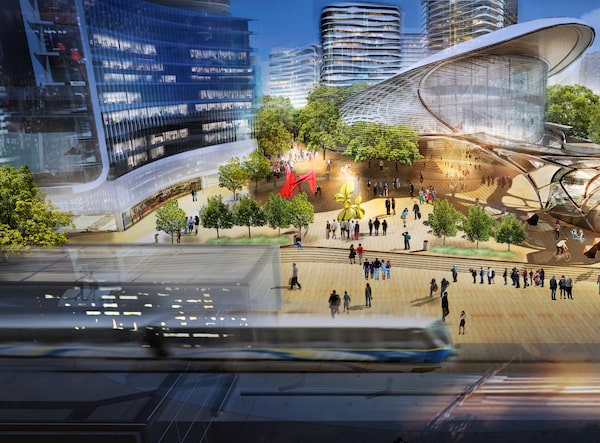

A recently approved redevelopment of the Lansdowne Centre mall will transform a huge area of Richmond, B.C.Handout

Like many suburban cities, Richmond, B.C., doesn’t have a downtown. A handful of strip malls and three vast indoor malls stretch along the main drag of this coastal city on the southern edge of Metro Vancouver. But last month, city council approved a redevelopment plan that will transform the largest, middle mall into a downtown proper for the city.

The transformation of the sprawling Lansdowne Centre mall, which covers a staggering 50 acres along No. 3 Road, is one of the largest redevelopment projects in Metro Vancouver’s history. The seven-phase plan turns the mall inside-out to create a high street brimming with local and international shops, restaurants, bars and services.

The mall’s 3,300-car parking lot – said to be the largest lot in all of Vancouver – will transform into a complete community with a potential 22 residential towers containing condos, rentals and affordable units for 10,000 residents; two office towers; a town square for events of up to 5,000 people, flanked by a community centre; a school, daycare, seniors’ home and a seven-acre park, Richmond’s new festival space.

A new network of streets will extend across the site, with a mix of vehicle roads and bike and pedestrian paths. To give some perspective of the development’s magnitude, Vancouver’s Oakridge Centre redevelopment comprises 10 towers on 28.5 acres, while the plan for Burnaby’s Metropolis at Metrotown, which will also morph into a downtown core, spreads over 44 acres.

The current parking lot at the Lansdowne Centre is said to be the largest in Vancouver.Handout

Spurred by the completion of the Canada Line rapid transit line more than a decade ago, this 4.5-million-square-foot build-out is anchored by the Lansdowne SkyTrain Station, which connects it to Metro Vancouver and the rest of Richmond. The redevelopment is part of a massive vision to transform sites at other stations along No. 3 Road into a vibrant central hub for the city of Richmond. Construction on its gateway, Lansdowne District, will begin, pending successful rezoning and presale processes, in 2023.

Lansdowne is the sole Canadian project for Vancouver-based Vanprop Investments Ltd. “We really want to create something special,” says Kim McInnes, the company’s chief executive officer. “We want to build a place that people are excited to visit and to live at, with everything in the community to have a good life.”

To complete the development, which the plan describes as “guided by principles of community and sustainability, and leveraged by unique and transformative architecture,” Mr. McInnes anticipates partnering with “Vancouver’s top-tier developers,” citing Concert Properties, Polygon, Bosa as potential builders.

The project is anchored by the Lansdowne SkyTrain Station.Handout

The project has been decades in the planning, Mr. McInnes says. The company bought Lansdowne from its founders, the Woodwards, in 1984, even then intending to carry on the retail family’s legacy by redeveloping it. At the time, the mall was considered the region’s most iconic, with both a Woodward’s department store and an Eaton’s. In the past decade, as lengthy master plan approval processes dragged on, the 1977-built centre has just managed to weather the changing nature of retail. The plan to densify and create a downtown received unprecedented public approval, Mr. McInnes says.

