Saulnierville, N.S., 2020: Members of the Sipekne'katik First Nation load lobster traps onto the wharf on Sept. 17 after launching their own self-regulated fishery.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

Twenty years before a wharf in Saulnierville, N.S., became a flashpoint in the fight over Indigenous fishing rights in Atlantic Canada, a similar scene played out in New Brunswick on the water outside Miramichi.

Angry that Mi’kmaq fishers were harvesting lobsters outside the federally-approved season, a flotilla of more than a hundred fishing vessels chased Indigenous boats, pulled their traps from the water and sparked a wave of vigilantism, arson and brawls in what became known as the Burnt Church crisis.

“Everyone was concerned that people were going to die,” said Herb Dhaliwal, the former federal fisheries minister who was in charge at the time. “I had commercial fishermen saying ‘we’re going to bring our guns and we’re going to shoot anyone fishing our lobster.'”

It was a violent, emotional battle over the Mi’kmaq people’s right to set their own rules for a commercial fishery. Two decades later, that tension remains – this time, causing strife in Canada’s most lucrative lobster fishing zone in southwestern Nova Scotia.

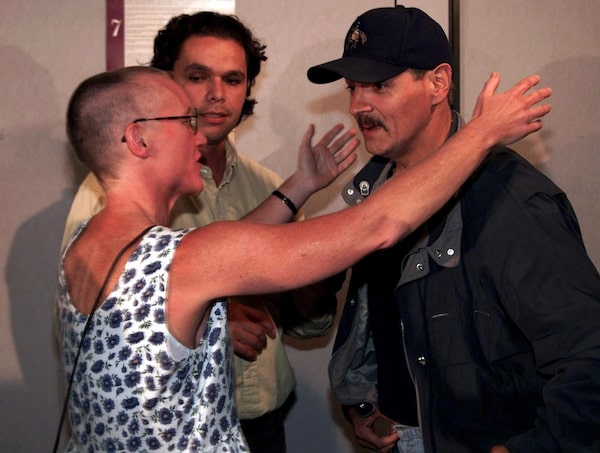

Like Burnt Church, this latest lobster dispute can be linked back to 1999′s Marshal Decision, when the Supreme Court of Canada sided with Donald Marshall Jr., a Mi’kmaq man charged with fishing and selling eels without a licence. That landmark decision affirmed Indigenous people’s right to earn a “moderate livelihood” from fishing. But the ruling also left a lot of room for interpretation – including defining what a moderate livelihood actually looks like, and how that fishery should be regulated.

Halifax, 1999: Donald Marshall Jr., right, is greeted by lawyer Anne Derrick, left, as Mi'kmaq lawyer Bernd Christmas looks on. His case would play a pivotal role in the Burnt Church dispute a year later.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/CP

The federal government negotiates fishing agreements band by band, but some, such as the Sipekne’katik First Nation, have not wanted to make the concessions over control demanded in those deals. Earlier this month, on the anniversary of the Marshall Decision, Sipekne’katik decided to assert their treaty rights, issuing their own commercial fishing licences and announcing they would determine for themselves what a moderate livelihood means. They awarded their first fishing licence to Randy Sack, the son of Mr. Marshall.

It’s believed to be the first Mi’kmaq-managed commercial fishery in the province. But it’s also prompted demonstrations and angry clashes in Saulnierville with large crowds of non-Indigenous fishers, angry that a lobster harvest was taking place after the local season had closed. Sipekne’katik fishers say their boats were blocked by more than a hundred vessels when they tried to leave the harbour, chased on the water and shot at with flare guns. Police made several arrests after supporters for both sides got physical, and are investigating complaints of sabotage against Sipekne’katik equipment.

“I don’t think we should be surprised at all that there’s a high degree of frustration among many of the First Nations. There’s been a void on the part of the federal government,” said Wayne MacKay, a law professor at Dalhousie University. “The Department of Fisheries has not done enough to respond pre-emptively to what everyone should have known would be this kind of tension and unrest."

