She grew up in a log house without electricity or running water, at the end of a long, twisting road in the backcountry of southwestern Alberta.

In the mid-1950s, Beverley Gietz was 12, and living much as children did 50 years earlier.

An outhouse stood deep in the back of the yard. For light, her family had kerosene lamps. For baths, the youngest of her four siblings went first. A little hot water was added for the next, and the next, all the way up to the oldest, Beverley, and then her mother and father.

She knew how to ride a horse. Her home was where the foothills met the Rockies; for fun, she played in the mountains and read books. Grizzly bears, cougar, elk and deer roamed nearby. Her father, Ernest, was a rancher, a hunter, an owner of a small sawmill. Her mother, Eleanora, did the bookkeeping. Her parents were evangelical Lutherans. No drinking or dancing, no playing cards, no smoking.

These were the years in pioneer country that helped form the country's longest-serving Supreme Court chief justice – the judge who put her stamp on some of the most pressing legal and social questions of 21st-century Canada. Those early years bred in her that quality that defined her as a judge: a "fierce independence," in the words of Warren Winkler, who grew up in the area at the same time, and went on to become chief justice of Ontario.

She showed that independence early. The log house was so remote and the unpaved road so treacherous, that she took Grade 7 at home, by correspondence – and finished an entire academic year before December.

When rural electricity arrived soon after that, 13-year-old Beverley designed a big new wooden house, which her father then built from the timber he milled on his property. "Beverley's room seemed like a scene from the movie Heidi," her childhood friend Diana Reed, who still lives on a ranch in the area, recalled several years ago. "I remember being with her and looking out the window at the mountains and the stars."

Even so, Beverley Gietz was impatient to leave. She could have waited until Grade 9, when she would stay at a dormitory near the school in Pincher Creek, with others from the countryside. Instead, she chose to leave home for Grade 8, boarding with a family in town. She had a sense that she had a dream to follow.

Ultimately, her achievements were remarkable. She would go on to help shape Canadians' fundamental rights as much as any judge in the country's history, from the legalization of assisted dying, to a huge expansion of Indigenous rights, to a rebalancing of how police and the legal system treat people accused of crimes.

Along the way, her independence and that of the institution she led, and shaped, would put her on an unprecedented collision course with a sitting prime minister from the Conservative Party, whose strongest supporters were to be found in rural, religious areas like the one in which Ms. McLachlin had grown up.

The legal architecture she helped put in place, built in increments over decades, will not easily be torn down by future jurists.

And yet, Beverley McLachlin remains unknown, in human terms, to most Canadians. And an enigma, in legal terms, even to many in the legal community.

