PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: THE GLOBE AND MAIL

On the morning of Dec. 31, as word of a troubling new outbreak in China began to reverberate around the world, in news reports and on social media, a group of analysts inside the federal government and their bosses were caught completely off guard.

The virus had been festering in China for weeks, possibly months, but the Public Health Agency of Canada appeared to know nothing about it – which was unusual because the government had a team of highly specialized doctors and epidemiologists whose job was to scour the world for advance warning of major health threats. And their track record was impressive.

Some of the earliest signs of past international outbreaks, including H1N1, MERS and Ebola, were detected by this Canadian early warning system, which helped countries around the world prepare.

Known as the Global Public Health Intelligence Network, or GPHIN, the unit was among Canada’s contributions to the World Health Organization, and it operated as a kind of medical Amber Alert system. Its job was to gather intelligence and spot pandemics early, before they began, giving the government and other countries a head start to respond and – hopefully – prevent a catastrophe. And the results often spoke for themselves.

The Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), part of the Canadian government, was instrumental in detecting potential threats including an Ebola outbreak.AurÈlie Marrier d'Unienville/The Associated Press

Russia once accused Canada of spying, after GPHIN analysts determined that a rash of strange illnesses in Chechnya were the result of a chemical release the Kremlin tried to keep quiet. Impressed by GPHIN’s data-mining capabilities, Google offered to buy it from the federal government in 2008. And two years ago, the WHO praised the operation as “the foundation” of a global pandemic early warning system.

So, when it came to the outbreak in Wuhan, the Canadian government had a team of experts capable of spotting the hidden signs of a problem, even at its most nascent stages.

But last year, a key part of that function was effectively switched off.

In May, 2019, less than seven months before COVID-19 would begin wreaking havoc on the world, Canada’s pandemic alert system effectively went dark.

Amid shifting priorities inside Public Health, GPHIN’s analysts were assigned other tasks within the department, which pulled them away from their international surveillance duties.

With no pandemic scares in recent memory, the government felt GPHIN was too internationally focused, and therefore not a good use of funding. The doctors and epidemiologists were told to focus on domestic matters that were deemed a higher priority.

The analysts’ capacity to issue alerts about international health threats was halted. All such warnings now required approval from senior government officials. Soon, with no green light to sound an alarm, those alerts stopped altogether.

So, on May 24 last year, after issuing an international warning of an unexplained outbreak in Uganda that left two people dead, the system went silent.

And in the months leading up to the emergence of COVID-19, as one of the biggest pandemics in a century lurked, Canada’s early warning system was no longer watching closely.

When the novel coronavirus finally emerged on the international radar, amid evidence the Chinese government had been withholding information about the severity of the outbreak, Canada was conspicuously unaware and ultimately ill-prepared.

But according to current and former staff, it was just one of several problems brewing inside Public Health when the virus struck. Experienced scientists say their voices were no longer being heard within the bureaucracy as department priorities changed, while critical information gathered in the first few weeks of the outbreak never made it up the chain of command in Ottawa.

Mortuary workers at a hospital morgue in eastern France in April. Early detection of the COVID-19 threat could have helped countries prepare for the arrival of the virus in advance.SEBASTIEN BOZON/AFP/Getty Images

‘We need early detection’

The Globe and Mail obtained 10 years of internal GPHIN records showing how abruptly Canada’s pandemic alert system went silent last spring.

Between 2009 and 2019, the team of roughly 12 doctors and epidemiologists, fluent in multiple languages, were a prolific operation. During that span, GPHIN issued 1,587 international alerts about potential outbreak threats around the world, from South America to Siberia.

Those alerts were sent to top officials in the Canadian government and throughout the international medical community, including the WHO. Countries across Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa also relied on the system.

On average, GPHIN issued more than a dozen international alerts a month, according to the records. But its purpose wasn’t to cry wolf. Only special situations that required monitoring, closer inspection or frank discussions with a foreign government were flagged.

GPHIN’s role was reconnaissance – detect an outbreak early so that the government could prepare. Could the virus be contained before it got to Canada? Should hospitals brace for a crisis? Was there enough personal protective equipment on hand? Should surveillance at airports be increased, flights stopped, or borders closed?

This need for early detection sprang from a climate of distrust in the 1990s, when it was believed some countries were increasingly reluctant to disclose major health problems, fearing economic or reputational damage. This left everyone at a disadvantage.

