Photo illustration by The Globe and Mail

Chris Alexander served in Afghanistan from 2003 to 2009 – first as Canada’s ambassador, then as deputy head of the UN mission. He was minister of citizenship and immigration in Stephen Harper’s Conservative government. Before 2003, he also served for six years in the Canadian embassy in Moscow, including as deputy head of mission.

For roughly as long as there have been democratic elections, there has been the threat and practice of foreign interference. Certainly, new developments have made the challenge even more daunting: Social-media platforms, buttressed by TV propaganda and old-fashioned corruption, have given today’s malefactors impunity with global reach. But there has always been interest in luring democracies, powered by the will of the people, to bend to the will of those who trample on democratic rights in their own states.

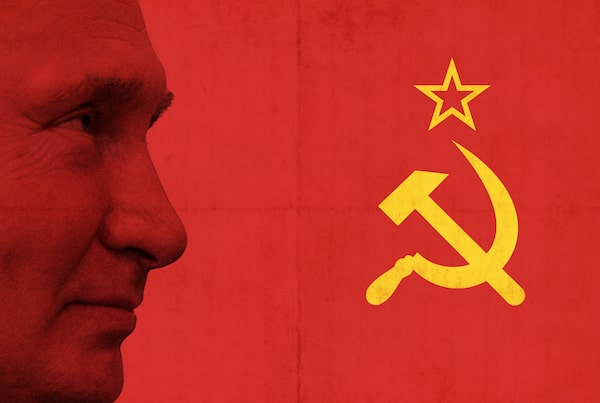

In our era, no country has embraced this kind of trespass – warfare, really – with greater abandon than Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

His goal is simple: discredit democracy. By making elections seem like pointless contests of extremes in which moderate views are trampled, he seeks to bolster dictatorship as an alternative. By taking issues that have historically made democracies strong and turning them against those very societies, the Kremlin seeks to promote confusion and chaos.

His inspiration is similarly easy to understand: Mr. Putin’s efforts are fuelled, ultimately, by his halcyon view of the Soviet Union.

In his lifetime, he bore witness to its rise, so he sees its dissolution as a tragedy; reversing this catastrophe has required dramatic methods. It has meant ending freedom of speech. It has meant that the Kremlin now redirects, often by the crudest possible means, Russia’s decades-old Orwellian machinery of internal disinformation toward international audiences. It has meant invading Georgia in 2008 to frustrate that country’s bid to join the more prosperous Euro-Atlantic community of countries.

Perhaps above all else, it has meant needing a compliant subordinate in Kiev, to prevent Ukraine from going down the same path. No event did more to upend Mr. Putin’s strategy of Soviet revivalism than the launch of the Euromaidan movement in November, 2013, which triggered an unprecedented five-year period of reform and European integration for Ukraine. The fall of its quisling regime under Viktor Yanukovych was such a shock to the top-down system of Mr. Putin and his coterie that grabbing Crimea and invading Ukraine’s Donbass region seemed reasonable by comparison.

Yet, Mr. Putin’s regressive behaviour is about more than poisoning democratic debate or taking revenge for Ukraine’s European turn. It speaks to a dangerous reversion to the mindset of a man who only shared this Earth with Mr. Putin for a single year: the truth-eliding, life-cheapening strongman Joseph Stalin.

Indeed, while most know about and deplore Mr. Putin’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, it’s far easier to forget the even longer shadow left by the post-1945 Soviet takeover of Central Europe by guile, subversion and violence.

