Illustration by Bryan Gee

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article included an incorrect month for the G7 meeting. This version has been corrected.

Chris Turner’s books include The Geography of Hope: A Tour of the World We Need, The Leap: How to Survive and Thrive in the Sustainable Economy, and The Patch: The People, Pipelines, and Politics of the Oil Sands, which won this year’s National Business Book Award.

Back in September, environment and energy ministers from across the G7 met in Halifax to discuss cleaner oceans and greener energy. As per the norm in such circles, the proceedings were stiff, technical and wonky as all hell, and so the meetings barely cracked the week’s news cycles. There was some coverage of the Canadian government’s intentions to join in international efforts to reduce plastic waste and phase out single-use plastic in its own operations. The bigger stories, though, were Environment Minister Catherine McKenna’s response to David Suzuki’s demand that she resign and Natural Resources Minister Amarjeet Sohi’s announcement about the government’s next steps to get the Trans Mountain Pipeline built. “Sohi made the announcement in Halifax, where he is hosting G7 energy ministers,” a Canadian Press story noted in passing.

Natural Resources Minister Amarjeet Sohi addresses a session at the G7 environment, oceans and energy ministers' meeting in Halifax.Andrew Vaughan/The Canadian Press

The year’s political news has been completely dominated by furor over Trans Mountain, of course, and the dismissal of the pipeline’s approval by the Federal Court of Appeal was greeted by Indigenous activists and environmentalists as a ringing victory. The political conflict over the pipeline has churned up such a political morass that it’s hard to find much in the way of near-term gain for climate change action in the midst of it all. The more likely outcome is that the fragile consensus responsible for Canada’s modest efforts to date will be sucked down into that mire for years to come. And so the G7 meeting was a reminder that despite all the calamity, Canada does still have good climate policy in place. Much of it is gathered under the banner of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, the coordinated federal-provincial plan stitched together in the spring of 2016 and in constant danger of being torn to shreds ever since. Wonky conferences, like the one in Halifax, which tend to transpire with little notice and no celebration, are a big part of the daily grinding work of good climate policy.

It was perhaps to be expected, then, that the Framework saw mention in precious few of the breathless news stories covering this week’s release of the latest report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The Framework’s incremental initiatives surely seem all out of proportion to the IPCC’s stark warning that human civilization has until 2040 at the latest to slash greenhouse gas emissions worldwide if we intend to avoid major climate catastrophe. What did a little good climate policy matter in the face of that?

What I mean by good climate policy, to be clear, is climate policy that has actually been passed, has become the law of the land, and has then been sent off to do its quiet work of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That work tends to be far less noticeable than the screaming headlines above news of imminent disaster or even the final sum on a household energy bill. British Columbia’s carbon tax, for example, is good climate policy. Since the tax was introduced in 2008, gasoline use is down by more than 10 per cent per capita in B.C. and emissions have shrunk by five per cent, even as the province’s economy has grown steadily. But it remains so inconspicuous that even 10 years after it was enacted, the majority of British Columbians still can’t say for sure whether there’s a price on carbon dioxide emissions in their province. That’s often the way with good climate policy – when it’s working well, you hardly know it’s there.

Good climate policy pleases no crowds. There are no raucous rallies or victory marches in its name. Good climate policy simply doesn’t cause too much fuss, satisfying the majority of Canadians who claim to want something done about climate change – something real, measurable, effective – but not so much that it really stings. Good climate policy is like fire insurance or storm drainage – no one wants to think about it, but they want it there to do the job when it’s needed. But climate policy is needed now at a scale and scope far beyond any given fire or flood – ultimately, we need it to intervene in every transaction involving fossil fuels everywhere on earth – and so it is getting harder for good climate policy to stay quietly out of sight. And because no one likes the look of good climate policy in the light of day – because it seems pitifully weak on its face and embarrassing in its concessions and awkward compromises – it is hard to maintain and defend. Mercilessly hard.