After days of confronting the Mi’kmaq fishers and their supporters on the wharf and water, the fishers changed tactics and began targeting people who buy Indigenous-harvested lobster. They surrounded the house of one alleged buyer, claiming Indigenous-caught lobster are fuelling a black market in the province.

Jenica Atwin, a Fredericton MP and the Green Party’s fisheries critic for Atlantic Canada, argues disputes like this one will keep happening until Fisheries and Oceans Canada clarifies how Indigenous commercial fisheries everywhere can operate. “Without that clarity, and that leadership from the federal government, it’s just going to continue. This is just going to keep happening again and again,” Ms. Atwin said. “The history is there, the ruling is there and it’s laid out very plainly for anyone who’s willing to take the time to learn about it."

Meteghan, N.S., 2020: Lobster traps belonging to Sipekne’katik fishermen lie dumped outside the Department of Fisheries and Oceans office, a protest by non-Indigenous fishermen who denounced the First Nation's actions.Ted Pritchard/Reuters/Reuters

Many other First Nations are watching the Sipekne’katik talks closely. In Cape Breton, the Potlotek First Nation has already announced plans to launch their own self-managed commercial fishery in October – and sell their catch, something that’s not permitted under communal food fishery licences that the allow Mi’kmaq to fish out of season for personal or ceremonial use.

The federal government insists it must manage all commercial fisheries in Canada, while many First Nations argue they have the right to regulate their fishing as an extension of self-governance.

Federal Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan – who initially said anyone fishing commercially without a licence may be subject to enforcement action – is now in negotiations with the Sipekne’katik First Nations on establishing a moderate livelihood fishery, according to the band. She declined an interview request for this story, but her office said she’s trying to resolve the dispute.

Unlike Burnt Church, where fisheries officers rammed Mi’kmaq boats and engaged in violent arrests on wharfs and at sea, her officials have stood on the sidelines in Saulnierville, a rural Acadian village about 50 kilometres north of Yarmouth.

Ms. Atwin says the dispute is really about race. She’s troubled by reports that Indigenous people have been refused hotels, gas, and even food from local businesses around Saulnierville. When Clearwater, a Canadian seafood giant, was found guilty in 2018 of endangering lobster stocks by repeatedly ignoring federal warnings over the illegal storage of lobster traps on the ocean bottom, there wasn’t a fraction of this anger, she said.

“When Clearwater Seafoods pled guilty to a gross violation of regulations governing its traps two years ago, we didn’t see this level of public outcry. What is happening in St. Mary’s Bay is about racism,” Ms. Atwin said.

Neguac, N.B., 2000: Federal fisheries officers load lobster traps on the wharf during the Burnt Church dispute.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/CP

Sydney, N.S., 2000: Donald Marshall Jr., middle in grey shirt, walks in a peaceful protests for Indigenous treaty rights.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/CP

In Burnt Church, non-Indigenous fishers argued their main concern was conservation, worried that a Mi’kmaq fishery operating outside federal regulation would hurt lobster stocks. The same argument is being made now. “It is not appropriate for anyone to fish in a lobster breeding ground during the moulting season and destroy the resource for all the generations coming in the future,” said Colin Sproul, president of the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fishermen’s Association.

Commercial fishers say the off season, running from late May until late November, is a critical time for the crustaceans time to moult and reproduce. They’re angry Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) hasn’t acted to stop the Sipekne’katik fishers, and dumped hundreds of their traps in front of a local fisheries office in protest.

The resource, however, does not appear to be at risk. The amount of lobster caught each year has grown steadily for decades – reaching historic levels in recent years. It’s now a $1-billion industry in Nova Scotia alone.

The worst offenders when it comes to conservation are not Indigenous fishers, according to enforcement statistics. Of the 2,252 charges laid by DFO between 2015 and 2019 for violations, including fishing out of season, all but a “small fraction” were connected to non-Indigenous fishing crews, according to the federal department.