For Canada, the wake-up call came in 1994 when a sudden outbreak of pneumonic plague in Surat, India, sparked panic. Official information was sparse, but rumours promulgated faster. As citizens fled the city of millions, many on foot, others boarded planes.

Public Health officials in Ottawa were soon alerted to an urgent problem: Staff at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport, fearing exposure to the plague, threatened to walk off the job if a plane arriving from India was allowed to land. The government scrambled to put quarantine measures in place.

“We were caught flat-footed,” said Ronald St. John, who headed up the federal Centre for Emergency Preparedness at the time. The panic demonstrated the need for advance warning and better planning.

“We said, we’ve got to have early alerts. So how do we get early alerts?”

Waiting for official word from governments was often slow – and unreliable. Dr. St. John and his team of epidemiologists didn’t want to wait. They began building computer systems that could scan the internet – still in its infancy back then – at lightning speed, aggregating local news, health data, discussion boards, independent blogs and whatever else they could find. They looked for anything unusual, which would then be investigated by trained doctors who were experts in spotting diseases.

It was a mix of science and detective work. A report of dead birds in one country, or a sudden outbreak of flu symptoms at the wrong time of year in another, could be clues to something worse – what the analysts call indirect signals.

Find those signals early enough, and you can contain the outbreak before it becomes a global pandemic.

“We wanted to detect an event, we didn’t want a full epidemiological analysis,” Dr. St. John said. “We just wanted to know if there was an outbreak.”

Freshly dug graves at the Vila Formosa Cemetery outside Sao Paulo, Brazil, on July 20 offer a glimpse of the scale of the coronavirus pandemic to date.AFP via Getty Images

Each day, GPHIN’s algorithms sifted through more than 7,000 data points from around the world, from news reports in a multitude of languages to arcane medical data, searching for unusual patterns. Those were whittled down to five or 10 cases a day the analysts focused on.

To the untrained eye, a sudden jump in the price of hog futures in one country might not mean much. But to the analysts, it could point to an undisclosed swine flu outbreak.

The combination of machine learning and human analysis proved surprisingly effective. In 1998, GPHIN analysts noticed a pharmaceutical company in China was reporting unprecedented sales of antiviral drugs in one particular region, for no apparent reason. When they investigated further, they found China was grappling with a deadly outbreak it hadn’t told the world about – a virus that would soon be known as SARS.

At that time, though, GPHIN was still largely an experiment. When a later outbreak of SARS spread to Canada in 2003, killing 44 people, GPHIN provided early intelligence, but it wasn’t enough to avert a crisis. After that disaster, which was complicated by a lack of co-operation from China, the unit was enshrined inside the newly minted Public Health Agency and given more clout.

The idea was to arm Canada, the world and the WHO with intelligence.

“It allowed them to go back to a country and say, by the way, we know you have this outbreak,” Dr. St. John said. “And they could squeeze them into telling about it, so that the WHO could do something.”

By the mid-2000s, the unit was sending out several hundred alerts a year, flagging potential threats it detected.

When Iran was hit with a potentially catastrophic bird flu outbreak in 2005, GPHIN analysts discovered notices were being posted in the country telling locals to call a special number if they found a dead bird, though no information was provided as to why. Soon GPHIN was tracking reports of symptoms and filing alerts, which got the world’s attention. It would be six months before the Iranian government confirmed the outbreak was real.

In 2009, analysts alerted the WHO to an H1N1 swine flu pandemic in Mexico, after studying reports of unusual illnesses near Veracruz, where stores were suddenly selling out of bleach. It was only after the WHO contacted the Mexican Ministry of Health that the problem was publicly acknowledged.

The alerts worked like a smoke detector ensuring governments were at least aware of potentially urgent situations. Not every signal became a crisis, but the system never seemed to miss a big one. It was soon endorsed by the WHO as a crucial service – the “cornerstone” of Canada’s pandemic response capability, and “the foundation” of global early warning, where signals are “rapidly acted upon” and “trigger a cascade of actions” by governments, the organization said.

It was high praise.

“We showed the value of early detection,” said Abla Mawudeku, who headed up GPHIN for more than a decade and helped build it with Dr. St. John.

“Its purpose was to give guidance to decision makers.”

But as budgets shrank and government priorities shifted, GPHIN began to change. Soon, successive Canadian governments had other ideas for how it should function.