Why is good climate policy so hard to love? The answer, like climate change itself, is multivalent and excruciatingly complex, and it has a lot to do with the scale and time frame of the problem and its solutions. No one’s climate policies can move fast enough to yield tangible everyday benefits before the next election. There will be no immediate reward for doing the job well, and rarely does an instant crisis emerge from doing it badly. And in any case, good climate policy satisfies no one completely and makes everyone at least a little uncomfortable. In the foreshortened terms of a bellowed Question Period exchange, the carbon price – any carbon price – is always so high that it will ruin the economy and so low that it will do nothing. Good climate policy is never an easy political win, and even the hard wins seem like losses from many angles. It’s a sinkhole for political capital, a kryptonite mine against the superheroic political will required to address climate change’s catastrophic scope.

Still, good climate policy is the best we can manage right now – in Canada or anywhere else – and we’re in grave danger of squandering what we have in exchange for nothing at all. So it’s worth trying to understand how it fails to win much adulation.

June 12, 2006: The third of four smokestacks, known as the Four Sisters, crumbles during a demolition at a defunct coal-fired power plant in Mississauga. Ontario managed to eliminate coal-burning power from its electricity grid within a decade.Reuters

Canada has had some good climate policy over the years, though not too much, and it has even more now, though nowhere near enough. But what Canada mostly has, 30 years after Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government convened the world’s first major climate conference in Toronto and three years after Justin Trudeau’s Liberals came to power hellbent on launching the nation’s first comprehensive climate policy package, is an acrimonious stalemate. Carbon pricing has drawn the ire of conservatives nationwide, while trading off an oil sands pipeline approval for conservative buy-in on Mr. Trudeau’s climate package has environmentalist leftists marching in the streets. Never mind that the majority of Canadians – 76 per cent, according to an October 2016 survey by Abacus Data – claim to reside somewhere in between, open to the idea of a new pipeline project alongside more aggressive action on climate change. They say they want good climate policy, in other words, but they aren’t howling for it. And so they are barely heard. This is how good climate policy fails.

Consider Ontario’s coal phase out – a climate policy so good it verged on great. It did exactly as promised, entirely eliminating coal-burning power plants from the province’s electricity grid in barely a decade. The phase out reduced smog, prevented thousands of premature deaths and created what the Ontario Power Authority justly touts as “the single largest greenhouse gas reduction measure in North America.” It is too often remembered now, though, as a prelude to the nasty battle over the province’s Green Energy Act, whose clumsy implementation turned neighbour against neighbour in wind-farm development battles across rural Ontario, sowed misinformation about the causes of skyrocketing energy bills, and helped feed the throw-the-bums-out anger that led to the carbon-price-killing reign of Premier Doug Ford.

June 28, 2018: Federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna speaks at a news conference after a meeting with her provincial and territorial partners in Ottawa, soon after the Ontario government said it would scrap its cap-and-trade program.PATRICK DOYLE/The Canadian Press

And then there’s the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, Canada’s first real national climate plan, which is the essence of good climate policy. One way to tell it’s such good climate policy is because unless you’re a policy wonk, you might have never heard the full name of it until I mentioned it earlier. This, despite the Framework being easily the most ambitious climate policy package the country has ever seen, is coordinating climate change action between the federal government and every province and territory other than Saskatchewan. The Framework expands Ontario’s coal phaseout nationwide by 2030 and commits all but the Saskatchewanian among us to dozens more changes in how we make and use energy, all to accelerate our pursuit of the greenhouse gas reductions we committed to at the Paris climate summit in 2015. (Fully one-third of those reductions can be achieved if governments nationwide implement only the efficiency measures prescribed by the Framework.) It’s accompanied by a national carbon price, which might also be deemed good climate policy if you weren’t so much more familiar with it – in a screaming-headlines and Ford-Nation-rallies kind of way – than you likely are with every other detail of the Framework.

