An advertisement for an elixir promised to protect against influenza, published in the Daily Gleaner newspaper in Fredericton, on Oct. 18, 1918.Handout

Jane Jenkins is an associate professor and director of science and technology studies at St. Thomas University.

Spreading on social media these days, as fast as COVID-19, is a pandemic of disinformation. Conspiracy theories, false claims, and quack cures, emerging in step with the coronavirus, are as lethal as the virus on its own. In South Africa, disinformation posted on Facebook persuades people to avoid public health initiatives to test for the virus and tweets from conspiracy theorists claim that government-issued face masks contain poison. In North America, YouTube videos tout fake cures and unproven prophylactics: If you can hold your breath for 10 seconds you don’t have the virus but if you do fall victim, megadoses of vitamin C, lemons, zinc lozenges and anti-malaria drugs can cure you. U.S. President Donald Trump has also given voice to unproven cures, such as malaria drug hydroxychloroquine and injecting disinfectant. Peddlers of falsehoods and bogus cures such as these see opportunity in the uncertainty of a world turned upside down. Taking advantage of both fear and hope, disinformation can be used to grab power or push up profit.

Things weren’t much different on Canada’s East Coast during the 1918 influenza pandemic. When influenza swept into New Brunswick in the fall of 1918, people were already bone-weary from four years of war and it seemed incomprehensible that things could get any worse. Unfortunately, people were soon overwhelmed by fear of the invisible killer they called “the enemy in our midst” and stories that it came from a fog left by German U-boats just off Halifax seemed believable.

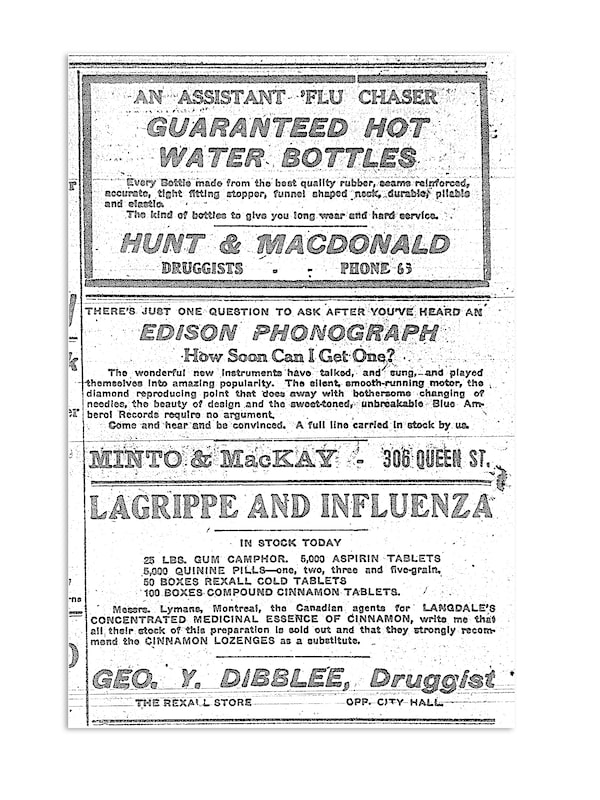

Ads published in the Daily Gleaner newspaper, published in Fredericton, Oct. 18, 1918.

In New Brunswick, Health Department officials tried to redirect attention away from conspiracy theories to public health management. They responded swiftly to the outbreak and within days of the first reported cases, issued orders to close all theatres, schools and churches and to prohibit large gatherings and meetings. Although shops and small businesses could remain open, customer flow was greatly reduced. The province had been shut down and it would stay that way for five long weeks.

Isolation, boredom and overwhelming dread replaced the usual routines of life that chilly fall of 1918. And feeding on this widespread anxiety were newspaper advertisements and articles trumpeting often outlandish remedies to prevent or cure influenza by keeping the right attitude, making recipes at home, or buying ready-made items. In most cases, the path to cure and comfort led straight to the clothes and other goods for sale in shops and stores.

Reassuring advice to stay positive had been sent out in step with early rumours of an epidemic. One newspaper editorial in the St. John Standard reassured readers cheerfully that “the epidemic will probably pass away as suddenly as it came.” And if, on the off chance, it did strike close to home, all one needed to combat it was a positive attitude and plenty of fresh air and sunshine.

Once the terrible epidemic had hit, however, a flurry of newspaper articles offered advice about how to deal with it. Protection could be as easy as eating three yeast cakes a day and maintaining a regular diet with plenty of onions. Exercise was important if one kept cool while walking and warm while bicycling. Breathe through the nose, not the mouth. Home-made flu preventatives required ample quantities of iodine and turpentine. Other preventatives came in the form of bags of menthol hung around the neck, with pink-coloured bags most likely to cheer up the wearer. The main thing was to avoid panic. Other recipes swore that mustard ointment and concentrated essence of cinnamon could keep out the dangerous seeds of disease.

Advertisements marketed a range of manufactured products, from gargles and nose sprays to lozenges, all of which should be bought in large quantities for frequent use. Wampole’s Paraformic Lozenges, at 25 cents a bottle, were touted for their protective value: “A tablet in the mouth protects against contagion in public places.” Johnson’s Anodyne Liniment was “Enemy to Germs” and good for the nose and throat. And it did double duty because, “with an occasional dose taken internally” it could “safeguard you from serious results and halt the evil in its first stage.” People recovering from flu could manage “After Flu-Effects and Weakness” with “Creophos – a fine combination of cod liver extract, hypophosphites and creosote.” And if you had enough money, you could rent a violet ray machine for $4 a week ($15 a month). This electro-therapy was already a popular remedy for everything from acne to kidney stones, but during the influenza epidemic it was plugged as the definitive cure.

From the Daily Gleaner newspaper, published in Fredericton Oct. 29, 1918.Handout

Shopkeepers who leveraged the influenza epidemic for profit sold more standard products. One clothing store, noting that “chances are all in favour of persons who do not fear the ‘demic,” recommended that people should “turn thoughts to Fall and Winter Clothing! Cheer Up! Don’t get Blue! Invest in Some New Clothes and Victory Bonds!” Another clothing store, headlining its ad with the claim that “Shakespeare Knew the Value of Sleep,” went on to thank the Health Department for closing theatres, bowling alleys and other places of amusement because this meant there was “Nothing to Do But Z-Z-Z” – in pussy-willow pyjamas and nightshirts that were “soft as a kitten’s wrist and only $2.00.” Stores selling footwear highlighted the need to keep feet dry and comfortable with new shoes or boots. Druggists guaranteed their hot water bottles were “assistant flu chasers.”

These ads prove that both fear and hope sell. And we see these age-old truths playing out again today. Another truth is that, long after the current COVID-19 pandemic fades away, falsehood and fabrication will endure, as the lethal sidekicks of all pandemics.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.