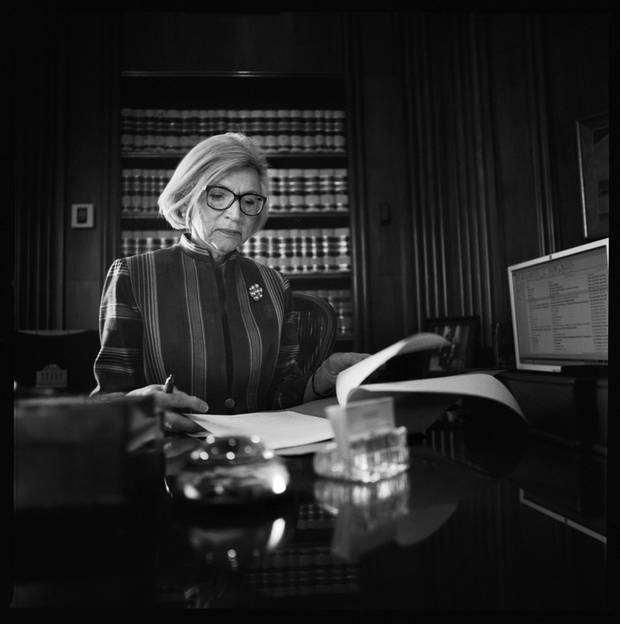

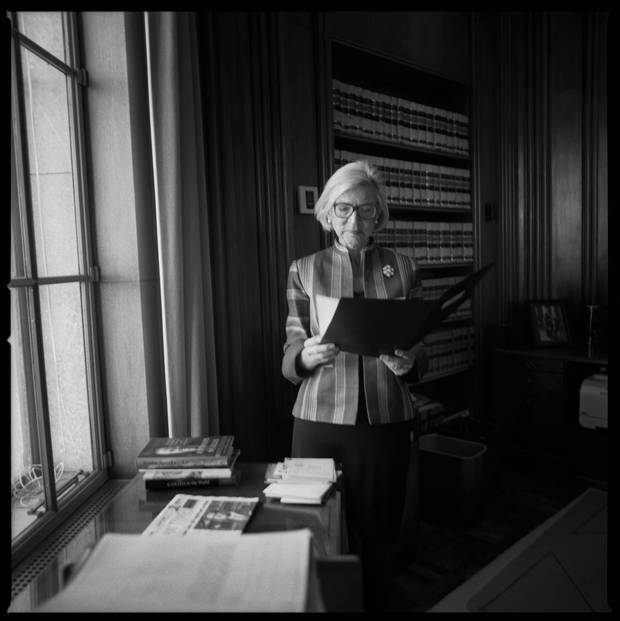

Looking back at her youth, Beverley McLachlin says she had ‘a very strong sense that it was important to, as Joseph Campbell would put it, follow your bliss.’

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

H

er drive was unstoppable – a reaction, in no small part, to her mother's lost dreams.

Eleanora Gietz had wanted a university education and to write children's books, but then her own mother took sick and she had to nurse her rather than go to school. And then, she had a family of her own.

"Life overtook her," Chief Justice McLachlin said during a 50-minute interview in her Supreme Court office last month.

It is four days before her retirement. She is relaxed and open. At times she laughs loudly.

"I identified very early with her aspirations, and her disappointment. I think at some subconscious level, it made me very determined that that would not happen to me.

"And I had a very strong sense that it was important to, as Joseph Campbell would put it, follow your bliss. Not in any trivial sense, but in a sense of where life seemed to be leading you, what you felt you might have a vocation to do. I didn't know what it was, but I knew, as a teenager, I would try to find it."

She knew she would go to university – but didn't know how she would pay for it. Then she won "three or four" scholarships to the University of Alberta; she left home and obtained an undergraduate degree in philosophy. As if in a hurry to find where life was leading her, she studied law at the same time as she did her master's in philosophy. Her peers were in awe of her intellect and the way she carried herself.

"She had a presence," recalls Ellen Picard, one of a handful of women studying law at the University of Alberta at the same time as Ms. McLachlin. (Ms. Picard became a judge on the province's Court of Appeal, from which she has now retired.)

Those were pioneering times for women in law. "Some people viewed women as an oddity," Ms. McLachlin told the Allard School of Law History Project at the University of British Columbia last year. "There were a lot of sexist comments. I just learned to ignore them. That was the other person's problem. I refused to make myself a victim."

When she graduated in 1968, Ms. McLachlin won the law school's gold medal. For the next half-dozen years, she practised law, mainly civil litigation – first in Edmonton, then in the northeastern B.C. town of Fort St. John and, finally, in Vancouver.

Leaving her practice behind in 1974, she became a tenured professor at UBC, teaching the law of evidence, and co-writing several legal textbooks. In April, 1981, she left the academy to become a judge on the B.C. County Court, a provincially appointed body.

Neither of her parents witnessed the moment she joined the bench. Both died relatively young. Her mother, born in 1920, passed away in 1972; her father died in 1977, at 62.

She stayed at the County Court only through the summer. In September, the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau appointed her to the B.C. Supreme Court, six months before the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms took effect.

Over the next four years, the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney would appoint her to three different jobs. First was the B.C. Court of Appeal, the province's highest court, in 1985. Then, in 1988, back down she returned to the B.C. Supreme Court – now, as chief justice.

A few days later, her husband of 20 years, Roderick McLachlin, a logger and environmental consultant with a PhD in biology, died after a 10-month struggle with cancer of the mouth. Shortly afterward, Chief Justice McLachlin was scheduled to give a speech; she went ahead with it. Life was not going to overtake her.

And tragedy would not hold her back. Six months after Roderick's death, Mr. Mulroney called to offer her a spot on the Supreme Court of Canada.

