Fred Lalonde is excited, though that’s not a shock—he gets excited a lot. “I want to do this,” he says, his words running into one another as if he can’t wait to get to the next sentence. “I want to do nothing but this.”

The 50-year-old entrepreneur is deep into a meeting in an industrial building in Montreal’s Rosemont neighbourhood that also houses a zinc factory and a lock museum. Hopper, the online travel company Lalonde co-founded 16 years ago, is purely virtual, so this 6,500-square-foot space is more of a clubhouse, complete with stocked kitchen, couches, conversation booths and desks for a few scattered employees.

Lalonde would normally be on Slack at home in nearby Outremont. But on this sunny Thursday in September, he’s here for a weekly catch-up with vice-president of growth Makoto Rheault-Kihara, a serious 27-year-old who looks like a first-year commerce student. The pair pore over spreadsheets as if searching a treasure map.

Most Canadian startups can only dream of their first $1 billion in revenue. Lalonde is already thinking well beyond that. With the post-COVID “revenge travel” trend still underway, Hopper is approaching the rarified 10-figure revenue mark, having surpassed US$500 million on an annualized basis this year. That’s up from US$17 million in all of 2019. He has charged Rheault-Kihara with figuring out how to crank up Hopper’s hotel booking business to US$1 billion in gross bookings, more than tripling where it is now.

Editor’s Note: For every step forward, it seems women take two back

Newcomer of the Year: How Tracy Robinson got CN Rail back on track

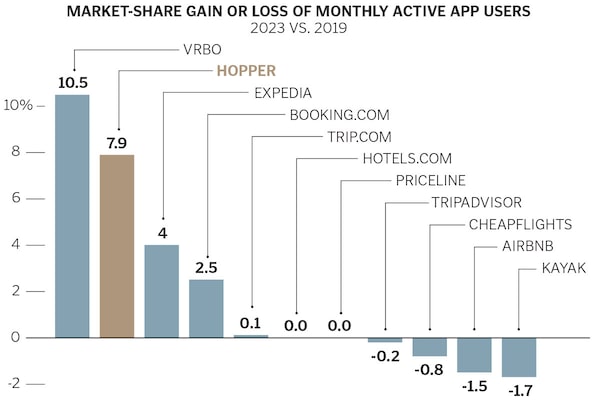

Hopper is now the third-largest online travel agency in North America, with more than 13% of the category’s share of flight bookings, a solid business in lodgings, and contracts to manage the travel businesses of Capital One Financial and other credit card issuers. It has built its business by using artificial intelligence to leverage trillions of data points, creating an app geared to Gen Z travellers. It first gained traction by advising travellers not to buy—allowing them to track prices on desired routes and sending updates until prices had fallen to optimal levels. Its app has been downloaded 100 million times.

Hopper’s data-first approach has given the company a wedge to create a much larger business—and reigning online travel kings Expedia and Booking.com have noticed. They saw their combined share of online hotel bookings drop for the first time during the COVID years, with much of that shifting to Hopper, according to Bernstein lodging analyst Richard Clarke. Both had given Hopper access to their inventory of hotel rooms, enabling Hopper to piggyback on their businesses to serve its own customers. But in July, Expedia abruptly ended its supply deal, accusing the upstart of exploiting consumer anxieties to sell them needless products. Then, on Sept. 29, Hopper ended a similar relationship with Booking.com after striking enough direct relationships with hotels to supply 65% of its room inventory and getting the rest from other lodging marketplaces.

What has the big guys so irked is Hopper’s lineup of insurance-type products, introduced in 2019, that allows customers to freeze prices, cancel or change bookings for full credit, rebook missed connections for free, or protect against disruptions. These so-called fintech offerings carry much higher margins than travel (thanks to plenty of trial and error testing by Hopper) and, if Lalonde is right, they could create new revenues for the travel industry and bring peace of mind to the frequently unpleasant experience of going places. Or, as Expedia puts it: mercilessly capitalizing on traveller angst.

For years, countless Canadian startups have pledged to become the next Shopify. Hopper has the best shot—though to be clear, it still has yet to turn a profit. (Shopify hadn’t either, when we named founder Tobias Lütke CEO of the Year in 2014.) With a valuation on paper of more than US$5 billion, Hopper is one of the most heavily financed domestic startups, with Canadian backers including OMERS Ventures, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec and Brookfield Asset Management, plus big U.S. names like Goldman Sachs, Citi and Capital One. If it can equal Shopify’s success, Lalonde will have delivered the kind of moonshot returns that have largely eluded Canadian startup investors.

