Illustration by Sam Island

Welcome to the third week of the Retire Rich Roadmap newsletter, which is all about building a lifetime of wealth to set you up for a comfortable retirement – and maybe even have some left over to pass along to later generations. (Week one and week two can be found here, in case you missed them. Was this forwarded to you? Sign up for the full course here.)

First there are the basics. Do you have an RRSP? How about a TFSA? Or a non-registered portfolio? What about alternative investments? What options are available for diversification?

Let’s walk through what should be the pillars of your investment portfolio, some lesser-known options and long-term approaches to wealth building in general.

Illustration by Sam Island

Registered vs. Non-registered

Registered Retirement Savings Plans are the key element of most Canadians’ retirement investments because the government offers tax incentives for us to make contributions to those accounts. Your RRSP can hold a variety of qualified investments including stocks, bonds, guaranteed investment certificates (GICs), mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and cash. Precious metals and commodities cannot be held in RRSPs. They can protect investments from tax up until you reach the age of 71. At that point, they “mature,” and must be withdrawn and transferred to a registered retirement income fund (RRIF) or used to buy an annuity.

Tax-free savings accounts act as the sidekick to RRSPs and offer some unique benefits and more flexibility. Unlike an RRSP, the TFSA has no associated tax deduction, meaning contributing to it will not help you pay less in taxes right away. However, while RRSP withdrawals are taxable, money you take out of your TFSA is not subject to taxation. For building wealth, they are better viewed as investment accounts, rather than traditional savings accounts which pay minimal interest. TFSAs can offer better “bang for the buck” in tax benefits for students or those with low taxable earnings. For 2023, the TFSA contribution limit is $6,500 and, for those who have not yet set up a TFSA, you can deposit a total of $88,000 if you were over 18 in 2009.

To assist with soaring education costs, Ottawa also created the Registered Education Savings Plan for parents and caregivers to put away money. Available for each child up to the age of 17, RESPs allow for tax-free growth of savings. In addition, the federal government will match up to 20 per cent of contributions through the Canada Education Savings Grant. (For $2,500 invested annually, the government will contribute the $500 maximum). RESPs can be eligible for additional grants through the Canada Learning Bond and provincial programs.

Beyond registered plans, investors should consider making non-registered investment accounts part of their retirement portfolio. Non-registered accounts are not tax-deductible, but funds in those accounts can be invested in places with their own tax benefits, such as Canadian dividend-paying stocks. Highly taxed interest-paying investments – such as bonds – should be put in registered accounts along with potentially high-growth stocks and ETFs.

Because you are in the wealth-creation or nest egg-building business, you want to make your registered investments regular, automatic, and as large as possible.

If your employer offers a group plan with matching contributions, increase your annual contributions to get the maximum match from the company. Your work is offering free money for your retirement – take it. Make sure that when your salary goes up, you increase your RRSP contribution, especially if it comes with employer matching. Another simple way to juice your RRSP growth is to make contributions at the beginning of the tax year rather than during the mad tax year end like most Canadians. This strategy produces years’ worth of extra growth by getting that money invested and growing earlier.

Pay attention to investment costs and complexity. Do you own a multitude of funds that all hold the same equities and bonds and carry return-eating fees? It might make sense to hold a smaller number of ETFs that offer better diversification, less duplication, and lower fees.

Illustration by Sam Island

Real estate

Most Canadians are heavily exposed to real estate as an investment if they own a home or condo, however it’s really best considered as a long-term opportunity.

Given the skyrocketing home prices, many Canadians see owning their own home as a great way to also build a nest egg. But financial planners advise against treating a home or condo as a de facto retirement savings account. It can be time consuming – and costly – to sell a home when the time comes. Further, many seniors have been struggling to downsize because of a lack of suitable retirement housing in Canada. By selling your home to address a cash crunch, you create a new problem: Where to live?

That said, it’s hard to deny that home ownership does offer an advantage when it comes to retirement savings. A recent study by Mercer Canada found that people who rent through their careers must save 50 per cent more than homeowners to have a sufficient retirement income. It’s entirely possible to make that happen, as this article explains. It’s also possible to generate retirement income from your home without selling it through options like a Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) or reverse mortgage. (For more on these options, see this story by Ana Pereira.)

But what about investing in real estate beyond your family abode? The hot market has made it into an attractive option. Real estate falls under the alternative investment class along with private equity and debt. Compared with stocks, bonds, and funds such as ETFs, real estate tends to be a more complex investment and is less liquid, but offers diversification and potentially higher returns in the form of steady rental income and asset appreciation.

Beyond real estate, other alternative investments (not stocks, bonds, or cash) include private equity and venture capital (investments in companies not publicly traded), hedge funds, and real assets such as commodities, precious metals, land, and equipment.

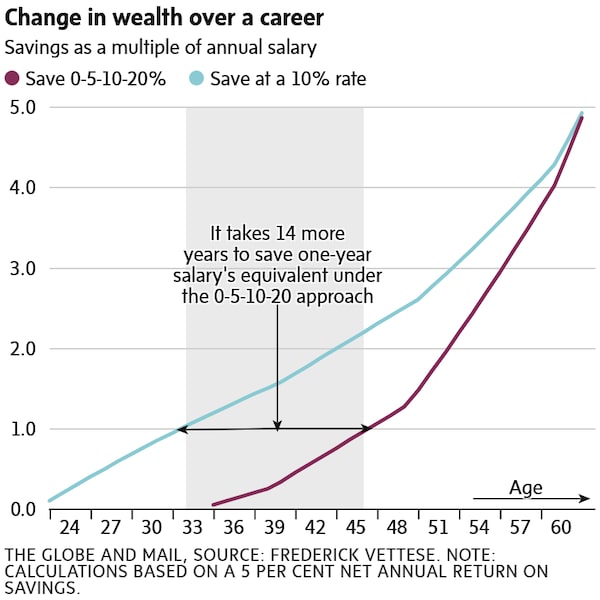

A graphic look

The Globe and Mail

Consider this hypothetical situation for Jack, writes Frederick Vettese, former chief actuary of Morneau Shepell and author of Retirement Income for Life. Jack’s earnings triple in real terms over a 40-year career and he finishes with pay that is double the national average. If Jack retires at 63, he should aim for retirement savings that are at least five times his final year’s pay.

The chart shows two ways to get there. Jack could save 10 per cent of his pay every year for 40 years or he could wait until age 35 to start saving and then save 5 per cent from 35 to 39, 10 per cent in his 40s and then 20 per cent from 50 until retirement.

Saving a flat 10 per cent is hard to do in Jack’s early working years but it is less risky if he is laid off or retires earlier than planned. Saving based on the 0-5-10-20 schedule fits in better with how Jack’s disposable income increases throughout his career but it’s not for the faint of heart. Note: it takes Jack 14 more years to save one times salary under the 0-5-10-20 approach.

Try this at home

· Regardless of your age, determine how much you have saved currently for retirement.

· Sit down with your investment adviser to see whether your investment trajectory is going to achieve your goals.

· If you do not have an investment adviser, consider hiring a fee-only adviser for a status check.