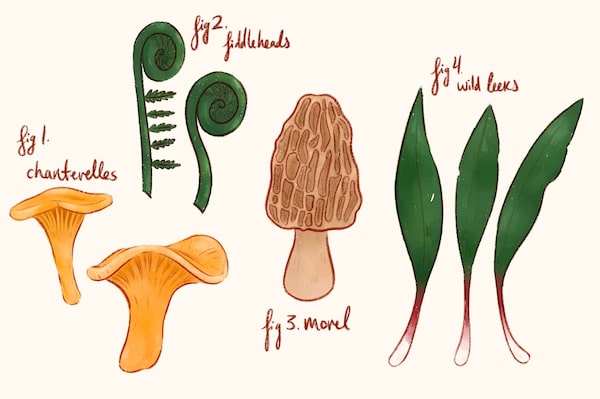

Foraging for plants like mushrooms and fiddlehead ferns is becoming a popular new hobby.Gabrielle Drolet

There’s a word popping up all over the menus at the trendiest restaurants in town: “wild.” Wild mushrooms, wild leeks, wild fiddleheads, wild seaweed.

Plants plucked straight from their natural habitats have made their way onto our plates, with many chefs and home cooks seeing their local woodlands, fields and bodies of water through a new, plentiful lens.

Why the sudden fondness for wild ingredients? “I think basically people are paying more attention to what they’re putting in their bodies,” says Tofino-based chef Paul Moran, whose family has been foraging for five generations.

“There’s definitely been a shift toward health and nutrition recently, and wild foods offer some of the best nutrition and health benefits. And more recently, with COVID-19, people have been spending more time outdoors, and that has a lot to do with it too.”

In 2019, Moran impressed the judges on Top Chef Canada with, among other things, his stuffed foraged morels. In fact, he prepared them three times over the course of the show, which he went on to win.

Expert forager Peter Blush leads groups in search of spring's hottest menu item, fiddleheads.Terry Manzo

He now shares his exceptional knowledge and cooking through Wild Origins, a company he founded that caters events and runs “forage and feast adventures” where he brings guests on foraging tours that end with a multi-course gourmet meal prepped by Moran incorporating the day’s bounty.

“Our horizons have definitely broadened,” he says. “There used to be, say, wild mushrooms on menus, but now some of the top restaurants are making sure they have wild plants and seaweeds on menus, which wasn’t necessarily the case 15 or 20 years ago.” Wild garlic, it seems, is 2022′s answer to 2015′s quinoa, or 2018′s kefir.

Expert forager Peter Blush is also appreciating the uptick in interest. Through his company, Puck’s Plenty, in Stratford, Ont., he’s been sharing his passion for the wild foods of Southwestern Ontario with both curious newbies and more seasoned foragers since 2010.

'The act of foraging and getting out there and living an active lifestyle is super healthy,' says Moran.Peter Blush

“All our events are sold out – I don’t even advertise anymore,” he says. “As far as culinary movements go, people are interested in the fact that ‘Hey, right out there in the woods, we can go and harvest food that actually tastes really good.’ They want something different when it comes to taste, and that can set them on the road to foraging.”

Many of Blush’s guests really dig into foraging after a tour. “A common comment I get is ‘From now on, I’ll never go into the forest and look at things like I used to,’” he says.

One of those converts is Mississauga-based architect Jenny Chau, who attended her first Puck’s Plenty tour three years ago and has been keen on discovering the fruits of the forest ever since.

“It’s a connection to nature,” she says. “Before, we would go on hikes and go, ‘Oh, interesting plants,’ but we weren’t looking for [edible ones]. Now we go hiking and we look for mushrooms; we don’t necessarily want to pick them because we’re not knowledgeable enough yet, but it just makes your eyes more attuned to what’s available.”

Chau was long interested in learning about foraging but was wary about going out on her own and picking something inedible. (“It’s not a pleasant ride through your digestive tract,” Blush says drily of eating the wrong plants.) But now that she’s had a solid intro, she’s building up to foraging independently.

“It’s very relaxing. You don’t rush – you just have to observe [and determine] what’s good and what’s not. And when you pick some things, you feel very accomplished,” she adds.

Top Chef Canada winner Paul Moran is a fifth generation forager who now uses his expertise to guide groups in search of wild ingredients.Dominic Hall

Both Blush and Moran encourage anyone who’s interested to join foraging groups on social media or go out with a knowledgeable guide the first couple of times. “Knowing what to forage and how to forage is really important,” say Blush. “You have to know what’s poisonous and what’s not. For example, wild leeks and lily of the valley look similar, but lily of the valley is poisonous.”

Blush stresses that the most important consideration is sustainability: knowing how to pick things without depleting the growth in that area. “Wild leeks grow in beds, and if you take the entire bed, they’re not going to come back,” he says by way of example. “So you don’t take a lot and you take from the middle of the bed because you want it to keep expanding.”

Ultimately, foraging isn’t going to go very far in supplementing people’s diets – but it’s a good exercise in learning about our natural environment and an opportunity to enjoy wild foods. “They’re a nice accompaniment for people to incorporate into their diet from time to time or when they’re in season,” says Moran. Foraged foods are also a way for people to eat more sustainably, a “hyper local” menu with no guilt-inducing carbon footprint (unless, of course, you drove to that patch in the woods – and even then, that’s nothing on the refrigerated miles logged by most other produce).

“Wild foods in general have lots of micronutrients that you don’t get in any other foods, and the act of foraging and getting out there and living an active lifestyle is super healthy,” says Moran.

A trend we can all go wild for.

Sign up for The Globe’s arts and lifestyle newsletters for more news, columns and advice in your inbox.