We’ve all heard plenty about the carbon tax, of course. Or, rather, the job-killing carbon tax. Or Mr. Trudeau’s reckless carbon tax. Or else the insufficient carbon tax, the window-dressing carbon tax, the carbon tax negated by oil sands expansion. Such notoriety turns out to be deadly for good climate policy because a new tax on an environmental problem many people only vaguely understand, levied in order to solve that problem at some indeterminate point in the future, but only after the vast majority of the world’s emissions not currently subject to a carbon price are drawn into the fold, turns out not to be a formula for a political slam dunk. Even a report released just a few weeks ago – produced by a think tank headed by a former Conservative policy adviser, no less – showing how most Canadian households will receive more money back in rebates than they will pay in carbon taxes has done nothing to change the tenor of the debate. This was underscored last week when Mr. Ford joined United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney in Calgary to rally against carbon taxes – mere days before economist William Nordhaus of Yale University was named a co-recipient of this year’s Nobel Prize in economics for his work establishing that putting a carbon price was the most effective way to fight climate change. In front of a boisterous crowd of more than 1,000, Ford called Mr. Nordhaus' Nobel-winning idea “the worst tax ever.” The rally was a reminder that even as the IPCC was informing the world that nowhere near enough was being done about climate change, Canada already had sufficient climate policy in place to inspire angry rallies against it.

The extraordinary machinations the federal government has undertaken of late to begin work on a pipeline to transport Alberta’s bitumen from Edmonton to the Pacific coast represents just the most prominent reason why its good climate policies are finding so few champions. There are myriad other reasons, from the squabbling over jurisdiction endemic to the Canadian federation to the bounteous political hay to be made these days on both the right and left flanks of Mr. Trudeau’s Liberals. Put another way, the fragile coalition needed to keep the Framework in place has, since it was formed, subbed in Mr. Ford and B.C. Premier John Horgan as the custodians of two of its three biggest partners. You try keeping smiles on everyone’s faces at the grip-and-grin after that.

Oct. 5, 2018: Ontario Premier Doug Ford, left, and Alberta's United Conservative Party Leader Jason Kenney greet supporters on stage an anti-carbon tax rally in Calgary.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

If good climate policy is so likely to lead to such a political mess, what of the other options? These can be categorized broadly as great climate policy and no climate policy. Let’s start with the latter, which is the current position of most Canadian conservative parties. To be fair, conservative politicians have finally been persuaded to pay some grudging bare minimum of lip service to the scientific reality of the situation. “Virtually everybody accepts that there is such a thing as a man-made contribution to climate change and we have to be prudent in reducing greenhouse gases” – this is Jason Kenney’s rousing rallying cry on the topic.

In practical terms, however, the Canadian right has not presented any comprehensive climate policy package since the federal Conservatives tabled and then abandoned their “Turning the Corner” plan in 2007. The rationalizations for this have ranged from a self-serving sort of realism (think of Stephen Harper explaining that “no country is going to take actions that are going to deliberately destroy jobs and growth”) to blithe hand-waving at the coal-spewing power plants of China and dismissive reference to the statistical tables attesting to the fact that Canada remains a small country, population-wise, when you compare it to the whole world. We can’t fix the whole problem all by ourselves, so goes the line of reasoning, and many others aren’t even trying. So why should we?

Under Andrew Scheer, more than a decade after Mr. Harper’s government failed to turn any corners, the new federal Conservative climate policy plan remains top secret. It remains hard to imagine any other policy issue of such consequence on which a viable political party can simply take no substantive position at all. So treacherous is the swamp of climate politics that a shrug from the shore can seem like the least damaging stance.

Supporters wave signs during Mr. Kenney and Mr. Ford's anti-carbon tax rally in Calgary.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

The stronger argument against good climate policy comes from advocates of great climate policy. Great climate policy posits that good climate policy and all its meek, compromised incremental changes are themselves a big part of the problem. If only a courageous government was willing to take much greater strides, or even an enormous leap – the kind perhaps charted in a multi-point manifesto – well, then we would see the kind of rapid transformation needed not only to forestall climate change, but to build a better society in every respect. We would not only keep all the oil in the ground and slash emissions, we would liberate Canadians through renewable power and decentralized grids. There would be a solar panel on every roof, an electric car in every garage, a bike lane or LRT track on every street. This was the kind of response that this week’s alarm-ringing IPCC report was calling for, ideally implemented as of yesterday.

