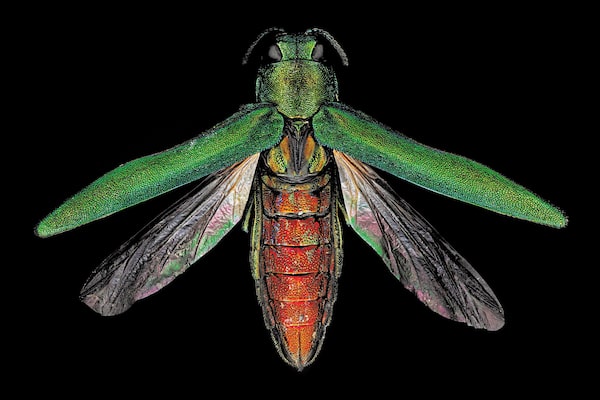

The emerald ash borer wiped out swaths of urban forests in cities such as Montreal and Toronto because the cities had planted mostly ash trees – its favourite food.WELLCOME COLLECTION

Peter Kuitenbrouwer is a journalist and registered professional forester who holds a Master of Forest Conservation from the University of Toronto.

Summer has arrived. And that has meant the revival of Canadians’ annual battle with bugs.

An entire shelf at our cottage sags with insect repellent, and ours is certainly not unique. For the past few years, warfare against the tree-leaf-eating spongy moth (the new name for the European gypsy moth) has gripped Ontario’s tree lovers and municipal officials alike, all while aphids, beetles and budworms lay waste to our forests.

For many years, we have fought this war on bugs, convinced we can triumph with the right insecticides. But who is winning? The bugs are still here. And bugs will always win until we accept that we, not insects, are the problem.

We simplify nature, cultivating tree monocultures that facilitate the feast for a specialist leaf, needle or bark eater. We let in foreign insects with no predators here, which then feed unchallenged. Perhaps worst of all, we celebrate an idealized, antiseptic version of natural beauty, and insist we can improve the wilderness by putting some of its inhabitants to death.

Vainglorious hostilities between insects and humans in our great outdoors date back more than a century. Laurentian University forest history professor Mark Kuhlberg has written a new book about this conflict titled Killing Bugs for Business and Beauty: Canada’s aerial war against forest pests, 1913-1930 – a thorough treatise that uncovers the odd motivations behind Canada’s pioneering work in aerial spraying against forest pests in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia.

Dr. Kuhlberg introduces us to wealthy U.S. and Canadian cottagers in Muskoka, Ont., from a century ago who, alarmed by the defoliation of hemlocks, lobbied Ontario officials to “bomb woodland pests with poison” because “the only way to save nature was to kill it.” Paper barons in Nova Scotia and resort owners in B.C. also pleaded for such death from the air, which went against what is now regarded as sound forest policy.

The result: toxic dusting of calcium arsenate and other chemicals in some of Canada’s most cherished natural areas, including Cape Breton Island, Muskoka, Vancouver’s Stanley Park and the Seymour Canyon in North Vancouver – the city’s source of its internationally renowned, previously untreated drinking water.

The book offers lessons for today about the effort that’s wasted when we allow emotions, rather than science, influence how we care for the environment. It also raises intriguing questions about the selective perception of some “nature lovers,” who love certain parts of nature but want other parts dead.

Canada’s aerial attacks on insects emerged after our victory in the First World War, when the country found itself with an air force and no place to strafe. So we found a new enemy: the natural world. According to Dr. Kuhlberg, in May, 1925, agriculture minister William Motherwell told the House of Commons that in “the next great war,” Canada would deploy chemicals against bugs.

Maclean’s magazine chimed in: “all the world knows of Canada’s bitter sacrifice and splendid accomplishments in the last great war, yet even Canadians know little of a far greater war … against a power more colossal, more implacable than Germany ever dreamed of being.” That adversary? Insects. A headline in The Globe and Mail in 1925 warned: Budworm Scourge Menaces Entire Coniferous Forests. (Newspapers had a motivation to combat a bug that eats evergreen trees, the raw material of newsprint.)

Just after the summer solstice in 1927, Canada pioneered the aerial spraying of forests. Royal Canadian Air Force Flying Officers T.M. Shields and C. Bath flew a Pennsylvania-built Keystone Puffer from a base at Whycocomagh, N.S., and over the course of two weeks, they dropped close to several tonnes of calcium arsenate and lead arsenate on a forest on Cape Breton Island leased to the U.S.-owned Oxford Paper Company. The chemicals’ target was the spruce budworm, which is native to Canada: the most destructive pest of spruce and fir forests in North America.