What Lalonde wants, badly, is to keep growing his accommodations booking business, and fast—much faster than the company can do on its app, Hopper’s only consumer channel. Lodgings account for a considerable majority of gross travel bookings for Expedia and Booking.com but just 50% for Hopper, and the margins are much better than air. “It will take way too long in the app to reach $1 billion,” says Lalonde, sporting gelled salt-and-pepper hair, and dressed in a black knit shirt, jeans with the cuffs turned up and white sneakers. “If we wait 10 years, we’ll get there. I’m trying to do it in two.”

The problem is that 60% of all online room bookings happen through browsers. “With app-only, the math just doesn’t shake out,” Rheault-Kihara tells his boss.

The Globe and Mail

Launching an e-commerce site could deliver faster growth; it’s also a channel the giants dominate by spending heavily on Google search, while Hopper drives app traffic with ads on TikTok, Instagram and Facebook. It has looked into launching on the web twice in the past three years; both times, feedback was negative, and the efforts were shelved. Going web “could be the worst idea, because we’re giving up our best advantage” on mobile, Lalonde says. Nevertheless, the two agree to start experimenting on the web option.

That’s just one project Hopper has on the go. It’s working on more partnerships and looking to replace its loyalty program. It’s testing whether to incorporate user-created videos on its app. And it’s pushing hard to turn a profit in advance of going public, possibly by 2025, which is why, in early October, Lalonde slashed 30% of full-time staff, or 250 people, mostly in areas he says weren’t contributing financially.

Then there’s Lalonde’s side-hustle: trying to save the planet. In September 2022, he launched Deep Sky, a climate-tech startup that’s hoping to capture carbon and store it underground. Several of Hopper’s investors have also bankrolled Deep Sky, and Hopper director Damien Steel quit his post running OMERS Ventures to lead it.

If it all sounds chaotic, well, chaos is where Lalonde lives, and he’s surrounded by people who’ve strapped in for the ride. “Chaos and ambition are two sides of the same coin,” says Hopper president Dakota Smith, who’s worked with Lalonde for a decade. “If everything is under control, you’re probably not being ambitious enough.”

Hopper is what Canadian startups are supposed to be but too often aren’t: innovative, fast-moving and willing to bet on compelling signals even if it means changing everything. It’s also led by a boss who’s...a little out there. “You can say Fred is crazy-good,” says Brightspark Capital partner Sophie Forest, Hopper’s first investor. “But you can also say he’s crazy, comma, good.”

Lalonde works all the time (including at his Maine beach home, where he summers with his wife, writer Dominique Fortier, and their daughter) and says he has no friends outside of work.

He speaks in the clipped tone of someone with a perennially active mind and an accent easily mistaken for cosmopolitan American hipster (he spent part of his childhood in Ohio) even though he’s a pure laine Quebecker. During a day shadowing Lalonde, I ask if he has ADHD. “OCD,” he replies. His desk must be pristine, he says, and if he doesn’t like the font or borders on a spreadsheet, he’ll send it back till it’s perfect. He’s been known to show up late for video calls because he was fixing the creases in drapes.

After plenty of heated debate between editors and reporters from across The Globe and Mail, these are the top five executives across the Canadian business landscape that deserve to be celebrated for their outstanding achievements.

The Globe and Mail

While he runs a data company, “the big decisions, I make on instinct,” Lalonde says. Board members describe him as a candid, bold visionary. He’s a perfectionist with “an incredibly blunt way about him,” says Laurence Tosi, the former CFO of Airbnb and a Hopper investor since 2020. Forest says CEOs often try to manage their boards and only share the good news. “That’s not Fred,” she says. “There have been periods where he’d say, ‘This is not working—we might totally fail and close the company down.’”

His penchant for drama extends to his hobbies— surfing and stunt-snowboarding. His commuter vehicle of choice is an electric skateboard. “I only do things that are hard,” Lalonde says.

The same could be said for building Hopper. “I know a lot of good CEOs where the first thing they built worked well, it had product-market fit, it was the right time, and it scaled,” he says. “That was not the story of Hopper.”