"She was very strongly recommended to me by John Fraser," Mr. Mulroney told The Globe and Mail for this story. Mr. Fraser was the minister of fisheries. More importantly, he was the political minister from B.C. in the federal cabinet, influential in the appointment of judges. "John," Mr. Mulroney says, "was a guy whose opinions I respected a great deal."

Chief Justice McLachlin was in Australia with her son, Angus, when she got the call. He was just 12 years old – and told her to take the job. She left him in the care of her sister, Judy, in Vancouver for the remainder of the school year while she moved to Ottawa for her April start.

She was 45, and had found her bliss.

One summer soon after joining the Supreme Court, Beverley McLachlin travelled to England for a legal conference for Canadians at Cambridge University.

Frank McArdle, who became involved with the legal conference in 1981, was a masculine, brainy type. He had once played hockey in his youth with the legendary Maurice (Rocket) Richard. (Mr. McArdle was on the junior Verdun Maple Leafs, and the Montreal Canadiens, the Rocket’s team, called him up for an exhibition game of past, present and possible future players.) And like Chief Justice McLachlin, Mr. McArdle, a father of three, had an adventurous spirit, having reinvented himself at the age of 47 by heading to law school, after years working in public relations and advertising. They married in 1992.

"There's always another page to turn, and you turn it," she said once, quoting her friend and colleague Claire L'Heureux-Dubé.

Justice L’Heureux-Dubé's own husband of two decades, Arthur, had died by suicide while she was still a young judge in Quebec.

In the face of loss, life demands resilience.

Beverley McLachlin – second row, third from right – poses with her classmates in the graduating class of Matthew Halton High School.

HANDOUT

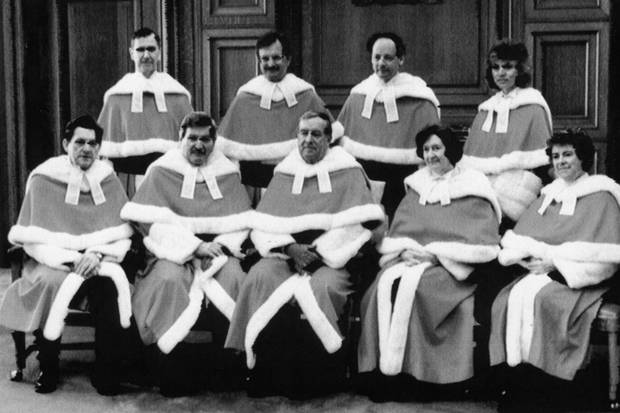

The justices of the Supreme Court, shown before Beverley McLachlin’s swearing-in on April 17, 1989. Top row from left: Peter Cory, John Sopinka, Charles Gonthier and justice McLachlin. Bottom row: Gerald La Forest, Antonio Lamer, chief justice George Brian Dickson, Bertha Wilson and Claire L’Heureux-Dubé.

FRED CHARTRAND/THE CANADIAN PRESS

The Supreme Court justices on Oct. 6, 2015. Top row: Suzanne Côté, Richard Wagner, Clément Gascon and Russell Brown. Bottom row: Michael Moldaver, Rosalie Abella, chief justice Beverley McLachlin, Thomas Cromwell and Andromache Karakatsanis.

CHRIS WATTIE/REUTERS

J

ustice McLachlin's early performance on the Supreme Court, beginning in 1989, was an astonishing tour de force.

The court was brimming with the titans who had taken on the earliest challenges of interpreting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms: Chief Justice Brian Dickson, a liberal lion. Bertha Wilson, the first woman on the Supreme Court, and a feminist icon. (In the 17 rulings in which both took part, the two agreed just once.) John Sopinka, a renowned authority on criminal law.

In this group, Beverley McLachlin was not shy to express herself.

Prominent among her powerful, controversial early written judgments was R. v. Keegstra. The 1990 case involved a rural Alberta teacher, James Keegstra, who was charged with promoting hatred, after teaching that all Jews are evil, that anyone evil must be Jewish, and that the Jews had "created the Holocaust to gain sympathy."

The case presented a pivotal moment for the young Charter. Did the Charter prevent government from limiting basic rights, including that of free expression, in the interest of protecting vulnerable minorities?

Justice McLachlin, writing in dissent, said it that did, at least in this case. "If the guarantee of free expression is to be meaningful," she wrote, "it must protect expression which challenges even the very basic conceptions about our society."