Was the toxic bombing overkill? Perhaps not; the forests indeed had a big bug problem. But the very hungry caterpillars were fated to return. As Malcolm Swaine, a federal forest entomologist at the time, pointed out in the Forestry Chronicle in 1926, mills had selectively cut spruce, which was preferred to make paper. This wiped out the seed crop for future spruce, and encouraged the rise of balsam fir. The misnamed budworm, which prefers fir, would likely have hardly believed its luck: Loggers had effectively curated a buffet of its favourite food.

“If the trained foresters do not find a way of keeping the old balsam utilized and if possible increase the percentage of spruce in the stands,” Dr. Swaine wrote in a letter to another forester, “the fault will lie with them.”

Writing last year in Ontario Woodlander magazine, Christian Messier, a professor of forest ecology at the Université du Québec en Outaouais, repeated this point: “a great diversity of tree species increases the resilience of forest to disturbance.”

In cities, urban forest policy often ignores this advice and favours monocultures that become vulnerable to pests. Cities in the early 20th century loved the perfect umbrella canopy of shade offered by American elm trees. Along came elm bark beetles and destroyed them. Montreal and Toronto, among many cities, repeated the monoculture mistake with ash, a lovely and resilient street tree. The emerald ash borer sneaked in, probably buried in a shipping pallet from Asia, and joyously wiped out huge swaths of urban forests again because we served the beetle a continuous snack of ash, its favourite food.

Urbanization, meanwhile, begat cottagers, a species of nature enthusiasts who worship the untouched wilderness even as they seek ways to perfect it.

A century ago, an attack by the native hemlock looper led wealthy cottagers in Muskoka to beg for an aerial shower of taxpayer-funded toxins. Albert Wilks, a cottage owner on Lake Joseph, wrote to government officials in 1927: “If you could see the fine hemlocks dying by the hundreds on Chief’s Island, as I can, from our docks, you would be filled with regret as I am.”

Why this crisis mentality? In nature, trees die. Dead trees, Dr. Kuhlberg points out, were even used to promote Muskoka: An engraving from 1879 showing the splendour of Muskoka’s rocky islets, covered with both living and dead trees. Dead trees serve as vital animal habitat, sheltering up to 1,000 species of wildlife. But cottagers, Dr. Kuhlberg writes, “could not tolerate bearing witness to their stands of trees perishing.”

So they called in the bombers. In some cases, they even cared more for their trees than those who treated them: When the planes flew over Muskoka in 1928 and 1929, calcium arsenate, disbursed from a hopper in the plane’s nose, flew back into the open cockpit, blinding and poisoning the pilot.

During the same period, the hemlock looper attacked the Seymour Canyon north of Vancouver, where the untreated water was “crystal-pure and sparkling,” boasted B.C. newspapers at the time, in contrast to the chlorinated water in the likes of Toronto. But to fight the looper, the province called in the planes.

George Hopping, a forester working for Canada’s Division of Entomology, feared aerial dusting might poison the water supply; after all, Greater Vancouver Water Board rules even forbade “spitting or blowing noses onto the ground” in this hallowed watershed. And yet, Dr. Kuhlberg marvels, Boeing B1E Flying Boats dumped 16,000 pounds of calcium arsenate on the canyon in the spring of 1930 – and while there were no reports of water tests after the mission, Vancouver now chlorinates its water.

Unfortunately, it appears we have learned nothing. This May and June, per an $800,000 non-competitive contract with Zimmer Air Service Inc., a helicopter sprayed much of Toronto, including my neighbourhood, with 5,440 litres of a solution containing the insecticide Btk to combat the spongy moth (also known by its Latin name, Lymantria dispar dispar or LDD), which in the past three years has devoured many tree leaves across the city. A helicopter also sprayed High Park with the insecticide BoVir.

This was the wrong decision. Earlier spikes of spongy moth infestations had lasted about three years, after which populations of the moth plunged for about a decade; 2021 was the third year of the cycle. Second, city foresters conceded that Btk can kill beneficial and native caterpillars, a food source for birds. To justify the 2022 spray campaign, the city conducted its own surveys of egg masses, but also quoted the Ontario government as claiming “this is the worst infestation in Ontario in 30 years,” with a link to the provincial website. However, a map on that site of “projected 2022 LDD moth defoliation” predicted less damage than last year, and suggests Toronto was at low-risk for the moth this year.

Perhaps Toronto sprayed based less on logic and more in response to public pressure, just as provincial officials caved to anguished cries from Muskoka’s cottagers a century ago. We cannot know whether the spongy moth would have returned without the spraying, but what I can say is that last year, the spongy moth devastated our family’s forest in Madoc, Ont. We didn’t spray this year, and the caterpillar did not come. Our cool spring helped end the infestation.

Don’t get me wrong: I love my Deep Woods Off. Still, that repels my adversaries, rather than killing them. The problem with declaring war is that you can lose, or end up in a protracted campaign with casualties all around. Peaceful co-existence, or at least a cessation of hostilities and an acceptance of the other’s right to persist, can be better for all involved.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.