Lalonde started his entrepreneurial career in his teens, selling bootlegged copies of Commodore 64 games on Quebec City’s south shore. He even hot-wired a phone booth near his home, rigging up a remote dialler to trick the phone company into letting him make free long-distance calls to download pirated game masters from California servers and transmit the data to his home. A police officer once caught him tinkering with his pirate gear; Lalonde got off with a promise that he turn his hacker’s sensibilities to non-criminal pursuits.

By the early 1990s, Lalonde was a CEGEP dropout building websites, including an ahead-of-its-time attempt to create a flight-booking service. More successful was a Montreal startup he co-founded called Newtrade. It digitally connected central reservation systems at hotel chains with individual properties to update their systems as rooms booked up, replacing faxes. Expedia bought Newtrade in 2002, and Lalonde led the Seattle-based giant’s hotels division and worked on mergers and acquisitions.

A hacker-turned tech entrepreneur, Hopper board members describe Mr. Lalonde as a candid, bold visionary.Daniel Ehrenworth/The Globe and Mail

After leaving in 2006, he decided to try building something new: a search engine for planning trips. Say you wanted a budget scuba holiday—you’d type in a few details and get back a full itinerary. To create that, Hopper would amass troves of travel-related data from the internet, harnessing the power of natural-language search to deliver optimized plans for each user. When he pitched it to Forest, she was impressed, mostly by Lalonde’s drive, quick mind and industry knowledge. Brightspark invested $500,000 in 2007 for 25% and invited him to work out of its Montreal office.

Hopper owes much of its success to the patience of Brightspark and other early investors. It was a slow build: Lalonde and co-founder Joost Ouwerkerk, an ex-Newtrader, constructed 50 computers to collect data, including the results of every online flight-price search processed through global travel-reservation systems. Hopper stored the machines in a utility room at Brightspark, and they generated enough heat to warm the whole office.

The company relocated to Rosemont and expanded to Boston in 2011 because that’s where the data-science talent was. But Hopper got an unflattering reputation. A Boston Globe correspondent in 2013 sniffed in a blog, “Hopper seems to be stuck in an endless loop of data collection, design and software development.”

Hopper finally launched its website in January 2014 and generated little interest. But a tool hidden on an inside page changed its destiny. Using all that fare-quote information, a Hopper data scientist had built a search engine that could predict the best time to book flights. A New York Times travel writer tried it out and discovered it was cheaper to book on Thursdays than on weekends, and to fly out on Wednesdays instead of Sundays. His April 2014 article brought a flood of traffic to Hopper’s website.

Lalonde immediately wanted to pivot purely to predicting airfares—and do it all through a smartphone app, despite having no staff with mobile development experience. The board was split; Lalonde said he’d do it anyway. “We have product-market fit. Nothing else matters,” he told directors. Several product managers and engineers quit.

After spending six years and $10 million, “it was just a shock, because so much energy had been spent on the previous version of Hopper,” says Forest, though she adds it was the right decision.

Hopper launched the app in early 2015, telling users what they should expect to pay for specific flights and whether they should wait for prices to drop, sending updates to keep them engaged. Apple named Hopper one of the year’s best apps, and by late 2016 it had been downloaded 10 million times. Airbnb user polls revealed a high number of its customers used Hopper to scope out flights, prompting the room-sharing giant to try to buy Hopper. But Tosi, who was with Airbnb at the time, says, “Fred gave us a number that was so off-the-charts, it was clear he didn’t want to sell.”

Lalonde realized Hopper had to do more than make recommendations; it needed to sell tickets to ensure consumers locked in those predicted airfares. Hopper began selling flights within a few months, and quickly expanded to hotels and, later, car rentals and short-term home rentals.

But Lalonde grew frustrated as Hopper missed product deadlines. He decided to split the company into small units, each one a mini-company responsible for most business functions, including product, sales and HR. Lalonde knew he’d “break things,” but he felt it would reaccelerate the organization. During a flight from Boston to Montreal just before the pandemic, he told Forest he’d even disband the engineering department, downshifting employees to the individual units.

“Fred. Please, don’t,” she told him. The company had just promoted its VP of engineering to chief technology officer, and Forest was afraid he’d leave—which he soon did. “I was scared,” she recalls. Sure enough, the initial failure rate among leaders in their small-unit roles was “horrific—like 50% churn” says Lalonde. “It looked like I destroyed my company.”

Meanwhile, Hopper was trying to improve revenues tied to air bookings, which carry slim fees—up to 2% of fares. Lalonde and Smith realized many air-only online agencies made money charging punitive fees. The pair wondered what ancillary services (later called fintech) they could sell that flyers would willingly pay for.

