Photo illustration by The Globe and Mail (Source: Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam, 1512)

Randy Boyagoda is a professor of English at the University of Toronto, where he also serves as principal of St. Michael’s College. His most recent novel is Original Prin.

As a Catholic who has gone to Sunday mass in a school portable in small-town Protestant Arkansas, and in a tsunami-wrecked open-air shrine in Buddhist-majority Sri Lanka, this is the first time in my life that I have not been able to go to church – whether I wanted to, or not.

Stern words have been on my mind, these unprecedented weeks of church-less life and prayer. The source isn’t the Bible, or the Catechism, or the Pope, but instead a Greek Orthodox bishop I encountered in Silicon Valley a few years ago. We were both attending a conference on religion and technology. I don’t remember much about the various papers and conversations, save that they all felt timely and exciting; the attendees were charged with the sense that conventional religious practice needed both to accommodate, and be accommodated by, the means and ends of the new technocracy. Everyone also shared a sense that these needed efforts would accomplish the most, in word and spirit and deed, if they were pursued with more of an openness to newness and experiment than established religions and their institutions and representatives are normally known for. Indeed, the conference itself had been convened by the Vatican.

Notwithstanding the striking image he cut with his long black beard and long black robe, the Greek Orthodox bishop was generally a quiet and gruff-friendly presence throughout our bright days in blue-sky Santa Clara. This only changed during a panel discussion of what it might mean to experience God through icons in the digital era.

While icons feature in many religions and across Christianity, they retain a special significance in the Orthodox traditions, as irreducible, irreplaceable means of focusing individual prayer life. In their conceptually and actually textured depictions of holy men and women, icons invite and sustain layered and depth-seeking contemplations of God. While everyone on the panel acknowledged as much, in an obviously leading way one of the speakers speculatively questioned whether an icon encountered on an iPad could have the same religious status and capacities as an icon encountered in person. “Absolutely not!” the bishop declared from his seat off to the side, flashing righteous anger at the very notion that something so fundamental in its physicality could be substituted for something so fundamentally virtual. The holy free-spirited discussion ended there.

A Greek Orthodox priest leads Sunday Mass in the empty church of Agios Georgios in the Cypriot village of Pano Deftera, southwest of Nicosia, Cyprus's capital.IAKOVOS HATZISTAVROU/AFP via Getty Images/AFP/Getty Images

Whether it’s an icon or any other physical feature of conventional religious practice, these are not being experienced in person by most anyone around the world other than a few clergy, during these our shared COVID-19 trials and tribulations. That Greek Orthodox bishop’s stern words keep coming to mind because now, in a real way, with immediate demands and effects and implications, religious leaders and believers need to figure out what’s possible and not possible, what our commitments should newly entail and still should not.

After all, the most taken-for-granted and, for many, defining feature of faith life – spending time intentionally, with God and others, in a physical space, whether synagogue, church, mosque, or temple – is not possible and won’t be any time soon. Religious institutions in Canada and elsewhere have cancelled regular services and shut their doors for the foreseeable future, in conformity with broader practices of closing and physical distancing across our shared public life.

There has been some resistance, predominantly in the United States, to the perception and reality of government encroachments on religious liberties, and also a stronger pushback in the U.S. and elsewhere at the idea that religious services are not essential in a time of ultimate, life-and-death concerns. After all, churches across Europe remained open throughout the Second World War, even with bombs falling from the sky. But COVID-19 is a different kind of threat altogether, in light of how it spreads. Given all the many features of regular religious practice that involve close contact – dipping your fingers in holy water, sharing pews, shaking hands as signs of peace, receiving Holy Communion on palm or tongue, in just Catholicism alone – the voluntary agreement of church authorities to cease public, in-person offerings and gatherings makes good sense when it comes to safeguarding individual and collective health.

But what are the effects on individual and collective spiritual health? Obviously, and as in so many other parts of our lives, technology has become both an unprecedented help, if also unexpected hindrance, to viable and adaptive religious practices in the time of COVID-19. I recently listened to a BBC report on a virtual reality Christian service that – symptomatically – spent more time and attention on the tech that was being deployed and on the congregants’ warm, funny, glitchy globalized chatting, rather than on querying whether participants were able to commune with God and each other in any substantive way.

My own family recently livestreamed a special service from Rome: Pope Francis preached and prayed for the city and the world’s swift relief from the illness and its social and economic effects while standing at an altar before an empty, rain-swept St. Peter’s Square. In a very COVID-19 version of an impromptu pilgrimage, we moved through our house, switching screens, trying to stay ahead of the server pressure and web traffic that kept freezing Francis, mid-blessing.