It’s a wholly admirable vision. I’ve spent a great deal of the past 10 years sketching in its contours (and, full disclosure, I was a writer on the Generation Energy report on this theme released by Natural Resources Canada earlier this year). Who wouldn’t want to strive for it? But on the question of how to reach it, great climate policy encounters one formidable hurdle: It doesn’t exist. Or rather, it doesn’t yet exist. It has never been enacted, nor is it built into the platform of any political party with a legitimate near-term shot at forming a government in any major industrial nation. This is in part because great climate policy tends to treat politics as an afterthought – which, when you think about it, is an odd way to advocate for a policy package.

What of the many special cases I’m skipping past – the true leaders, some of which I’ve reported on myself in admiring detail? Consider Germany, the first major industrial economy to commit in a substantial way to eliminating fossil fuels from its electricity grid – and then set back that project by a generation when Angela Merkel’s government shut down the country’s nuclear plants instead of its coal-fired ones in order to save its own political hide. What about Norway? Aren’t they buying electric cars faster than they can be rolled off production lines? Most definitely – because those EVs are exempt from a domestic luxury tax that doubles the price of vehicles that burn gasoline. Try selling that to the autoworkers of Oshawa and Windsor (not to mention the commuters of Surrey and Laval). And haven’t you heard that the great state of California just committed to 100 per cent clean power by 2045? Certainly it did – with an interim goal of 60 per cent by 2030. It’s an impressive, pacesetting model for much of the United States. But if you’re wondering about the corresponding Canadian figure, 81 percent of our electricity nationwide comes from emissions-free sources today. Admittedly, this is down to abundant hydroelectricity more than good climate policy. Still, the point stands: there’s not much in the way of great climate policy even in the vanguard.

July 21, 2018: Electric vans charge up at a warehouse of the postal and logistics service Deutsche Post near Frankfurt am Main. Germany was one of the first big industrial economies to commit to eliminating carbon from its power grid, but Chancellor Angela Merkel changed tack, shutting down nuclear plants instead.YANN SCHREIBER/Getty Images

In place of the molasses-slow muddle of everyday politics, great climate policy calls on the transformative power of science and urgency. As the IPCC reminded us again this week, climate science has made itself abundantly clear about the size and speed at which greenhouse gas emissions must be cut in order to avert climate disaster. Climate policies, then, must deliver those cuts. ASAP. This, as great climate policy advocates repeatedly note, is what the science tells us must be done. But as long as elected politicians and not scientists remain in charge of writing the actual legislation, and as long as those same politicians continue to need the support of voters in order to keep doing that work, the science telling us what to do will likely continue to prove as ineffective at making great climate policy a reality as it has to date.

In the face of such intransigence, great climate policy’s boosters invoke the mystic power of urgency. There is no time to wait, they say, for the usual machinations of ineffectual government and grinding bureaucracy. This is an emergency. Normal rules don’t apply. Over the years – decades, now – the necessary response to climate change has been compared to the Apollo project that put a man on the moon, the New Deal that helped end the Great Depression, and, most often, to the command-and-control expediencies of the Second World War. Soon there will come a catalytic moment – most likely one of the growing number of extreme-weather disasters that have already become a hallmark of life in the age of climate change and an obsession among the many advocates of great climate policy I follow on social media – and the blinkers will be lifted from all heretofore unconvinced eyes, the wisdom and necessity of rapid, radical action made manifest and unstoppable.

Oct. 11, 2018: Homes lie destroyed in Mexico Beach, Fla., where Hurricane Michael made landfall days earlier. Extreme weather events are becoming more commonplace in the era of climate change.Pool/Getty Images

In the aftermath of such a moment of mass clarity, the revolution will emerge everywhere. It will be guided by a rapid wholesale reinvention of the entire apparatus of modern politics, which will respond to the catalytic catastrophe not with chaos or authoritarian self-preservation, but only with flawlessly orchestrated collective action. This tipping point has been prophesied in green circles for nearly as long as climate change has been a phenomenon on the global political radar, and it appears not much closer at hand today. (The authoritarian self-preservation thing, however, appears to be having its moment.) In the meantime, however, among the mass of people not yet mobilized to fight climate change on the beaches and in the fields and in the streets, that sense of paramount urgency stubbornly refuses to arrive. Something that remains “urgent” for 20 years, after all, is fundamentally not urgent to most people’s way of thinking. A wildfire on the edge of town is urgent. A round of layoffs by the big local employer is urgent. A crisis that changes essentially nothing about your daily life for years on end is not urgent. It has proven far easier to inspire a sense of urgency around the use of plastic straws.