Perhaps lost to popular history – and certainly lost amid the mythmaking in modern Russia – is that when the Second World War began, Nazi Germany’s only serious ally, other than Benito Mussolini’s Italy, was Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Sevastopol, 2019: An elderly woman holds a portrait of Stalin during Victory Day celebrations in the Russian-held Crimean city.STR/Getty Images

Moscow, 1939: With Stalin standing behind him and a portrait of Lenin hanging above him, Soviet foreign commissar Vyacheslav Molotov signs a non-aggression pact with his German counterpart, Joachim von Ribbentrop, third from right.National Archives and Records Administration

On Aug. 23, 1939 – 80 years ago – Stalin and Adolf Hitler made a deal that set in motion the invasion and occupation of six countries. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a treaty of non-aggression signed at the Kremlin by Soviet and German foreign ministers in Stalin’s presence, included a “secret additional protocol” providing for Soviet and German spheres of influence covering Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (all bordering the Baltic Sea), while declaring the “interest of the USSR in Bessarabia,” then a part of Romania.

On Sept. 1, Nazi armies invaded Poland from the west. Just more than two weeks later, Soviet armies stormed in from the east. On Sept. 28, the two sides signed the German-Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, as well as two more documents around “common efforts" in Poland and its “repatriation and political subjugation.” Stalin subsequently annexed more than 200,000 square kilometres of Poland; Hitler claimed 92,500 square kilometres.

By November, Stalin had invaded Finland. In June, 1940, Soviet armies had occupied the Baltic states, followed later that month and in early July by the invasion, occupation and later annexation of northern Bukovina, Hertza and Bessarabia, then under the administration of the Kingdom of Romania and later incorporated into the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.

On Finland's eastern front on Jan. 18, 1940, camouflaged Finnish soldiers cluster in a trench during the Winter War with Russia. Two months later, a Finnish-Soviet peace treaty ceded some border territory to the USSR.The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Sadly, some of the deadly results of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact still endure: Parts of Finland, Latvia and Estonia annexed in 1940 remain part of the Russian Federation. Territories taken from Romania include today’s Moldova, as well as Chernivtsi Oblast and part of Odessa Oblast in Ukraine. But the pact’s role in adding fuel to the fire of world war was far greater.

While Stalin spent the two years in which the pact was in force occupying or annexing territory that today belongs to 10 European states, including Russia, the “subjugation” of Poland freed Hitler’s hand to invade Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and France. Drunk with victory in Poland and elsewhere, convinced that new “spheres of influence” agreed by totalitarian regimes were inevitable and distracted by the Winter War with Finland, Stalin utterly failed to foresee Hitler’s brutal and historic double-cross in Operation Barbarossa, in 1941. More than 28 million Soviet citizens perished in the resulting slaughter. About half were from what is today Russia; eight to 10 million were from Ukraine; two to three million from Belarus. At least 1.5 million died in Central Asia, and a million more in the Caucasus. One million died in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, whose illegal annexation was never recognized by Canada and most democracies.

In the rogues’ gallery of Second World War aggressors, Stalin too often gets overlooked. After all, when Hitler betrayed him, the Soviet Union became an ally of the United States, the United Kingdom, Free France and others. The Allied forces won the war – and the authority to write history and the narrative of their glorious role in it. But Hitler’s war on the Soviet Union exacted colossal, unimaginable losses partly because Stalin’s disastrous two-year dalliance with him made the Nazi dictator that much stronger.

Vilnius, May 9, 2019: People hold portraits of relatives who died in the Second World War on the 74th anniversary of Nazi Germany's surrender. The war's end brought Lithuania and the other Baltic states into the Soviet sphere of influence, which they would not escape until 1990-91.Mindaugas Kulbis/The Associated Press

St. Petersburg, May 9, 2019: Russian army servicewomen march during the Victory Day parade. The anniversary of Nazi Germany's surrender is Russia's most important secular holiday, a tribute to the 'Great Patriotic War' that also serves as a display of the nation's military strength.Dmitri Lovetsky/The Associated Press

Moscow, May 9, 2019: Mr. Putin and other participants in a Victory Day march on Red Square carry portraits of their relatives who fought in the Second World War.Alexander NEMENOV/AFP/Getty Images