But Chief Justice Dickson's vision of the Charter, which carved out room for government to protect minorities, triumphed over hers, by a count of 4 to 3.

Next, she brought down the wrath of feminist critics. In R. v. Seaboyer, in 1991, the court struck down a federal rape-shield law that had protected victims from questions from defence lawyers about past sexual conduct.

Justice McLachlin wrote that the shield law was too sweeping because it did not allow for the possibility that previous sexual conduct would be relevant in some cases – though not for sexist purposes, such as establishing the complainant's credibility or likelihood of consenting. "It exacts as a price the real risk that an innocent person may be convicted," she wrote.

But just a year later, feminists applauded her. When Laura Norberg of B.C. sued her doctor, Morris Wynrib, for giving her narcotic painkillers in return for sexual favours, it was Justice McLachlin's written reasons, joined by Justice L'Heureux-Dube, that a quarter-century later seem to have stood the test of time.

She stressed that the doctor had violated his fiduciary duty – a special responsibility that people in positions of authority or trust have toward the vulnerable. (The men on the court also sided with Ms. Norberg, but largely for other reasons.)

"It's the humanity in every case that is so important to me, and it always has been," she told The Globe last month.

By 1993, just four years into her tenure on the court, Justice McLachlin was its most prolific author of judgments, with 36 – fully 10 more than the court's second-most prolific author, Justice Sopinka.

She was also its second-most frequent dissenter (after Justice L'Heureux-Dubé). One dissent stood out, in a case that riveted the country. Sue Rodriguez, 42, of B.C., had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and she wanted the right to seek assistance to die. Under federal law at the time, anyone who helped her to end her life could be punished with up to 14 years in jail. The court narrowly rejected Ms. Rodriguez's claim, by a count of 5 to 4.

"I thought it would be a simple matter for the Parliament of Canada to delete assisting a suicide as a crime," retired Supreme Court justice John Major, who was in the majority in that case, said in an interview for this story. "But they didn't have the courage."

Justice McLachlin, however, did not think Ms. Rodriguez should have to wait: Neither Parliament's failure to take up the issue, nor the lack of widespread acceptance of assisted suicide elsewhere in the world, mattered. "What value is there in life without the choice to do what one wants with one's life?" she asked in that ruling, perhaps channelling writer-philosopher Joseph Campbell again. "One's life includes one's death."

After a few short years on the court, she had made it clear where she was headed: She was a classical liberal – embracing an essentially conservative view that protected individual freedoms, whether of speech or of control over one's death, against encroachments from the state. And conversely, on the small-l liberal side, she displayed a willingness to view legal claims from the vantage point of the vulnerable.

Above all, she had planted her flag in the Charter's Section 7: the right to life, liberty and security of the person. The state could limit those rights, the Charter says, but only in accordance with "the principles of fundamental justice."

Beverley McLachlin's written judgments on this section presaged enormous social change. Even seemingly timeless laws such as those criminalizing prostitution or living off its avails – pimping – or injecting illegal drugs, in some circumstances, would soon feel the force of the legal arguments she had put in motion.

Beverley McLachlin came from recent immigrants who had left behind a world of upheaval and injustice. Her paternal grandparents were ethnic Germans, farmers, living in the Pomeranian region of Central Europe (which had at times been part of Germany, at other times of Poland). During the First World War, the German army took over the family home to house troops. After the war, she says of her grandparents, "At one point they had a Jewish family living in their basement to be protected against some sort of pogrom that was going on."

So they left in 1927, bringing their offspring, of whom they had 13, and money to invest in land and education. "The whole atmosphere was such that, although they were prosperous, they did not see much future for their children."

The future chief justice came to law through religion. "There was a strong tradition of debate and study," she recalls. "You were always reading the Scriptures and talking about them. My father was kind of a scholar of this. And so, I grew up with lots of philosophizing and debate. I think that had an impact on my mind as I grew up."

Fittingly, her hometown was founded to protect the rule of law. The North-West Mounted Police, forerunner of the RCMP, set up in Pincher Creek in 1878 to breed the horses they needed to patrol the West. The town was incorporated in 1906. There were no cities nearby: The closest town was Lethbridge, 100 kilometres to the east. Calgary, where Mr. Harper would one day serve as MP, was 220 km to the north.

