. He also launched his own online payment service. According to a source with direct knowledge of the matter, Mr. Cotten started an entity called HD-Money in 2008.

HD-Money styled itself after Liberty Reserve and was even featured as a merchant partner on its website for a while. HD-Money promised to allow people from all over the world to transfer funds instantly for a 1-per-cent fee, according to archived versions of its website. Payments were irreversible, and “securely located outside of the reach of many governments,” the site claimed.

How much traction Mr. Cotten achieved is hard to tell, although several HYIP websites accepted payment with HD-Money. Shortly after U.S. authorities shut down Liberty Reserve, the HD-Money website was scrubbed clean, except for a disclaimer saying the service was not available in the U.S.

Paris, 2014: Mr. Cotten smiles outside the 'Bitcoin House,' a then-newly-founded cryptocurrency exchange. Mr. Cotten had founded Quadriga the previous year.Facebook

Over the years, Mr. Cotten built dozens of websites, sometimes registered in his own name. Many, such as selenagomezphoto.com or knee-pain-when-bending.com, were clearly attempts to generate ad revenue through Google searches.

There are still more sites, no longer online, that appear linked to Mr. Cotten, but where the owner was shielded behind anonymity services. The digital trails lead to many dead ends. Looking up the IP address of the server where a couple of the sites linked to Mr. Cotten were hosted, for example, reveals a constellation of long-abandoned HYIP websites.

One of those curious websites sparked to life in 2012, about a year before Mr. Cotten and Mr. Patryn launched Quadriga. It was called the Quadriga Fund and featured all the hallmarks of an HYIP: a vague investment strategy, deposits through digital currencies and unnamed operators. Quadriga Fund claimed it was managed by four investment professionals (the word “quadriga” refers to a chariot pulled by four horses), with offices in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. A Facebook page went up, too, featuring a video of a supposed long-time client.

“Over all, I couldn’t be more satisfied with the Quadriga Fund,” says the man in the video, seated in front of a computer screen. The man was actually a paid spokesperson who advertised his services on a website for freelancers, charging US$5 for a video testimonial.

Whoever created Quadriga Fund is still unknown, and it’s unclear whether the operators even raised any money for it. The site wasn’t online for long. By 2014, it was gone, and the doomed cryptocurrency exchange QuadrigaCX was open for business.

/arc-anglerfish-tgam-prod-tgam.s3.amazonaws.com/public/BK5K4HDANVFE3H2FXA4PSKXHEY.JPG) Gerald Cotten's last days

Gerald Cotten's last days

One day, he was on his honeymoon, enjoying the opulence of Jaipur. Twenty-four hours later, he was dead – taking valuable secrets and cryptocurrency passwords with him to the grave. This is what we know about how his final day unfolded.

Joe Castaldo

Joe Castaldo Alexandra Posadzki

Alexandra Posadzki