While the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was a disaster for all concerned – above all, for Russia’s people – you’d never know that from listening to Russian officials today. Russia’s ambassador to Canada failed to mention the Hitler-Stalin alliance this year when he marked the start of the Nazis’ grim campaign and celebrated their eventual surrender in 1945, writing instead that “without the Red Army’s victory and the Allied comradeship-in-arms, Europe as we know it would have never existed.” And Mr. Putin’s hapless Foreign Affairs Minister, Sergey Lavrov, who has never been one to let facts stand in the way of odious sophistry, sought to pin blame for June, 1941, on “those who, by colluding with Hitler in Munich in 1938, tried to channel Nazi aggression to the east.” It’s a wonder Mr. Lavrov didn’t look to blame John Kerry.

This world, in which Stalin is a model, is the one Vladimir Putin now inhabits. While NATO allies debate the past and acknowledge mistakes – from the failure to stop Mussolini’s aggression in Ethiopia or Stalin’s famine-genocide in Ukraine to the legacy of Yalta – today’s Kremlin refuses to accept any criticism of either Stalin or Mr. Putin.

That’s because their actions have been so similar. Both added territory by force and both trusted in propaganda, disinformation and influence operations to close the deal. Mr. Putin has frequently repeated Stalin’s rationale for invasion and annexation: It was someone else’s fault. In a May news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, for instance, he said the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact “made sense for ensuring the security of the Soviet Union” after Stalin’s bid for an anti-Hitler coalition with Western countries failed. Mr. Putin also termed the pact “payback” for Poland’s own overtures to Nazi Germany. He justified the invasion and occupation of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014 in similar terms, as well as the illegal annexation of Crimea; these were necessary interventions, he said, because of the “unacceptable” breakup of the Soviet Union.

Free historical inquiry into the Second World War has been all but shut down in Russia. Mentioning the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland in the wrong context can lead to a heavy fine. Those who chart the fine filigree of conspiratorial complicity, totalitarian practice and violent intent that link Hitler and Stalin are condemned as heretics. Anyone opposing Mr. Putin’s aggression in Georgia, Ukraine or elsewhere is branded a Nazi. This reactionary climate makes for a stark and bitter contrast with 1989, when Soviet authorities first acknowledged and condemned the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, or the post-1991 period under Boris Yeltsin, when a critical spirit still governed discussion of what Russians call the Great Patriotic War.

Far from absorbing the lessons of Stalin’s deadly embrace of Hitler, today’s Kremlin is reprising it by illegally annexing territory, aggressively undermining democracy and vaingloriously touting a toxic cult of personality as a model for the world. The “end of history” – political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s vision of a perfect endpoint for concepts of human and sociocultural governance – has given way to the “end of logic,” with Stalin’s dark role now inspiring a widening tragedy under Mr. Putin.

Let’s be clear: The Russian chauvinists upon whom Mr. Putin relies are serious about their recycled neo-Stalinist doctrines, even if they lead to new confrontations and new conflicts. If this still sounds far-fetched, look no further than “The Long-Running State of Putin: On What Is Really Happening Here,” a long article published in Moscow’s unapologetically nationalist and therefore semi-official Nezavisimaya Gazeta in February by Mr. Putin’s long-serving top ideologist, Vladislav Surkov. In it, the Kremlin strategist justifies invasion, corruption and repression as a better model of governance in the name of a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Over almost three decades of working on Russian issues, living in Russia and studying Russian history, I have never read such a nauseating and dangerous rhetorical cocktail of patent nonsense.

Putin adviser Vladislav Surkov, shown in 2013.Mikhail Klimentyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool/via AP

The arc of Mr. Surkov’s career is also an illustration of how things have gotten here. He and a handful of relentless, ruthless and hubristic officials, together with a circle of oligarchs, have kept Mr. Putin in office by effectively making him a modern apostle of neo-Stalinism, all the while treading carefully in the waves that allow Mr. Putin to retain that title.