Following the 2003 SARS outbreak, the Public Health Agency was meant to be an independent medical voice inside government in the event of another deadly pandemic.KEVIN FRAYER/The Canadian Press

The system goes dark

In late 2018, analysts at GPHIN were called to a meeting where the department unveiled new plans for how the unit would operate.

GPHIN combed the world for signs of trouble, but there hadn’t been a serious pandemic in ages. Though its budget was a relatively small $2.8-million, this international focus always put it at risk for cuts.

The problem, say several past and present employees who spoke to The Globe, is that GPHIN was populated by scientists and doctors, yet largely misunderstood by government. Senior bureaucrats brought in from other departments believed its resources could be put to better use working on domestic projects, rather than far-flung threats that may never materialize.

“They would say, ‘You need to focus on Canada,’” Ms. Mawudeku said. “But the threats come from outside Canada.”

In the fall of 2018, GPHIN’s international duties were scaled back. Analysts were no longer allowed to issue alerts without first obtaining approval from senior officials, who were most often not epidemiologists.

One employee who recently left Public Health for a job outside government said that created problems because those officials often had little understanding of the scientific complexities of outbreak surveillance. This was echoed by three other internal sources who spoke with The Globe.

“All these systems were in place for early warning,” said the former employee, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak about GPHIN. “We would go to them with information and they wouldn’t understand it.”

This new requirement caused excruciating delays. Though GPHIN had been capable of flashing alerts to agencies around the world in as little as 15 minutes, it now took several days in some cases to get approval.

There was no point to an early warning system that couldn’t move fast – containment and mitigation were all about speed. Soon the alerts stopped altogether.

When the last alert was issued on May 24 last year, detailing the strange, deadly outbreak in Uganda, it took nearly nine hours for senior officials to approve it.

Meanwhile, analysts were given other tasks, working on domestic matters deemed more valuable to the government’s own initiatives. These included tracking the effects of vaping and the spread of syphilis in remote communities. Both were, arguably, worthy areas of study on their own. But the cost was high.

“Without early warning you can’t have early response. That’s where the alerts come in,” a GPHIN employee said.

Ms. Mawudeku said the new work was not what GPHIN was intended to do. “That is not early detection,” she said.

This caused disagreements inside Public Health. But friction between some of the scientists inside the department and senior officials had been building for some time.

After the 2003 SARS outbreak, the Public Health Agency was meant to be an independent medical voice inside government in the event of another deadly pandemic. But several rounds of restructuring over the years served to subjugate the role of scientists, sources told The Globe.

The Conservatives, under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, began to reshape Public Health in 2014, reducing the clout of the Chief Public Health Officer and restricting control over staffing and budgets. Senior officials were brought in from other departments, such as the Treasury Board and Border Services, to run Public Health. New layers of management were installed above the CPHO and throughout the department.

The move was billed as a way to ease the workload for Canada’s top doctor. But it amounted to a demotion of scientific voices within the department and, arguably, a way to escalate political influence in the decision-making process.

When the changes were announced, the Canadian Public Health Association, which represents public health professionals, feared the new structure would imperil the department’s ability to respond effectively in a crisis. The Liberals called the restructuring “bad news” and warned it would lead to the experts inside Public Health being stripped of their independence, allowing the government to exert control over decisions.

However, when the Liberals took power in 2015, rather than reverse the changes they once opposed, the Trudeau government kept them.

The Globe and Mail spoke with several past and present Public Health employees, some who can’t be named because they are not authorized to speak and fear punishment for doing so, who said these changes had a profound impact.

Michael Garner, an epidemiologist who spent 13 years at Public Health and was a senior science adviser before leaving in September, said scientists inside the department, including several of his colleagues still there, grew increasingly frustrated by their inability to communicate urgent public health matters to senior officials who came from elsewhere in the government.

“There’s a massive lack of understanding by the people working in the agency about the basics of health. What you present up the chain has to be dumbed down,” Mr. Garner said.

“But some of these things are complicated. Having to simplify it down just doesn’t work. As we understand from the story of the coronavirus – it’s super complicated.”

A makeshift morgue in Brooklyn, N.Y., in May includes refrigerator trucks used to store bodies of people killed by COVID-19.Brendan McDermid/Reuters

Countries that have fared better in this pandemic, including Korea, New Zealand, Thailand and Germany, moved swiftly and decisively in the earliest days of the virus.