Each offering took a while to get right—particularly charging customers to freeze prices, because Hopper didn’t control seat inventory. Plus, the company took on the risk of funding payouts; if it got the math wrong, it could lose a lot (and did on some products early on). Because there were so many variables, Hopper would dynamically price each offering, meaning each traveller paid a different amount, starting under $10 and now averaging $40. “It took a lot of experimentation and customer feedback and pricing analysis to get it right,” says Ella Alkalay Schreiber, general manager of Hopper’s fintech division.

Some products were easier, like disruption protection: Hopper would automatically rebook a customer on a different airline or pay a refund if their flight was late for a connection. Another hit: “leave for any reason.” Customer surveys revealed many users feared their partners would hate the hotels they booked, so Hopper offered, for a fee, to rebook them at another hotel, no questions asked.

By February 2020, the company had spent nearly US$200 million of venture capital, but everything was clicking. That month, it had 5.3 million monthly active users and US$80 million in gross bookings. Revenue was US$4.6 million, up 452% from the previous February. As he made the rounds for a planned financing of hundreds of millions of dollars, Lalonde told prospective investors Hopper would hit US$99 million in revenue that year and surpass US$370 million in 2021. Fintech was working: Gross revenue per price-freeze customer was US$34.56 in January 2020, five times higher than the previous quarter. Gross margins for those products were nearly five times higher than the 11.7% for travel. The single-threaded structure was gelling.

Then COVID-19 hit.

In addition to Hopper, Mr. Lalonde founded climate-tech startup Deep Sky. Its aim is to build vast carbon-removal and sequestration operations across Canada, then to store that carbon underground.Daniel Ehrenworth/The Globe and Mail

The pandemic was a near-death experience for Hopper. Until governments agreed to help refund airfares, it looked like widespread shutdowns would vaporize its resources. It took Hopper months to process hundreds of thousands of refunds, and many customers lashed out on social media and to consumer agencies. Lalonde’s phone number was leaked online, and he was flooded with complaints. “You had people saying, ‘I got fired—if I don’t have this $1,000 back, I can’t feed my kids,’” he says.

Though he believed the industry would suffer for years, Lalonde was determined to close a financing—at a higher valuation than his last fundraise in late 2018, but less than originally anticipated. As negotiations dragged on, Lalonde grew impatient. Hopper was losing $1 million a week. If he couldn’t close the deal soon, he warned investors he’d have to fire 95% of his employees.

Tosi, whose private firm, WestCap, had signed on to invest, says despite the turmoil, he admired Lalonde’s tenacity and trusted the company would prevail. WestCap and Montreal’s Inovia Capital signed on to lead a US$70-million funding in April 2020. Once the terms were set, Hopper cut close to half its 340 employees.

Then something surprising happened. While business travel shut down, Gen Zers kept flying to domestic destinations. Because flight prices collapsed, Hopper’s app kept signalling that now was the time to buy. And Hopper’s young customers loaded up on its fintech products to backstop their uncertain travel expenditures. Hopper’s revenues doubled in 2020, then increased by 300% in 2021 as Hopper became the most downloaded travel app in the U.S.

After turning down a couple of partnership entreaties from U.S. credit card giant Capital One, Hopper reconsidered. Capital One signed on Hopper in 2021 to help run its travel-booking and loyalty rewards service for tens of millions of cardholders, including offering the price-freeze and cancel-for-any-reason products. The financial services giant also invested in the Montreal company, starting with a US$170-million funding round it led that year.

Since then, Hopper has teamed up with Commonwealth Bank of Australia and Brazil’s Nubank for similar deals. Air Canada added Hopper’s cancel-for-any-reason protection in a revenue-share deal this year, and Uber is testing travel sales in the U.K. through Hopper. Those deals account for most of Hopper’s revenue.

Despite its success, Lalonde’s rating on employer-grading website Glassdoor stood at 57% before this year’s layoffs. “I’m actually shocked it’s that high,” Lalonde says when I ask him about the rating. “I would have given you 40.”

Lalonde isn’t big on employee engagement. Hopper’s priorities are customers, speed and revenue. “We tell our employees, ‘I don’t matter. You don’t matter. The customer matters,’” he says. “Employee happiness is not a goal. It’s not valued by investors, and our customers don’t care if you’re happy.”