When I last met with Mr. Surkov, he was pushing papers in Mr. Putin’s Kremlin during Jean Chrétien’s Team Canada mission to Russia, working to instill discipline in oligarch ranks after the incarceration of his former boss, oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky. He went on to engineer the muzzling of independent media, before instituting the farce of Russia’s “managed democracy,” in which parties move through the political arena with all the spontaneity of an S-400 missile system parading through Red Square.

By 2011, with social media and the Arab Spring roiling the waters around dictators everywhere, Mr. Surkov had been dropped from the Kremlin on suspicion of having orchestrated anti-Putin demonstrations to keep now-Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev in the president’s role. But by 2014, as Ukraine made its historic break with Moscow’s tutelage, Mr. Surkov was back in office as the puppeteer-in-chief for Kremlin proxies in Ukraine – a motley crew of ex-military mercenaries, thugs and ne’er-do-wells whose actions have made Russia less popular in Ukrainian eyes than at any previous time in the two countries’ thousand-year histories of statehood. Now, he is one of the small group of aides upon whom Mr. Putin has depended continuously for 20 years, alongside the two dozen or so oligarchs who keep this team in power.

Mr. Surkov’s February article – a kind of “ode to dictatorship” that would have made many Stalin-era court poets blush – can be read as their disturbing and revealing manifesto. It confirms deep insecurity about Russia’s current international isolation and lacklustre economy. It signifies continuing blindness about realities in Ukraine. And it lays bare the Kremlin’s supremely misplaced confidence in its ability to upset the apple cart of market-based democracy. Shockingly, it is the work of a Kremlin that believes a neo-Stalinist agenda is a tonic for the whole world.

In Mr. Surkov’s dystopian vision, democratic choice is an illusion – a P.T. Barnum sideshow rejected by Russian society in favour of “the realism of predetermination,” or predestination. In other words, dictators are the destiny not just of Russia but the whole world.

Russia’s breaking apart, he says, was unnatural – it had to be stopped. Now Russia “has begun to re-establish itself and has returned to its natural and only possible condition as a great, expanding and land-gathering community of peoples.” In other words, Ukraine is just the beginning.

Post-Cold War American hegemony, he claims, was only ended by the “Munich speech.” Here, Mr. Surkov is not referring to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s blithe declaration in 1938 that he had secured “peace for our time” after a trip to Nazi Germany, but rather Mr. Putin’s speech in 2007 claiming Russia wanted peace; instead, he invaded Georgia in 2008.

Mr. Surkov argues that democracy only survives because of a “deep state” that, anonymously and unaccountably, restores equilibrium. Russia lacks a “deep state,” he says, but has a “deep people” who trust Mr. Putin because his system is “more honest.”

All of this means that the 21st century is turning out “our way,” in Mr. Surkov’s view, with “English Brexit, American #GreatAgain, and Europe’s anti-migrant retrenchment" representing only the start of “deglobalization, restoration of sovereignty and nationalism” now that "the bastards are everywhere.” The whole piece reads like a bad Steve Bannon infomercial. The implication that Donald Trump’s disastrous legacy and Russian fatalism will keep Mr. Putin in power is clear and repeated.

A woman holds a sign of Mr. Putin and Mr. Trump outside the White House in 2018. It is a parody of a Soviet-era poster of Stalin holding a baby.Andrew Harnik/The Associated Press

Not that the Kremlin is leaving things to chance. As Mr. Yanukovych was being airlifted to safety in Moscow in 2014, Kremlin-directed assets on social media sought to sow discord by bolstering the “yes” side of Scotland’s independence referendum. In 2015, Moscow worked to amplify extremist views of the migration crisis in Europe. It’s a mixed track record: Their assets successfully backed Brexit and Mr. Trump, but Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel were elected and re-elected despite industrial-scale Kremlin support for their opponents. Yet, there are more world leaders now in Mr. Putin’s image, from Italy’s Matteo Salvini to Hungary’s Viktor Orban. Over the past year, Kremlin-backed campaigns have even sown discord in Mexico, with a view to further polarizing U.S. opinion.