At top, Pope Francis walks through an empty St. Peter's Square to give a special global blessing on March 27. It was watched around the world, such as in these households in (clockwise from top left) the Italian towns of San Fiorano and Cisternino; Guadalajara, Mexico; and Seattle, Washington.Photos: Reuters, AFP/Getty Images/Reuters, AFP/Getty Images

Beyond such special events and occasions, as a housebound family we are marking the hours of these otherwise anxious and shapeless-feeling days by way of regular morning and evening prayer. We have often done so – especially during the recurring times of great preparation in Christian life, Advent and Lent – but our efforts have always been in tension with getting ready for school and work, meals and bedtime. Right now, there’s not nearly the same pressure of such competing claims on our time and movement. But rather than everything going slack, together with our children we are more serious and committed to the few minutes every day that we spend lighting candles and commending to God those suffering directly from the illness, and those working to keep us safe, and those trying to find a cure.

This is all absolutely to the good, personally and collectively. In addition to the immediate effects it has on us, and any higher order efficacies it brings about, such experiences of seeking God while prevented from going to church also cultivate an otherwise rare sense of identification with the countless others, around our world today and across the centuries, who have been denied the right to practice their faith in its fullness, whether from state injustice or naturally occurring barriers. Moreover, these days we can perceive the very ancient reality of the domus ecclesia – given small numbers and under threat of persecution by authorities, the earliest Christian believers practised their faith in homes, hence the idea of a “house church.” Thinking positively about living out one’s faith in the time of COVID-19 leads in these directions. It also makes for unexpected discoveries of deeper connections and logics.

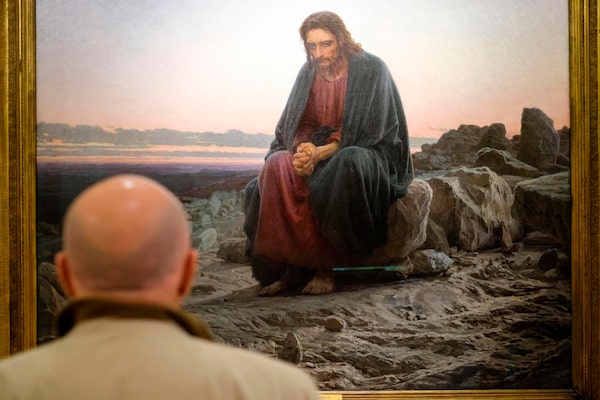

A man stops by Ivan Kramskoy's 1872 painting Christ in the Wilderness at the Vatican Museum in 2018. In the Bible, Jesus spends 40 days and nights in the desert facing temptation by Satan.Alessandro Di Meo/ANSA via AP/The Associated Press

For instance, the watchword of the moment, quarantine, comes from a practice, as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention explains, that “began during the 14th century in an effort to protect coastal cities from plague epidemics. Ships arriving in Venice from infected ports were required to sit at anchor for 40 days before landing. This practice, called quarantine, was derived from the Italian words quaranta giorni, which means 40 days.”

The number 40 didn’t come out of clinical trials or peer-reviewed research. Its source is sacred. And while there are many instances of meaningful 40-day periods in Scripture, the one that matters most in relation to both Lent and to our current sense of quarantine, as experiences of solitude and deprivation for the greater good, comes from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew. These both chronicle an important, indeed preparatory, stage in Christ’s earthly life, when he spent 40 days in the desert neither eating nor drinking, while also resisting the devil’s temptations to selfishness and the exercise of raw power. The place he went was named quarentena, according to the Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest-identified source for the word, which dates to the fourth century.

I have figured out all of this from my house, using books and browsers, and can make of it what I will, just as we are making the most of our daily prayer practices as a family. And if religious lives were predominantly based on such self-determined commitments, searches and experiences, the strictures placed on us by COVID-19 could be said to have some unintended positive consequences, at least in this area. But these aren’t our natural and normative religious lives, any more than distanced, detached, self-confined daily existence is natural and normative for humanity itself.

Such as you can call streaming mass attending mass (the future promises many theological debates over this), I have been “going” to church most weekdays while working from home, via the livestream 7:30 a.m. service celebrated by Toronto’s archbishop, Thomas Cardinal Collins, from an austere-feeling, effectively empty St. Michael’s Cathedral. The first time I did this, standing beside my wife, both of us wearing around-the-house athleisure, the viewer counter in the upper left of the screen showed 250 others were also “present.” A week later, the view count was closer to 1,500. It won’t surprise me if the count reaches into the many thousands this weekend, as Holy Week, the most significant period of the liturgical year, culminates in Holy Thursday, Good Friday, the Easter Vigil and Easter Sunday.