There is now even a kind of nostalgia for the fleeting urgency of times past. Nathaniel Rich’s epic rundown of the progress and sudden halt of climate policy in the halls of American government in the 1980s, which sprawled across an entire recent issue of the New York Times Magazine, is a case in point. Mr. Rich reports in vivid and convincing detail on the sense of urgency that briefly pervaded environmental policy circles in those years, driven by the first strident alarm calls from a range of climate scientists and enlightened public officials.

Mr. Rich’s piece is crackerjack historical reporting. But his apparent conclusion, echoed in the white-text headline that is the only splash of light on a black cover – “Thirty years ago, we could have saved the planet” – does not follow at all from the evidence he lays out. That royal “we” elides a broad range of democratic institutions and economic forces that fundamentally did not want rapid change then and still aren’t sure about it now. And this is not just limited to the handful of fossil fuel companies who have willfully obfuscated the climate change debate. Long-established political systems – and political parties – don’t readily embrace rapid change. They aren’t built for it, don’t understand it, and can’t manage it very well. Mainstream banks and pension funds don’t tend toward rapid change. Industry advocacy groups, chambers of commerce, neighbourhood associations – none of these are designed to drive rapid change. Put another way, try convincing the community association in an established low-rise neighbourhood anywhere in North America that they should readily embrace a 10-storey condo development because it will bring welcome and necessary density, enabling greater walkability, affordable transit and even making car-free living a possibility – all crucial urban pieces of any serious long-term response to the climate crisis. Gauge the reaction, and then tell us again how the public in general was ready for a wholesale shift of sufficient scale to combat climate change in 1989 (or 1997 or 2009), but for the media machinations and backroom shenanigans of the oil companies.

Urgency, then, is an expression of solidarity more than a coherent plan. Consider the climate policy efforts to date from a political party that often invokes the urgency of what the science tells us – the NDP. Starting around 2008 with federal leader Jack Layton, who had been talking a great game about climate change before he took the helm of the party and then threw carbon pricing and everything else in Stephane Dion’s Green Shift policy package under a campaign bus to lay the groundwork for finishing second in the 2011 election, the NDP response to climate change has mainly been a kind of strident incoherence. Even as Mr. Horgan thundered against the menace of the Trans Mountain Pipeline this spring, for example, he was also urging the federal government to take action to reduce gasoline prices. (His calls were echoed by Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwath on the campaign trail). The B.C. NDP might be steadfast in their opposition to pipelines, but this does not spill over into any kind of policy-oriented hostility toward the consumption of their contents. Mr. Horgan’s government even cancelled tolls on the bridges crowded beyond capacity by suburban Vancouver motorists as an additional show of support for the continued reign of the internal combustion engine.

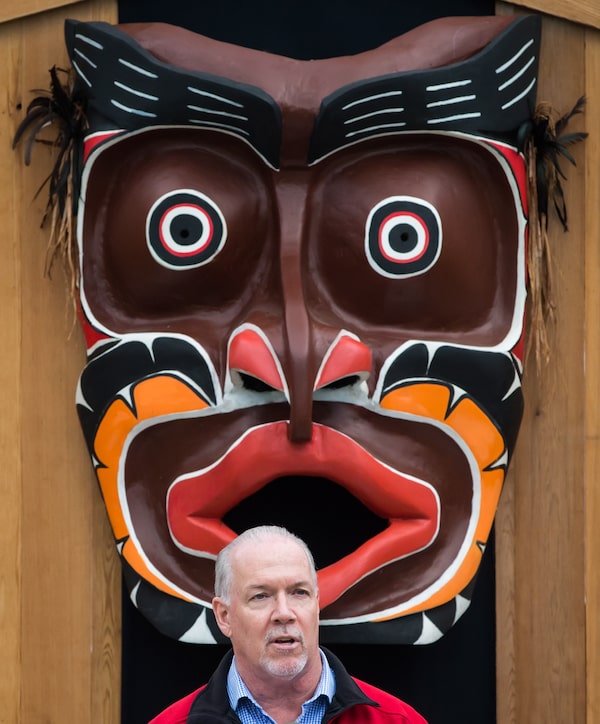

B.C. Premier John Horgan, shown at an event in Surrey in September, has inveighed against the Trans Mountain pipeline, but has shied from other measures that would curb British Columbians' fossil-fuel consumption.DARRYL DYCK/The Canadian Press