The developer’s crucial, early move was to retain Vancouver architecture firm Dialog (formerly Hotson Bakker Architects), whose projects include Granville Island, UniverCity, an entire village on Burnaby Mountain and, in collaboration with Bjarke Ingles Group, Vancouver House, the twisting spectacle that unfolds above a mixed-use urban village under the Granville Bridge. Dialog was also part of the team that built Richmond City Hall and the Richmond Olympic Oval, both award-winning architectural feats.

Dialog’s drawings and models for Lansdowne District establish a unique Richmond style. Green-roofed, oval-shaped mid-rise towers are laced with tree-lined streets and lushly landscaped pedestrian mews. The new retail space, which will increase from 600,000 square feet, to about 700,000 square feet, will be entirely accessed from the outdoors. “Turning the retail inside-out, from a mall to an outdoor experience, makes it more urban,” Dialog partner Joost Bakker says. “It creates a much more urban, dynamic experience.”

Tree-lined streets and pedestrian mews will run between oval-shaped mid-rise residential towers.Handout

A less visible aspect of the project that excites the lead architect is the high sustainability standard envisioned, including a sitewide, low-carbon district energy system and two mobility hubs that predict ride-hailing and bike- and car-share services dominating private automobiles. (Richmond, a low-lying floodplain, has earned the reputation as a national leader in low-carbon, sustainable urbanism, as mitigating climate change and concomitant sea-level rise is very much in its best interest.)

“Why I like working in Richmond,” Mr. Bakker says, “is that there’s a vision there. Their City Hall was ambitious. Their Richmond Oval was ambitious. This is a very ambitious project as well.”

Trinity Western University, a current Lansdowne Centre tenant, is part of the redevelopment plan. Rebecca Swaim, executive director of TWU Richmond, says the Vanprop team met with a focus group of students, prepandemic, about its future campus.

“The feedback was overwhelmingly positive,” she says. “Access to affordable housing is becoming a defining issue for university students and proximity to the SkyTrain, airport and downtown core is key for our global prospects.”

Not your parents’ mall

Vancouver leads mall redevelopments, neighbourhoods of the future

Across Canada, malls, the megafauna of the retail world, are transforming into neighbourhoods of future. The catalyst wasn’t just the demise of anchor department stores or the pandemic-accelerated rise of big box stores and online shopping. The surge in real estate prices, especially for land around mass transit hubs, has changed the metrics for valuing shopping centres. Sales per square foot have been superseded by the value of the land per square foot. This is particularly evident in land-constrained markets such as Metro Vancouver. While Mississauga’s 123-acre Square One transformation marks the largest mixed-use development in Canada’s history, Metro Vancouver is currently seeing the most mall redevelopments, with a dozen projects on the go.

In Burnaby, alone, four malls are under development, each one striving to outdazzle the other. At Metrotown, the plans include a 75-storey tower, which will make it the tallest in the province – that is, until the 81-storey, 800-foot-high pinnacle rises at the Lougheed Town Centre in a few years. Further east, in Coquitlam, the aging Coquitlam Centre is another mall turning into a downtown. Vancouver’s Oakridge Centre redevelopment, the largest in the city’s history, just received approval to build an additional 775 residential units. In Richmond, the swaths of parking lots at Richmond Centre mall are giving way to 12 new mid-rise buildings.

“The number of these types of redevelopments in a relatively small area makes Metro Vancouver unique in a global sense,” says Andrew Petrozzi, a lead researcher at Avison Young Commercial Real Estate. “Municipalities are on board to generate greater densities and that’s what makes them so attractive to developers. There’s less risk.”

Even the pandemic can’t hold back investment in B.C. shopping centres. The sale of five suburban malls in the second half of 2020 accounted for 45 per cent of the year’s total retail investment of $606-million, according to Avison Young’s B.C. Year-End Investment Review, released in March.

Despite a largely pessimistic outlook for shopping centres – Newsweek declared the indoor mall obsolete in 2008 – malls have experienced a surge in interest, with developers and city planners envisioning the mall of the future as a thriving community where people will live, work, play and eat.

As Deloitte Canada’s 2020 The Future of the Mall report suggests, “It will not be your parents’ mall – so much so that we might no longer call it a ‘mall’ anymore at all.”