Not every isolated community engenders positive values. But Pincher Creek is not just any community. It has produced at least four chief justices of Canadian courts. William Ives, a cowhand as a child – who did not attend elementary school till he was 21 – was chief justice of the Alberta Supreme Court from 1942-44. Val Milvain was chief justice of the Alberta Supreme Court Trial Division from 1971-79. Warren Winkler served as chief justice of the Ontario Court of Appeal from 2007-13.

Pincher Creek and the surrounding area seem to have had what today is called "social cohesion" – that intangible quality of healthy communities that helps children grow into happy, productive adults. "There was no demarcation between young people and old people," Mr. Winkler said in an interview. "I grew up with grownups. I was included in everything. You got used to talking to people who were your elders but they treated you as an equal."

Privation and uncertainty bred resiliency. "Everybody went to jobs that were risky," he says. "There were miners, lumber people, cattle ranchers, oil workers. You went to work and it was dangerous and you might not come home."

A half-century after their Alberta childhoods, he and Chief Justice McLachlin would see each other at meetings of the Canadian Judicial Council, a disciplinary body of judges. She was the chair, he the vice-chair. Within seconds, they would be sharing stories of Pincher Creek, Mr. Winkler recalls, while the other judges groaned and said, "Here they go again."

A Robert McInnis painting of chief justice McLachlin’s hometown, Pincher Creek, hangs in the office of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada.

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

As a new Supreme Court judge, Beverley McLachlin visited the office of her colleague Antonio Lamer. On the wall was a large painting of rolling farmland, by Robert McInnis.

"I think that's where I grew up," she said.

Mr. Lamer said he didn't know where it was set.

"I'd like to buy it," she said.

But she couldn't: It was leased from a gallery, and in any event, he wouldn't part with it. Soon after, Mr. Lamer became chief justice and moved the painting into his new office.

More than a decade after that, on Jan. 7, 2000, Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien named Justice McLachlin to the top job on the bench; she was the first woman to hold the position. The McInnis painting of Pincher Creek was now in her office.

Her hometown invited her back early in her tenure as chief justice. It was naming a street after her, Bev McLachlin Drive. At the celebrations, a tall, handsome Indigenous man approached her with a gift: pearl earrings he had crafted himself. "Your parents were the most wonderful people, and I will never forget them," he told her.

He described coming to the Gietz sawmill as a boy, with his parents and several siblings. It was Ernest Gietz's birthday, and Eleanora Gietz invited the large family in for cake. His piece had the dime she'd baked into it for luck. Ms. McLachlin remembered the visit, and asked why he found it so meaningful.

"It was the first time I ever went into a white person's home," he replied.

Decades later, on Beverley McLachlin's watch, Indigenous peoples would be guaranteed a place at the table when government or corporations sought to develop lands that had been set aside under treaties. And even if those peoples had not signed a treaty, the court ruled in 2014, their ancestral lands belonged to them. "The doctrine of terra nullius [that no one owned the land prior to European assertion of sovereignty] never applied in Canada," the chief justice herself wrote, in Tsilhqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, in which a unanimous court granted title to an Indigenous group over a large swath of the B.C. Interior.

In the eyes of many Indigenous people, it was the biggest of all victories, because it gave First Nations enormous leverage in negotiations over proposed development of Indigenous lands.

"What they're doing is they're strengthening the negotiation hand of aboriginal people, who didn't really have a hand at all," Jean Teillet, a Vancouver lawyer who is the great-grandniece of Louis Riel, said in an interview for this story. "It's a little bit of a revolution going on in this country, I think."

Jan. 12, 2000: Beverley McLachlin, newly sworn in as chief justice, is offered pens by Mel Cappe, left, president of the Privy Council; prime minister Jean Chrétien and the Governor-General’s aide-de-camp, Jocelyn Turgeon, far right, as Governor-General Adrienne Clarkson looks on.

TOM HANSON/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Nov. 30, 2004: U.S. president George W. Bush talks with chief justice McLachlin at an official dinner in Gatineau, Que.

LARRY DOWNING/REUTERS

Nov. 19, 2008: Chief justice McLachlin and the other justices wait for the reading of the Throne Speech in Parliament Hill’s Senate chamber.