Wouldn’t urgency – real urgency – necessitate working with whatever government currently holds the reins of power, at least insofar as that government is willing to act? Wouldn’t a slow start be better than standing still? Wouldn’t a binding price on carbon pollution, the end of coal-fired power, and a deepening commitment to renewable power and energy efficiency and mass transit from every government in the land – wouldn’t all of this right now be worth quite a lot in the way of odd bedfellows and uncomfortable compromises?

This, in any case, was the strategic thinking behind the Pan-Canadian Framework, which presented Canadians with carbon pricing and the rest, all waltzing awkwardly with a pipeline approval. There was Alberta premier Rachel Notley at her climate plan’s launch, photo-opping in a single frame with the executive directors of environmental groups, the chiefs of First Nations, and the CEOs of oil companies, all of them united uncomfortably in support of the whole good climate policy package. And what a freakish once-in-a-generation moment it was: Canada’s largest oil-producing province, without which any united action would be meaningless, stood in solidarity for the first time possibly ever with both the prime minister and every premier not named Brad Wall on the long-term direction of oil and gas development. This was, if you will, the forging of the Trudeau-Notley consensus – a brief interlude of relative agreement during which just enough momentum might be generated behind good climate policy to make it a fixed feature on the Canadian political landscape. Just maybe enough gears could be sent spinning slowly in the same direction to get the machine moving toward the much more vigorous work that would eventually be necessary to tackle the climate crisis more thoroughly. The trade-off was far from cheap – a pipeline delivering 600,000 additional barrels of Alberta bitumen to the Port of Vancouver – but it was, for the architects of the consensus, the only way to put the whole messy apparatus in motion.

Sept. 5, 2018: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Alberta Premier Rachel Notley meet in Edmonton. Both leaders support the building of the Trans Mountain pipeline from Alberta to the B.C. coast.JASON FRANSON/The Canadian Press

When the Federal Court of Appeals quashed the federal government’s approval of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, the First Nations and environmental groups that had fought to stop the project greeted the decision with victorious celebration. I certainly don’t begrudge them their exultation – the pipeline came freighted with threats to coastal ecosystems and Indigenous land rights that they simply deemed too much to pay. But I don’t see much to celebrate on the climate policy front. The fragile Trudeau-Notley consensus is in shards. Whatever becomes of the pipeline itself, I’d place the smart money on another decade or more lost to its political fallout. The ongoing fight will be mean, and it will feed reactionary politics on all sides, and 10 years from now we might well be no closer to shrinking Canada’s carbon footprint for good than we were during that rare interlude of 2016.

It would please me to be wrong. If there is a viable political path from here back to deeper, faster action – to more good climate policy and beyond, all the way to the uncharted territory of the great – I’d love to see it.

The Trudeau-Notley consensus is – was – an ugly deal. It ran roughshod over the land rights of a number of First Nations, amplified the risk of ecological disaster in the Salish Sea, and provided a sort of buffer to fossil fuel industries still reluctant to face twilight head on. But it was the best shot we’ve ever had at turning the corner decisively on a crisis that counts in decades and centuries. Maybe – just maybe – it could have built a consensus sturdy enough to survive a couple more election cycles and become, like health care or multiculturalism, a permanent fixture. Canada might even have emerged as a sort of model. Now we are in imminent danger of becoming just one more country with no plan at all, going nowhere fast.

Feb. 8, 2018: Protesters opposed to the expansion of the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline block an entrance to the Westridge Marine Terminal in Burnaby, B.C.DARRYL DYCK