Still, in most democracies, from Finland to France, Russian interference has fallen flat. Defences have proven stronger; citizens are getting wiser. The European Union, the Atlantic Council, NATO and Anders Fogh Rasmussen’s Alliance of Democracies have launched major initiatives to counter its effects.

In other words, Russia’s blows have buffeted our democracies but have by no means broken them. On the contrary, there is in many quarters a new appreciation for how fragile and contingent our free institutions may be, which has inspired a firmer determination to defend them. Where apparent polarization shrank the middle ground of politics for a time, new initiatives are springing up aimed at community-building, citizen solutions, dialogue, accountability and competence.

In Vilnius, a mural shows presidents Mr. Putin and Mr. Trump, right, alongside Hitler, Stalin and President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, far right.Mindaugas Kulbis/The Associated Press

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks with Mr. Putin at the Paris Peace Forum in 2018.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

What do such Russian antics mean for Canada? A polarized Europe during the migration crisis of the summer of 2015 was a crucial backdrop for our last federal election, especially after the tragic death of three-year-old Alan Kurdi. Mr. Putin and his team were surely as delighted to see that Canadian government leave office – it had been instrumental in Russia’s ejection from the G8 and in the establishment of a tough sanctions regime – as they were to see the formation of the People’s Party of Canada, with its skeptical attitudes toward immigration.

But the challenges of 2019 are different. Russian interests are now more likely to be pushed by domestic players under foreign influence than by bot armies out of St. Petersburg. Social-media platforms, still so lax in rooting out such abuse, are increasingly seen as platforms worthy of derision. Courtesy and fact-checking are making a comeback, although most media business models remain distressed.

For Canada, the challenge is to promote substantive debate, free of disruption by malign actors, on issues that count most for our country today: markets and competitiveness, immigration, inclusion, sustainability and the advancement of Indigenous peoples. We also need to have a clear-eyed conversation about the new world we inhabit – one in which there are real partners committed to multilateralism and the UN’s global goals, as well as a growing number of dictatorships, explicit or camouflaged, waging proxy and propaganda wars. The simple antidote to dismissal, distortion, distraction, dismay and division at the hands of anonymous voices is accountable debate by real people, preferably in person. In other words, the solutions are more democracy and more transparency.

State-owned propaganda outlets, from RT and Sputnik to China Central Television, need to be given a wide berth. Google, Facebook and Twitter should be seen as part of the problem, not the solution, and regulated accordingly. Quality independent media, where journalists tell real stories that matter to all of us, deserve our eyeballs and our investment. The citizen who is not willing to pay a modest amount to open their mind to their country and the world runs the risk of flying blind.

Remember that in the world laid out by Mr. Surkov, Russian dictatorship is the new model for the entire globe. In this world, territory can be seized at will, and Russia is able to mess with our heads. That’s simply not the reality. After Mr. Yeltsin’s structural reforms, real wages grew by more than 10 per cent annually from 1999 to 2008, while GDP rose 7 per cent on average per year. Russia’s GDP today has barely grown since then; a country with three times China’s per-capita nominal GDP in 2013 now has barely $1,000 more. By every measure, Mr. Putin’s military adventures, as well as his twin policies of fear and corruption, have been utter disasters. Well-regulated markets, honest governments with progressive tax systems, political pluralism and free speech work much better, by definable, defensible metrics; their appeal has barely flickered despite the blast furnace of five years of industrial-strength propaganda. The countries, organizations and jurisdictions that have been targets are pulling through this test intact, if not stronger.

For all of Mr. Surkov’s cocksure rosiness, Russia may not do the same. As in the 1930s, ordinary Russians are again suffering asymmetrically profound hardship while dangerous pedants like him drone on about baubles in the “higher league of geopolitical struggle.” It’s enough to make one want to read the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact once more, this August – and then go out and support the nearest anti-disinformation initiative.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.