Archbishop Pierbattista Pizzaballa, middle, arrives for Holy Thursday ceremonies at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where Christians believe Jesus Christ was buried. This year, the ceremonies were held inside with no public attendance.Ariel Schalit/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

A Filipino Catholic prays outside a closed church on Holy Thursday in Manila, where religious services have been deemed illegal under measures enforcing home quarantine.Eloisa Lopez/Reuters/Reuters

In the midst of this, I intensely miss the transformative sensory experiences of being in church, especially at this time of the year – the sprinkling of holy water, the rustle of palms, the smoky perfume of incense, the glow of candles and ringing of bells, the simple, radical sustenance of the communion wafer. I am trying to be grateful that we can continue to participate in the universal life of the church, albeit in radically limited ways. But I am also dreading the spiritual and interpersonal mediocrity that doing so might encourage in me, in the lead-up to Easter, exactly the time when I prayerfully want to be open to more than that. This isn’t to say that just being in a church would guard against such mediocrity. By no means. Rather, being in a church and gaining access to the fullness of its offerings in person ensures that my experience of God doesn’t just depend on me.

Granted, it’s an amazing sign of worldwide Christian fellowship and the connective powers of technology when, as my family recently did, you can stream a Sunday mass celebrated in, say, a tiny chapel in Minnesota, with the comment bar on the side of the screen not only counting the hundreds and thousands joining the feed but also allowing them to post greetings and words of encouragement, alongside enthusiastic, emoji-filled announcements of their co-ordinates – Mumbai, Melbourne, Mississauga. This is all a predictable outcome of mediated mass-going and also a welcome source of unity in an atomized-feeling moment, provided it doesn’t distract and undermine the primary good of mass itself. That it was doing so, in my case, was easily dealt with: I simply minimized the comment bar and tried again to concentrate on the sacred words and actions.

But the distractions just became more immediate and were far more sensory in their own ways. I couldn’t minimize the family dog, which wandered into our impromptu home chapel and began chewing on a bottle of eyedrop medicine in the middle of the priest’s opening blessing. I couldn’t minimize the missing sock, Sharpie and charging cord I saw under a bookcase during the consecration of the bread and wine because I’ve never stared at my television from a kneeling position (even during major sporting events). I couldn’t encourage my children to a more prayerful repose because I couldn’t confidently establish what prayerful repose entails amid even the picked-up detritus of the family TV room. I couldn’t even work out whether to lower the shades: doing so would enhance picture quality on a sunny Sunday morning, and also avoid all the joggers and dog-walkers looking in and wondering what kind of weird family calisthenics we were doing. But even the idea of lowering the shades also intensified the desire to fidget with the picture quality and reconsider the definition rate, instead of concentrating on the mass itself. Worse, the lowered shades intensified the already-strong feeling of being shut away from the rest of the world, compounded by a sense we were hiding our religious identity and activity, which goes so strongly against the public and evangelical imperatives inherent to the message and traditions of Christianity.

A masked worshipper walks towards Jerusalem's Church of the Holy Sepulchre on Holy Thursday.Ariel Schalit/The Associated Press/The Associated Press

Such dilemmas for religious believers won’t go away any time soon, and certainly didn’t before the observances of Holy Thursday, earlier this week. Normally, we prepare a dinner of lamb and bitter-herb soup and eat it while wearing our shoes so that we can rush out the door to church. This sequence is meant to evoke and enact a local, Christian version of the events and practices associated with the original Passover feast, which Jews commemorate to this day to recall God’s freeing them from slavery in Egypt. Christ and his disciples also observed the Passover, in what came to be known thereafter as the Last Supper, an event that also instituted the priesthood and the Eucharist.

This year, we still did this – and also took turns washing the feet of our youngest daughter, inspired by Christ’s washing the feet of the disciples as a kind of loving humility and welcome to his house and fellowship, a practice that normally takes place at Holy Thursday masses and definitely didn’t this year, virtually or in person. We also did this, for her, as a way of acknowledging that she will be welcomed into a closer unity with God and the community of believers more fully at some point in an uncertain future: her first communion, originally scheduled for later this month, has been delayed indefinitely. Whether still wearing shoes or barefoot and damp, we all ran upstairs to the TV room to livestream mass. Doing so was joyful, yes, but it also threatened to feel foolish, even pointless.

And right there, right there, lies the great temptation. Because whether it’s in person or not, whether it’s before or during or after COVID-19, religious practices can always threaten to feel foolish and pointless. Does that mean that they are? Does that mean we should abandon millennia-old, ever-fresh ways of knowing and being known by God and one another? Does that mean giving up on such abiding and durable sources of sacrificial love and solidarity? Absolutely not.

A parishioner talks with a priest outside St. Dominic Catholic Church in New Orleans on Holy Wednesday.Chris Graythen/Getty Images/Getty Images

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.