“How do you convince someone that acting to prevent something is worth it?” Mr. Garner said. “It’s really hard, and it’s even harder when you’re dealing with people who aren’t scientists and really just want things to remain calm.”

Another former employee, who could not be named because he still works in Ottawa and fears punishment for speaking publicly, corroborated Mr. Garner’s account.

“What kind of happened over the last four or five years is PHAC became very bureaucratic,” the employee said. “So instead of these PhDs and epidemiologists who knew what was going on, you would go to managers with information and they wouldn’t necessarily understand it.”

That disconnect led to fundamental changes at GPHIN. With the alert system now curtailed, its international surveillance capacity has also suffered greatly, the employee said.

It has been difficult to get an answer from the government as to why GPHIN has effectively gone silent. When asked by The Globe why it stopped issuing international alerts for disease outbreaks and other public health threats, Public Health at first denied they had stopped.

“GPHIN has not ceased issuing alerts,” Public Health said in an emailed statement.

It was only when The Globe informed the government that it had obtained extensive records showing no international alerts have been sent in more than a year – including immediately before and during a major pandemic – that the government changed its message.

No alerts had been issued, a Public Health spokeswoman acknowledged, but that didn’t mean alerts had stopped. They just weren’t being made any more.

“The approval level for an alert from the Global Public Health Intelligence Network was raised from the analyst level to senior management,” Public Health said in an e-mail statement.

This was done “to ensure appropriate awareness of, and response to, any emerging issue.”

But rather than improve the system, it merely shuttered it.

Final authorization for alerts now rests with the vice-president of the Health Security Infrastructure Branch, Sally Thornton. The Globe requested an interview with Ms. Thornton, who came to the department from positions at the Treasury Board and Privy Council and has a background in business and law, to explain the reasoning for the move.

The request was declined twice.

In a statement, Public Health said GPHIN’s newfound domestic focus is an example of “subject-specific surveillance” but that international detection was still its “primary role.”

Even though the department’s own records show that no alerts have been issued since last spring, despite more than 1,500 being made over the past decade, Public Health said GPHIN’s role “remains unchanged.”

Yet, staff inside the department said international surveillance is no longer the priority.

“By the time Wuhan arrived,” said one analyst, who is not cleared to speak publicly, “it was understood surveillance was to focus on Canada.”

Chileans in Santiago bury a loved one at the General Cemetery in June.AFP via Getty Images

‘We knew we were in trouble’

Scientists now believe China was keeping the outbreak quiet for several weeks, possibly longer, by the time word leaked to the international community.

The first indication the rest of the world had of a problem came on the night of Dec. 30.

Just after 8:00 p.m. eastern time that evening, Marjorie Pollack, a veteran epidemiologist who helps run ProMed, a New York-based health network, was sitting down to watch a movie with her husband when an e-mail lit up her phone. It was from a contact in Taiwan.

“This is being passed around the internet here,” the man said. “Not sure if you have people there who might know more.”

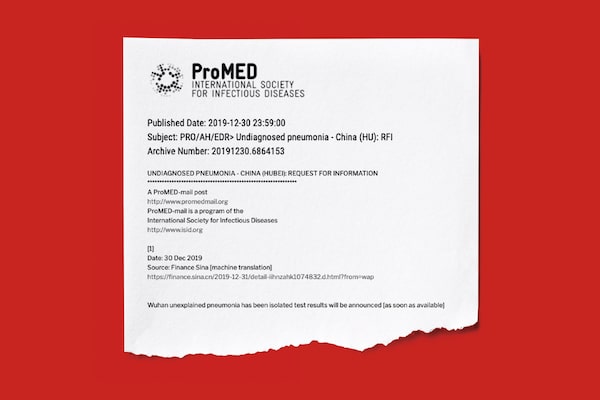

An alert sent by ProMed on Dec. 30 was the first international alert of the novel coronavirus outbreak. (Click to enlarge)PHOTO ILLUSTRATION: THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Attached was a picture of a bulletin posted inside a hospital in Wuhan, warning doctors there of a rapidly spreading “Pneumonia of unknown cause.” The photo had begun circulating on Chinese social media a few hours earlier.

Dr. Pollack’s stomach churned. Unknown respiratory illnesses weren’t typical. Those were trigger words.