FRED CHARTRAND/THE CANADIAN PRESS

The Charter of Rights represented a potentially massive change to Canada's political system. And led by Chief Justice Dickson, judges seized the moment: If the Constitution was supreme, he said, judges were its guardians.

Collisions between the Supreme Court and politicians began to build in intensity.

Early on, those on the left of the political spectrum were concerned that socially progressive legislation would come crashing down. But before long, it was conservatives who were worried. The federal criminal law on abortion fell. The Supreme Court forbade Canada from extraditing suspects abroad to face the death penalty. Gay marriage became a reality.

As elected legislators began taking a back seat to unelected justices, attacks on "activist judges" – from the Reform Party and its successors on the right – became commonplace. McGill University political scientist Christopher Manfredi shares the concern about the role of judges in the Charter era. "There are reasons," he told The Globe, "to ask whether courts have the capacity to make the kinds of policy decisions they're being asked to make."

Even within the court, Chief Justice McLachlin was at times seen as pushing the court's scrutiny of laws too far. In a 5-4 ruling in Sauve v. Canada, in 2002, she wrote the majority decision declaring it unconstitutional for the federal government – the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien, in that case – to have taken away the right to vote from federal prisoners. The dissenters, in a decision from Justice Charles Gonthier, all but accused her of plucking such a constitutional right from thin air.

To this day, Justice McLachlin sees it differently. "I don't think you necessarily lose your humanity or your rights just because you're in prison or committed a very serious offence," she told The Globe. "I understand for many people this is counterintuitive."

She was now the face of a court that would be increasingly called on to justify its role in defending the rights of marginalized groups. In the House of Commons in 2003, Opposition leader Stephen Harper accused the Supreme Court of having illegally rewritten the Charter eight years earlier – in the case of Egan v. Canada – to include sexual orientation as a prohibited ground of discrimination in the equality clause, Section 15. (The framers deliberately left it off the list of protected groups; but the court had long since decided that the list was open-ended.) "I would point out," Mr. Harper said, "that an amendment to the Constitution by the courts is not a power of the courts under our Constitution." He had brought the emotional U.S. debate on "originalism" to Canada.

Still, sometimes Mr. Harper and Chief Justice McLachlin agreed on constitutional issues. Before he was elected prime minister, Mr. Harper was instrumental in bringing a case all the way to the Supreme Court on the right of citizens to advertise before elections. A Liberal government had passed a law strictly limiting such third-party advertising. Representing a conservative group, the National Citizens Coalition, Mr. Harper argued that this was an unjustifiable limit on freedom of speech.

He lost, 6 to 3 – but Chief Justice McLachlin was on his side. "This denial of effective communication to citizens violates free expression where it warrants the greatest protection – the sphere of political discourse," she co-wrote in dissent, with Justice Major, in Harper v. Canada in 2004.

But the gulf between them remained.

Under her predecessor, Antonio Lamer, the court had sometimes broken into multiple factions, obscuring the meaning of decisions. But as Chief Justice McLachlin tangled with the fledgling Conservative government, she became a unifying force on the court.

"If you couldn't get five judges on the same decision, you then had a lack of clarity as to what the court was deciding," Ian Binnie, a judge on the court from 1998 to 2011, said in an interview for this story. "So, without pushing people to a particular outcome, she would urge all of us to rethink our positions to at least have five of the nine judges saying the same thing."

Off the bench, too, she tried to hold the court together. During one fractious period within the court, she invited her colleagues to prepare a meal at her home, under the direction of the Supreme Court chef, Mr. Binnie recalled: "So we were all instructed to clean fish and peel vegetables, which brought people together on a personal level at a time when there were some professional differences that needed to be healed."

Mr. Winkler said he gained an insight into her subtle leadership style by observing her at Canadian Judicial Council meetings. "You get to the end of a meeting and you say, 'How did we get to this position?' And then you look back: She got you there. But she didn't come in and say, 'Here's what we're going to do.' You never thought she dictated or compelled the conclusion. It's like magic to see."

Thus, when three major cases arrived at the court on the right to life, liberty and security of the person – Chief Justice McLachlin's sweet spot – the court was ready to speak clearly and with one voice.