That said, Lalonde has a core group of executives, mostly in their 20s and 30s, who’ve not only earned his trust but are free to challenge the boss. Those who thrive at Hopper, says Schreiber, “love nailing hard problems, thinking critically about them and aiming for the big bets.”

As Hopper started to take off in the late 2010s, Lalonde thought he’d do right by the planet and sponsor a reforestation program to offset the carbon his industry produces. But the more he read about climate change, the more he worried.

Lalonde now talks in stark terms about looming catastrophes wrought by rising temperatures and sustained droughts. To fix the problem, he believes we must remove all the carbon we’ve pumped into the environment since the Industrial Revolution. The cost will be inconceivably high—but in Lalonde’s mind, we can’t afford not to. “We are going to have to build, over the next two to three decades, an industry that is larger than oil and gas, just for the removal,” he told The Globe and Mail’s Road to Net Zero summit in June. (Lalonde still drives an Audi gas-powered car, which he admits “is one of my moral dilemmas.”)

Even by Lalonde’s standards, Deep Sky is a big bet. The climate-tech startup’s aim is to build vast carbon-removal and sequestration operations across Canada, then to store that carbon underground. Revenue will come from selling carbon credits. Tosi and Ouwerkerk are co-founders (the latter, who left Hopper last year, is CTO), and Smith and Forest sit on the board.

Carbon capture and storage is a bit of a holy grail, particularly in the oil industry, which is desperately seeking a net-zero emissions solution that will allow producers to continue pulling fossil fuels out of the ground. But success remains largely hypothetical, save for some small-scale installations. Lalonde, typically, has something far larger in mind, though he admits there are plenty of unknowns, including the market for carbon credits, whether the tech will work at scale and legislative issues.

This year, Deep Sky has quickly raised more than $75 million in capital from Brightspark, White Cap Venture Partners, the Quebec government’s investing arm, OMERS Ventures and BDC. It has recruited staff, struck partnerships and worked to secure locations for pilot facilities. Lalonde also convinced Steel to leave OMERS to lead Deep Sky, even though he has no climate-tech qualifications. And he’s brought on McKinsey sustainability expert Phil De Luna as chief carbon scientist; Gregory Maidment, who oversaw one of Canada’s three underground carbon storage facilities, is director of subsurface.

“Honestly, I would have died, another six months” of juggling both companies, Lalonde admits during a meeting with a BMO banker. “There have been times where I couldn’t give the right attention to the right thing, and I feel guilty, where teams are working and you get pulled off on the other side.” With Steel on board, “I feel like we have restored some cosmic balance,” he says.

Lalonde’s divided attention is bound to raise questions as Hopper prepares to go public, as will Deep Sky’s premise. Climate policy expert Bruce Lourie, president of Toronto think tank Ivey Foundation, puts direct carbon capture from the air (DAC) well down the list of climate priorities, behind things like curbing methane emissions, transitioning off fossil fuels and capturing carbon at source. He thinks DAC won’t reach its potential for decades, will be “extremely expensive” to build and require huge amounts of energy. “It’s essentially like an insurance technology if we fail to do all the rest,” he says. Lourie estimates Lalonde would have to build hundreds of facilities to extract the carbon equivalent of Canadian methane emissions alone—and “that’s one little part of overall emissions.” Lots of tech entrepreneurs “have created apps and made a lot of money, and now they’re going to solve climate change? There are no apps for climate change.”

That isn’t stopping Lalonde. He knows he has the attention of bankers eager to take Hopper public, and he’s using that leverage to get them in on his climate play, too. “They realize Deep Sky will be an enormous company that will go public, so they actually want that relationship,” he says.

If building an online travel contender wasn’t challenging enough, getting everything to go Deep Sky’s way sounds much tougher. But Lalonde likes hard things—and the harder he tries, the more people he seems to attract. “There will be a whole bunch of challenges that even Fred doesn’t fully understand yet,” says Ouwerkerk. But when Lalonde invited him a year ago to join Deep Sky, “I didn’t even have to think twice. I was like, ‘Yes please.’”

So let’s check that itinerary again: Make Hopper profitable, build a long-odds climate startup, potentially take two companies public—and just wait till you hear what other startup ideas Lalonde has up his sleeve. For his next venture, he’d love to build small nuclear reactors or electrify the roads to power battery-powered cars. That is one busy bunny.

Your time is valuable. Have the Top Business Headlines newsletter conveniently delivered to your inbox in the morning or evening. Sign up today.

Sean Silcoff

Sean Silcoff