The fishing zone that governs the waters of southwestern Nova Scotia is the most lucrative lobster ground in Canada, with more than 1,660 lobster licences supplying a local sector that employs around 5,000 people. Each licence can use up to 375 traps. Lobster catches here were worth more than $498-million last season. The Sipekne’katik First Nation’s entry into this fishing zone represents a tiny portion of the larger commercial fleet – just seven lobster licences, with a total of 350 traps. There are about 10,000 licensed lobster harvesters in the Atlantic region, divided among 45 fishing zones each with their own season, designed to control conservation and ensure a steady market supply of the crustaceans.

“The amount of fishing done by all Aboriginals is insignificant compared to the non-Aboriginal fishery, especially on the south shore of Nova Scotia,” said Dr. MacKay, the Dalhousie law prof. “I don’t buy the conservation argument. What this is really about, I think, is strictly about protecting economic interests."

Saulnierville, 2020: Sipekne'katik fishermen load traps. The Sipekne'katik have only seven lobster licenses in southwestern Nova Scotia's fishing zone.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

The lobster fishery may be lucrative, with jobs where you can earn more than $100,000 in a just few months work, but it’s also expensive and difficult to break into. Many fishers are carrying staggering amounts of debt to pay for a lobster licence that can cost approximately $800,000, plus hundreds of thousands more to purchase a lobster boat.

Some of them resent Indigenous fishers who have received federal aid. Ottawa spent $354-million between 2000 and 2007 on commercial fishing licences, fishing vessels, gear and training for 32 First Nations in Atlantic Canada through negotiated agreements. The Sipekne’katik band was among the communities that received funding.

Those agreements were an acknowledgment that prior to the Marshall decision, Atlantic Canada’s Indigenous people were largely excluded from the commercial fisheries, Mr. Dhaliwal said.

He argues programs like those have benefited Indigenous communities immensely, creating valuable fishery jobs and lifting many families out of poverty. But the trade-off is they have to agree to federal regulation, he said.

“They can’t just be fishing however and whenever they want,” he said. “They have a right to a commercial fishery, but it has to be done in an orderly, regulated way.”

At the time of the Marshall decision, the value of the commercial fishery from Mi’kmaq and Maliseet First Nations in the Maritimes and Gaspé region was estimated at $3-million. By 2015, those same communities harvested $145-million worth of seafood, according to the DFO. That’s proof, Mr. Dhaliwal says, that these agreements are working.

In the past year, the Trudeau government has also reached “moderate livelihood” agreements with three bands, one in Quebec and two in New Brunswick, with deals promising a “collaborative” approach to regulation and conservation.

Members of the Sipekne’katik First Nation say they also want to manage their own fishery, arguing access to fishing is a birthright and they should be allowed to regulate their own fleet without any federal interference.

“We don’t need governance from the Canadian government. We govern ourselves,” said Robert Sillyboy, one of the Sipekne’katik fishers.

Saulnierville, 2020: A woman wears a face mask honouring the Treaty of 1752 at a ceremony for the Sipekne'katik fishery.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press/The Canadian Press

Unlike Burnt Church, this time around the Mi’kmaq fishers seem to have more public support, or at least a broader understanding of treaty rights, on their side. In response to the events at Saulnierville, some restaurants in Halifax made a small, but symbolic gesture against the larger commercial fishery – pulling lobster, that iconic east coast seafood, off the menu.

The Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs, meanwhile, say they’ve been trying to negotiate a deal for a moderate livelihood fishery with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans for many years. But the options presented by federal government infringe too much on their treaty rights, the group says.

The Mi’kmaq people will continue to fish as they always have, according to the assembly. The chief says what needs to change is how Canadians respond to it.

“Despite our rights being affirmed by the highest courts in the country, exercising these rights continues to bring frustrations, conflict and hardships to our people,” said Chief Terrence Paul, fisheries lead for the assembly.

"Our communities are going fishing and we want to ensure that they don’t have to be fearful of being harassed or charged.”

Saulnierville, 2020: A Sipekne'katik fishing boat heads back to port.Ted Pritchard/Reuters/Reuters

Editor’s note: An earlier photo caption included an incorrect description of a flag.

Our Morning Update and Evening Update newsletters are written by Globe editors, giving you a concise summary of the day’s most important headlines. Sign up today.

Greg Mercer

Greg Mercer