The first of those cases, in 2011, involved the Harper government's stated "war on drugs."

Since 2003, cocaine and heroin addicts had been injecting drugs under nursing supervision at Vancouver's Insite clinic. Now, however, the federal government wanted to close the clinic, arguing that it promoted drug use and addiction.

The judges balked. Chief Justice McLachlin, writing for a unanimous court, said that the federal approach was not in accordance with "the principles of fundamental justice," because it would increase the risk of death or disease to the vulnerable, an effect grossly disproportionate to any benefits such an approach might have. The clinic stayed open.

The second case, in 2013, involved prostitution laws (street soliciting, running a bawdy house, living off the avails) predating the Conservative government. Again, all nine judges stood together. Again, Chief Justice McLachlin penned the ruling. As in the Insite case, she wrote that the prostitution laws put the lives of vulnerable Canadians, in this case sex-trade workers, at risk. The court struck down the prostitution laws, thus allowing sex-trade workers to ply their trade legally, in dwellings or on the street. (A subsequent Conservative law criminalized those who purchase sex.)

The ruling had an added consequence, far beyond the case: It gave lower-court judges the right to overturn precedents in certain circumstances, even those set by the Supreme Court. Until then, only the Supreme Court could topple its previous rulings. But now, if a trial judge found new "social facts" – such as a new understanding of how certain laws add to the dangers of the sex trade – that judge could revisit what seemed to have been a settled constitutional matter. And higher courts would have to show deference to the trial judge's findings on how times had changed. Precedent is "not a straitjacket that condemns the law to stasis," Chief Justice McLachlin wrote.

This was the "living tree" on steroids, exactly what Mr. Harper opposed. But he had not been able to find the Canadian equivalent of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, a believer in a "frozen Constitution."

The third case, Carter v. Canada, in 2015, was a reprise of the 1993 assisted-dying case. And the prostitution ruling sealed it. A lower-court judge in Carter v. Canada had found as a fact that, in countries that allowed assisted dying, the vulnerable were protected. Under Chief Justice McLachlin's judgment in the prostitution case, the Supreme Court judges had little choice but to defer to this critical finding.

The government's central rationale for criminalizing assisted dying (protecting those vulnerable to being pressured to die) was thus shattered. The 9-to-0 Supreme Court ruling lifting the ban on assisted dying was authored not by the Chief Justice but by "the Court," giving it extra oomph.

Chief Justice McLachlin's vision was triumphant: Section 7 (the right to life, liberty and security of the person) now placed strict limits on what might be described as legislating morality. Individual rights would prevail over community standards. Bradley Miller, a conservative law professor later appointed to the Ontario Court of Appeal by the Harper government, said that governments had been deprived of the right to make their arguments on behalf of larger societal interests. "Justice and justification are to be considered from one side only," he wrote on a British constitutional blog before becoming a judge.

Even if only one person was wronged, a law could fall.

Federal Court of Appeal Justice Marc Nadon was an outspoken small-c conservative (though not a Scalia-like originalist). He was also semi-retired.

When Mr. Harper appointed him to the Supreme Court in 2013 – to replace Morris Fish of Quebec – a legal challenge began over whether he had the legal qualifications. In 2014, the court ruled that he did not. It was the court's first rejection of an appointee in its history.

That was just one case in a losing streak for the Harper government. In five major cases, the government found just a single vote – once – on the Supreme Court. Three involved tough-on-crime laws central to the government's political agenda. In the last of the five, the court turned thumbs down on the government's wish to make the Senate an elected body.

That Senate ruling seemed to be the last straw for Mr. Harper. Soon after, the Prime Minister's Office put out a news release saying that Chief Justice McLachlin had sought to interfere in a case before the court – the Nadon case. It said she had inappropriately called Justice Minister Peter MacKay, and had tried to call Mr. Harper, who would not take the call. "Neither the Prime Minister nor the Minister of Justice would ever call a sitting judge on a matter that is or may be before their court," the news release stated.

That same day, the Chief Justice had been giving a speech at the University of Moncton on women and the law. She did not learn of the PMO's statement till four the next morning, as she hurried to catch a plane to return to Ottawa. "I obviously was shocked and dismayed," she recalled in the interview in her office. "I thought, 'This is not right. This is not true.'"