“People say you can’t rely on gut. Only the gut has been there before,” Dr. Pollack said. “I was around for SARS, and this smelled like SARS.”

She scanned her contacts in the early-detection world. GPHIN, the Canadian surveillance operation that had a strong reputation globally – and often fed data into ProMed – was reporting nothing. That was odd. But there was no time to dwell on it.

Dr. Pollack began reaching out to contacts in Asia, trying to confirm the warning, which was now finding its way into news reports in China. That evening, just before midnight, ProMed and a blog called Flu Tracker – which does similar work, gathering mostly unverified crowd-sourced information – delivered the first glimpse to the West of what would soon become the COVID-19 pandemic.

Back in Ottawa that night, GPHIN’s offices – the victim of shifting priorities – sat mostly idle. Any indirect signals that might have revealed the outbreak at its most embryonic stage before then had been missed.

The next morning, 80,000 doctors who subscribe to ProMed, many in Canada, awoke to news of the threat. The Chinese government, confronted with photos of bulletins posted at its own hospitals, soon confirmed the outbreak to the WHO – though no one outside China knew for sure how long the virus had been festering.

“Did we know we were dealing with a pandemic? No,” Dr. Pollack said. “But we knew we were in trouble.”

If other countries were caught flat-footed that night, Canada was further behind. When GPHIN analysts arrived at work on Dec. 31, they didn’t have approval to begin issuing alerts for whatever intelligence they could gather on the fast-moving situation.

This included alerts that would go to top decision makers in the federal government, the provinces, health regions across the country, and to nations and organizations around the world that could be spurred into action by new information.

During other potentially deadly outbreaks that never reached COVID-19 levels, GPHIN rapidly issued dozens of such alerts informing the government and the WHO of the latest intelligence on how the disease was spreading, how hospitals and cities were affected, and who was at risk. Urgency was the key.

But as the hours turned into days, GPHIN was silent.

This silence appears to contravene the federal government’s own stated procedures. The Globe obtained a copy of Public Health’s internal decision tree, which governs when GPHIN is required to start tracking and alerting significant developments involving potential health threats – both for Canadian citizens and under its commitment to International Health Regulations.

The decision tree focuses on key questions designed to assess risk: Is the public health impact of the event serious? Is it highly contagious? Is it located in an area with high population density? Is the event unusual or unexpected? Is there a significant risk of international spread?

If at least two or three of those answers are yes, GPHIN is required to act.

HOW GPHIN’S ALERT SYSTEM IS

SUPPOSED TO WORK

DOES THE EVENT WARRANT AN ALERT UNDER INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS?

An event involving the following diseases shall always lead to utilization of the algorithm, because they have demonstrated the ability to cause serius public health impact and to spread rapidly internationally:

- Cholera

- Pneumonic plague

- Yellow fever

- Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Ebola, Lassa, Marburg)

- West Nile fever

- Other diseases that are of special national or regional concern, e.g. dengue fever, Rift Valley fever, and meningococcal disease.

OR

Any event of potential international public health concern, including those of unknown causes or sources and those involving other events or diseases than those listed in the boxes above and below shall lead to utlization of the algorithm

OR

A case of the following diseases is unusual or unexpected and may have serious public health impact, and thus shall be notified:

- Smallpox

- Poliomyelitis due to wild-type poliovirus

- Human influenza caused by a new subtype

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

IS THE PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF THE EVENT SERIOUS?

YES

NO

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

YES

NO

YES

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTER-

NATIONAL/

REGIONAL EVENT?

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTER-

NATIONAL/

REGIONAL EVENT?

YES

YES

NO

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL OR TRADE RESTRICTION?

NO

YES

NOT NOTIFIED AT THIS STAGE, REASSESS WHEN MORE INFORMATION BECOMES

AVAILABLE.

GPHIN ALERT UNDER INTER-

NATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY OF CANADA DOCUMENTS

HOW GPHIN’S ALERT SYSTEM IS

SUPPOSED TO WORK

DOES THE EVENT WARRANT AN ALERT UNDER INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS?

An event involving the following diseases shall always lead to utilization of the algorithm, because they have demonstrated the ability to cause serius public health impact and to spread rapidly internationally:

- Cholera

- Pneumonic plague

- Yellow fever

- Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Ebola, Lassa, Marburg)

- West Nile fever

- Other diseases that are of special national or regional concern, e.g. dengue fever, Rift Valley fever, and meningococcal disease.

OR

Any event of potential international public health concern, including those of unknown causes or sources and those involving other events or diseases than those listed in the boxes above and below shall lead to utlization of the algorithm

OR

A case of the following diseases is unusual or unexpected and may have serious public health impact, and thus shall be notified:

- Smallpox

- Poliomyelitis due to wild-type poliovirus

- Human influenza caused by a new subtype

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

IS THE PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF THE EVENT SERIOUS?

YES

NO

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

YES

NO

YES

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTER-

NATIONAL/

REGIONAL EVENT?

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTER-

NATIONAL/

REGIONAL EVENT?

YES

YES

NO

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL OR TRADE RESTRICTION?

NO

YES

NOT NOTIFIED AT THIS STAGE, REASSESS WHEN MORE INFORMATION BECOMES

AVAILABLE.

GPHIN ALERT UNDER INTER-

NATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY OF CANADA DOCUMENTS

HOW GPHIN’S ALERT SYSTEM IS SUPPOSED TO WORK

DOES THE EVENT WARRANT AN ALERT UNDER INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS?

A case of the following diseases is unusual or unexpected and may have serious public health impact, and thus shall be notified:

- Smallpox

- Poliomyelitis due to wild-type poliovirus

- Human influenza caused by a new subtype

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Any event of potential international public health concern, including those of unknown causes or sources and those involving other events or diseases than those listed in the box on the left and the box on the right shall lead to utlization of the algorithm

An event involving the following diseases shall always lead to utilization of the algorithm, because they have demonstrated the ability to cause serius public health impact and to spread rapidly internationally:

- Cholera

- Pneumonic plague

- Yellow fever

- Viral hemorrhagic fevers (Ebola, Lassa, Marburg)

- West Nile fever

- Other diseases that are of special national or regional concern, e.g. dengue fever, Rift Valley fever, and meningococcal disease.

OR

OR

IS THE PUBLIC HEALTH IMPACT OF THE EVENT SERIOUS?

YES

NO

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

IS THE EVENT UNUSUAL OR UNEXPECTED?

YES

NO

YES

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTERNATIONAL/REGIONAL EVENT?

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTERNATIONAL/REGIONAL EVENT?

YES

YES

NO

NO

IS THERE A SIGNIFICANT RISK OF INTER-

NATIONAL TRAVEL OR TRADE RESTRICTION?

NO

YES

NOT NOTIFIED AT THIS STAGE, REASSESS WHEN MORE INFORMATION BECOMES AVAILABLE.

GPHIN ALERT UNDER INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: PUBLIC HEALTH AGENCY OF CANADA DOCUMENTS

Further, the document states that outbreaks involving “SARS” or “human influenza caused by a new subtype” should prompt continuing international alerts. Yet, GPHIN did not send any.

Surveillance that uncovers new developments – including revelations that health care workers are getting sick, or if asymptomatic transmission becomes evident – also require further investigation and alerts. But GPHIN’s system stayed quiet.

The early signals that would have been percolating in Wuhan were exactly the kinds of clues GPHIN was designed to detect and magnify.

But Dr. Pollack at ProMed wasn’t the only one confused as to where Canada’s early warning system went in a crisis.

Reached at his home near Ottawa, where he is now retired, Dr. St. John – founder of the system – said he was also puzzled.

“I wondered where GPHIN was,” he said.

Families hold a candlelight vigil on June 15 outside the Orchard Villa long-term care home in Pickering, Ont., where 78 residents died from COVID-19.Melissa Tait/The Globe and Mail

Items were removed from reports

Without the ability to sound the alarm internationally, one of GPHIN’s key roles was to channel intelligence within the federal government, so that policy makers could speed up their decision making.

In early January, with dire news of the outbreak starting to emanate from China, GPHIN analysts began preparing daily reports on the Wuhan situation.

Using whatever information they could glean from Chinese media sources, internet chatter throughout Asia, testimonials from doctors on the ground and data on case numbers, GPHIN began producing a daily sketch of the evolving crisis.

The situation in Wuhan was growing dangerously complex. Though Beijing was telling the world there was no reason to halt flights from China, close airports, tighten borders or curtail economic activity, the government there had already started shutting down cities and restricting travel. By all accounts, the situation was worse than Beijing was letting on.

But as GPHIN analysts filed their internal reports, they began to face pushback within the department. They were told to focus their efforts on official statements, such as data from the Chinese government and the WHO. Other sources of intelligence were just “rumours,” one analyst was told. “They wanted the report restricted to only official information.”

This created a weakness in trying to assess the situation accurately, current and former employees say.

Later, after receiving pushback that their reports were becoming too detailed and contained too much unofficial data, the analysts realized not all of their research was making it up the chain of command inside the department.

At a meeting of senior officials in the first few weeks of the outbreak, a Public Health director was asked why GPHIN’s internal reports had missed crucial developments that were now being widely reported in news around the world: that human-to-human transmission of the virus had been detected.

Confronted about the omission, the analysts were confused. That information had in fact been discussed in earlier reports, before it was widely known – and before the documents were sent up the chain.

“Items on Wuhan and transmission were mentioned,” said the employee. But those items “were removed,” the person said.

At that moment, the analysts couldn’t be sure what information they were gathering was being conveyed up through the department.

Asked why such material would be removed from the analysts’ reports, Public Health would not agree to an interview, but responded in a statement: “The premise of the question is not clear; senior management at PHAC have been fully engaged and briefed on the issue since the first report of an undiagnosed pneumonia in Wuhan emerged on December 31, 2019.”

However, such signals were exactly the kind of information GPHIN was created to detect, so that the government could understand the urgency, and move quickly.

“A week or even a few days makes a huge difference,” one GPHIN employee said. “Our basic reason for existing was to get information to the decision makers so that this wouldn’t happen.”

The body of a COVID-19 victim is prepared for cremation in New Delhi on June 5. Like elsewhere in the world, risks associated with the coronavirus pandemic have made honouring the dead in India a hurried affair, largely devoid of the rituals that give it meaning for mourners.Manish Swarup/The Associated Press

We weren’t paying attention

Throughout January, February and into March, the government believed the outbreak posed little risk to Canada.

Even as disturbing signals began to emerge from China, and soon Italy, Ottawa’s position did not waver.

On Jan. 15, the Public Health Agency produced a document known as a Situation Report that stated the risk the virus posed to Canada was “Low.”

The SitReps, as they are known, are internal documents distributed by the Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response, providing a snapshot of an evolving event and an assessment of its urgency. The reports draw input from a variety of federal sources, GPHIN among them.

The government’s risk assessments for COVID-19 were based on several factors, including the likelihood of the virus spreading internationally, and whether certain types of transmission were known to be occurring – such as person-to-person and asymptomatic spread.

However, despite the government’s determination that the risk to Canada was low, the Jan. 15 report contained a key detail that, perhaps, should have raised more concern than it did: The wife of a man working at the Wuhan market where the outbreak is believed to have originated had fallen ill, even though she had no exposure to the market. “Potential person-to-person transmission has been identified,” the SitRep said.

But several days later, Health Minister Patty Hajdu was given speaking notes that downplayed those same risks. Canadians were told to wash their hands often, but wearing masks was not necessary. “Based on the information that we have,” the notes said, under the title “Minister’s Messages,” there was “no clear evidence that this virus is easily transmitted between people. However, it is possible there may be limited human-to-human spread.”

Inside the department, the analysts and other scientists at Public Health were growing frustrated with a bureaucracy that didn’t see the value in interpreting the troubling signals coming from China.

“The Agency thought it was China’s problem and that, because they had [dealt with] SARS, they were ready,” the GPHIN analyst said.

By late January, the signals were growing louder. Chinese health workers were falling ill; crews were rushing to build an emergency hospital; high-level political meetings were abruptly cancelled; and the mayor of Wuhan admitted the government dragged its feet on releasing data about the outbreak. Talk of overflowing hospitals and mounting deaths grew louder online.

On Jan. 24 in Wuhan, rapid construction began on a hospital dedicated to treating patients with coronavirus.REUTERS

These were hints of an unusual problem. Yet with the situation evolving rapidly, Canada revisited its risk assessment in a Jan. 24 Situation Report and said the threat “remains low.”

That risk assessment grew even more conspicuous just four days later, on Jan. 28, when the WHO changed course and declared the risk to the world was “High,” urging countries to prepare.

But Canada didn’t budge. Two days later, on Jan. 30, Canada said the risk “remains low.”

Given his experience, Mr. Garner calls it “peculiar” that Canada didn’t elevate its concern level at that point. “They would have known that the WHO had raised it,” he said.

However, a spokeswoman for Public Health said Canada didn’t have significant levels of COVID-19 at that time, so there was no need to escalate the concern level – despite the fact that the virus was already spreading rapidly around the world.

“The public health risk assessment reported was based on the risk of COVID-19 within Canada at that time,” the spokeswoman said. “There was no evidence that COVID-19 was circulating within the population.”

A month later, the government remained confident. On Feb. 26, Deputy Chief Public Health Officer Howard Njoo told the House of Commons Health Committee the situation was under control. “We have contained the virus,” he said, noting there were just a dozen cases in Canada.

Yet clues the outbreak was spreading aggressively were there. By March, the WHO reported 40 per cent of cases tracked outside China “do not have a known site of transmission,” meaning the victims had no explanation as to how they contracted the virus.

On March 11, with cases in 114 countries, the WHO formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic. Even this did not immediately cause Canada to rethink its position.

It wouldn’t be until March 16 – five days later – that Canada finally decided to raise its own risk assessment for Canada from “Low” to “High,” and urged Canadians to begin social distancing.

The catalyst for that decision, Public Health told The Globe in a statement, was evidence of human-to-human transmission in Canada. “The appearance of community spread of COVID-19 within the Canadian population prompted an increase in the level of risk,” the statement said.

But that was something that had been signalled for months in the government’s own intelligence reports – at least as far back as the Jan. 15 Situation Report.

Now, more drastic measures were needed. The country was going into lockdown. Businesses would shutter, the economy would grind to a halt, jobs would be lost and long-term care homes would be overrun. Thousands of people would die.

“The time has come for all Canadians to do what’s necessary to help us get through this pandemic,” Public Health Agency president Tina Namiesniowski told the House of Commons health committee on March 31.

But in the months prior, international signals were disregarded or missed, and there was no such urgency.

“The thing that leaps out at me is that I don’t see anyone within government raising serious alarm bells,” said Wesley Wark, an adjunct professor at the University of Ottawa who is a specialist in international affairs and intelligence gathering. “The real failure is that we weren’t paying enough attention to what was actually going on in China.

“This is where GPHIN was meant to perform such an important role, as the collector and filter for decision making.”

Signals that a pandemic could spread globally in 2020 were there even as New Year’s Eve fireworks were exploding over cities like Singapore.EDGAR SU/Reuters

Consequences

As much of the world beyond China popped Champagne on New Year’s Eve, blissfully unaware of what lay ahead in 2020, Dr. Pollack knew the e-mail from Taiwan was likely a harbinger of a crisis to come.

“I could have been wrong,” she said. “I wish I was.”

Early detection is as much an art as it is a science. The disease is hiding, but the signals are detectable. Acting quickly can have a big impact on the outcome.

With COVID-19, the signals began small, but grew louder.

“We all had enough warning,” she said. “We saw what happened in China, in Italy.”

Dr. St. John agrees. “The signal was there,” he said.

However, few people outside GPHIN knew Canada’s early warning alert system had effectively stopped working, just when it was needed most.

When Ms. Thornton, the vice-president in charge of the alerts, appeared before a House of Commons committee in May to face questions about Canada’s handling of the pandemic, she was asked how the government had tracked the spread of the virus.

Ms. Thornton referenced GPHIN and the work it did. Though she made no mention that GPHIN had not issued a single alert in the previous 12 months.

Nor did she mention that analysts had been assigned to other work, or that GPHIN had not sounded any further alarms on COVID-19 developments after the outbreak became known – even though the department’s own guidelines required as much.

As far as the committee knew, Canada’s surveillance system had been operating as it always had.

It’s not easy to know the consequences of such decisions, but Mr. Garner, the former senior science adviser at Public Health, says he believes Canada’s early response to the outbreak – which has been criticized for being slow and disorganized – was a product of the many changes he saw made to the department.

Those changes helped move Public Health’s focus away from science, he said, which slowed down its ability to react effectively – and with maximum urgency.

“All of these things have tragically come home to roost,” Mr. Garner said.

“Not to be overdramatic, but Canadians have died because of this.”

Sign up for the Coronavirus Update newsletter to read the day’s essential coronavirus news, features and explainers written by Globe reporters and editors.

Grant Robertson

Grant Robertson