Back in Ottawa, she met with her executive legal officer, Owen Rees, and decided to speak out.

"I never felt fear. I didn't even feel anxiety, as I recall. I just felt this was wrong. I did not want it to tarnish the office of chief justice or the court. I had devoted my whole life, or a good part of it, to doing whatever I could to make the court a wonderful and hopefully respected institution. My concern was that somehow this might tarnish the image of the court."

She says she told Mr. Rees, "'We're going to put out a statement and deny any wrongdoing' – which there was none – 'and just set out the facts.' That's what we did. We set out the dateline of when that call was – which, by the way, was several months, I believe, before the candidate in question's name ever came up. The call was a purely administrative one of the nature that chief justices make to the justice minister from time to time."

(As The Globe later reported, the PMO had created a list of six candidates for the Supreme Court, of which four, including Justice Nadon, were from the Federal Court's trial and appeal divisions. No Federal Court judge had ever filled one of the three places reserved for Quebec on the Supreme Court, because the law did not explicitly allow it. When Chief Justice McLachlin was shown the list, she contacted Minister MacKay to warn him of the legal roadblock. But the confidentiality of the process prevented her from publicly revealing these details.)

In his recent interview with The Globe, Mr. Mulroney said there was nothing unusual in a chief justice contacting the justice minister over an administrative issue. "Look, when I was prime minister, I would frequently sit down with the chief justice and hear his views on the operation of the federal courts generally in Canada. I would ask, for example, in respect of appointments, what he might think of A, B or C. This was Tony Lamer and Brian Dickson. I would have the chief justice for dinner at 24 Sussex when there were special dinners going on."

He added that Mr. Harper, in his view, had been deeply in the wrong. "The Supreme Court is the backbone of Canadian democracy," he said. "That is diminished when a person in authority like the prime minister attacks, publicly, the chief justice of the Supreme Court."

Mr. Harper did not respond to The Globe's attempt to contact him for this story.

In the backcountry near Pincher Creek, Dick Hardy, a modern-day cowboy who bought the planks for his first corral from the Gietz sawmill, was not impressed by the prime minister's actions.

"I was a Harper fan," the 75-year-old, who went to high school with the chief justice, said in an interview. "I had a great respect for his management, fiscally, of this country. But he was out of school on that one.

"But how gracefully did she handle that."

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In her years on the court, Beverley McLachlin did not wear her heart on her sleeve. Cool, methodical logic was her domain.

"There's a certain effacement of who she is, even in her judicial writing," says David Sandomierski, one of her former law clerks. "She really inhabits the cloak of her office, which entails a concealing of her own person. I view her as an avatar for the court."

The closest she came to a passionate display, perhaps, was in a speech in 2015, in which she said that Canada – led by its first prime minister, John A. Macdonald – had committed cultural genocide against Indigenous peoples in its use of residential schools for assimilation. She called this the "most glaring blemish on the Canadian historic record." But even that, according to her, was a simple statement of fact that she did not think was controversial.

Wrote Joseph Campbell, explaining what it meant to follow one's bliss: "The heroic life is living the individual adventure."

Beverley McLachlin's personal adventure has been unstoppable. She emerged from her pre-electricity, horse-riding childhood to become a modernizing force in Canada, spending 17 years as chief justice – and 28 years in total on the Supreme Court – in the 35 years since the Charter of Rights took effect. And she more than pulled her weight: She wrote or co-wrote 172 of the court's roughly 1,000 reserved decisions while chief justice, about one in six – including many of the most important decisions, according to political science professor Peter McCormick of the University of Lethbridge.

Her legacy, covering virtually every area of the law – from strong protections of due process for suspected terrorists and criminals, to a new legal footing for Indigenous peoples, to the resounding independence of Canada's highest court, to the vibrant growth of the "living tree" of constitutional rights – is now part of the country's foundations.

As for what comes next, more adventure seems likely. She has written a mystery novel, Full Disclosure, to be published this spring. And she'll have a little more time to follow other pursuits as well.

"We both agree there's more to life than just sitting around," says Mr. McArdle, who is now 89. "I'm sure we'll find something interesting to us."

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article included incorrect information about the number of children Mr. McArdle has. This version has been corrected.

THE SUPREME COURT AFTER McLACHLIN: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL