A golfer tees off at the Loch March Golf & Country Club in Ottawa, on the first day of golfing in Ontario as the province begins to ease restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, on Saturday, May 16, 2020.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

If you’d asked Chelsey McDowall 12 months ago what she thought of golf, it’s unlikely she would have minced words. “When I was growing up, I mean, my dad always watched all the important tournaments on TV,” she recalled the other day. “And they last what seems like weeks.” She and her sister played soccer and rugby and basketball, and a few years ago McDowall, 27, fell hard for CrossFit. But golf? That was very clearly, “an older-guy-sport kind of thing.”

Then COVID-19 hit, the world shut down for a couple of months, and when it started to open again, well, guess what was left standing?

And so, last June, McDowall’s father dragged her out to Turnberry, a public course in Brampton, Ont., to take a few swings at the driving range. “Nothing else to really do with our time,” she explained. The next day, she took a lesson with an instructor: It was more fun than she’d expected. “I guess it just kind of opened up my eyes,” she said. The day after that, her dad took her to Golf Town and bought her a set of clubs. Over the next couple of months, she took some more lessons and played a couple of rounds with a friend. Golf content started to pop up in her Instagram feed, posted by people – often women – she never would have figured for players. By the end of the summer, she was hooked.

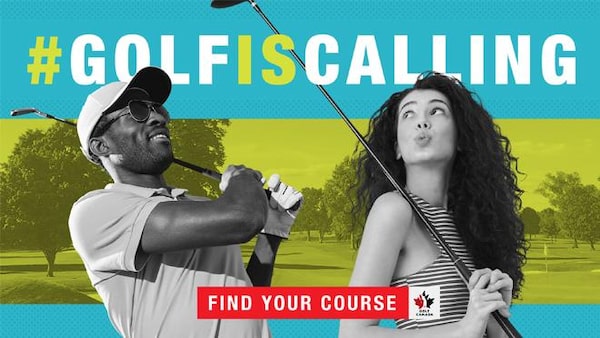

Images from Golf Canada’s “Golf Is Calling” marketing campaign.Handout

Hundreds of thousands, many of them first-timers, joined McDowall, flooding Canada’s roughly 2,300 courses last year, pushed there by a unique virus-induced combination of work-from-home flexibility, golf’s family friendly nature and government-mandated emergency measures that barred many other athletic pursuits, including team sports.

At first, the industry was caught flat-footed. When most provinces gave the all-clear for courses to open in May, booking systems crashed. Half-decent tee times were scarce. “You needed to book six or seven days in advance,” said Ryan Browne, a low-handicap golfer who lives in northern part of Brampton. Tensions spilled over onto the course. “Some of the places weren’t managed as well as others, there were people yelling at each other, not enough carts available,” Browne recalled.

But when the season wrapped up in the fall, industry leaders were breathless and agog at what they’d witnessed. Membership sales had soared. Courses had been packed from 7 a.m. to close.

Images from Golf Canada’s “Golf Is Calling” marketing campaignHandout

Just as astonishing, new players such as McDowall defied the sport’s long-standing reputation as an old, male bastion: 65 per cent were female, and 65 per cent were in the 18- to 34-year-old demographic, according to research conducted last fall for Golf Canada, the national sports federation and governing body for the sport. After years of little to no growth, industry executives and others are looking at 2021 as a chance to refresh golf’s reputation, boost revenue, eliminate some practices that were hurting operators, and finally reinvest in aging infrastructure. They talk of a rare – perhaps once-in-a-lifetime – opportunity that COVID-19 has given them.

They just don’t want to say that out loud. After all, there’s still a pandemic on.

Golf executives in Canada like to talk about how it’s the country’s No. 1 participation sport, played by about 5.7 million people. But that figure masks a decades-long stagnation during which the number of rounds played dropped to 57 million in 2019 from 67 million in 1996. A 2012 study for Golf Canada showed indifference to the game among most of its players.

Still, the game had found its feet again after a disastrous stretch amid the 2008 financial crash, when a raft of clubs closed. By 2020, “there had been a couple of years that we saw basically no erosion, and a slight marginal uptick,” said Stephen Johnston, the founding partner of GGA Partners, a golf and leisure industry consultancy.

A golfer tees off at the Cardinal golf club Wednesday May 20, 2020 in Laval, Que.Ryan Remiorz/The Canadian Press

Then COVID-19 created an ideal set of conditions for the game’s comeback. Office workers no longer tethered to their downtown desks could break away to shoot a quick round in the middle of the day. Health authorities preached the importance of spending time outside. Team sports were largely cancelled. So were most other forms of out-of-home entertainment, travel and leisure. And for those who still had jobs, golf was one of the few sectors in which they could spend suddenly available disposal income.

Government lobbying helped pave the way. “We spent a lot of time with all the provincial governments across the country, positioning golf,” said Jeff Calderwood, the chief executive officer of the National Golf Course Owners Association Canada (NGCOA). ”Golf is just nicely positioned as a 15-kilometre walk over 150 acres with three other people you know well that can easily social distance. It’s part of the solution to all those pandemic issues that are facing everybody.”

It was a tough start: Because most courses were closed until the middle of May, 2020, the number of rounds played across the country was down 38 per cent as of June 1, 2020, compared to the average of the previous five years, according to data compiled by the NGCOA. But by the end of October, the overall number of rounds played ended up 18 per cent.

The surge reached all areas of the business. Joanne Anderson, the golf instructor who gave Chelsey McDowall such a nice introduction to the game, saw her volume of business roughly double, to more than 180 lessons last year from about 90 in 2019. Retail sales of golf equipment in the United States increased 10.1 per cent according to Golf Datatech. (Canadian figures are not available.) TWC Enterprises Ltd., a publicly traded company which operates dozens of clubs in North America under the ClubLink brand, reported its new-member sales in Canada jumped almost 113 per cent year-over-year, to 2,145 in 2020 from 1,008 in 2019.

Not all courses across the country benefited: resorts and other destination courses suffered because of travel restrictions.

But many clubs had such a gush of business they introduced waitlists for the first time in decades. “Waitlists were almost a thing of the past,” said Joe Murphy, General Manager and COO of Thornhill Golf & Country Club, which capped its unrestricted memberships that allow players to book any tee time through the week.

So, now what?

Last fall, Golf Canada commissioned research on those who came out for the first time, or returned after years away, to help a retention marketing campaign for the 2021 season. Still, a number of executives from across the industry who spoke with The Globe and Mail said they did not want to be seen to be celebrating the sport’s windfall, given the horrific toll of COVID-19.

Last month, Vanessa Morbi, the chief marketing officer for Golf Canada, said during the organization’s annual general meeting that, in launching the retention campaign, “we need to ensure … that we continue to be extremely sensitive of the disastrous impacts of the pandemic, which has had a significant emotional and mental toll. It’s decimated entire industries.”

Still, she could hardly contain her enthusiasm. “As a marketer, I’m always looking to influence behaviour and harvest intent,” she said during a presentation to members. “COVID has offered us an unparalleled opportunity to do both.” She added: “As a marketer, you do not see these moments that often. We have a moment, and it is certainly not one to miss.”

The campaign kicked off last month with a funky, upbeat 30-second ad that feels as though it could be a spot for a high-end non-alcoholic seltzer: racially diverse thirtysomethings teeing off, laughing over post-game drinks, the crack of a beverage can, someone racking up Instagram likes with a pose from a golf cart.

The research, said Morbi, indicated that new players hit the course last year, “for friends, for family, for social purposes. It really wasn’t about competition. It really wasn’t about the sport of it.” Those players saw golf “as a really great day out with your friends. It’s really that sort of lifestyle elements of the sport that we saw loud and clear in the research.”

Behind the scenes, the industry is working to serve the new and returning players. And though long-time golfers may bristle, people in the industry say the changes will be better for everyone. As an example, when COVID-19 forced courses to take reservations, they were able to demand up-front payments. That all but eliminated no-shows, which used to leach about 10 per cent to 14 per cent of available inventory.

As well, for many years, public courses leaned on online discounting services such as GolfNow, a dominant Florida-based operator, and UnderPar to sell off their unused inventory. But the practice ate into courses’ revenue, and made it more difficult to develop relationships with customers. Courses are now taking back that inventory and, with it, more control over their own fate.

Industry experts also say that, with many courses operating at capacity, they’ll likely expand what is known as dynamic pricing, the practice used by airlines and concert promoters to better match prices with demand.

All of which will cost golfers more but also enable owners to upgrade their sometimes shopworn facilities. “Golf courses are not cheap to maintain. Irrigation systems, everything wears out,” Johnston said. “From 2008 on, the owners did not have as much excess cash to put back into their properties. And so they started to look a little old at times.” With new revenue, “it actually becomes a healthier property, because they can put money back in. They can modernize things.

“For patrons, it will be a better experience.”

And with COVID-19 looking likely to keep Canada in its grip for a while, golf has at least one more season to cement bonds with new and long-time players. “This isn’t going to be a light switch that’s going to turn off when we all get vaccinated, everything goes back to what we perceived to be normal,” Murphy said. “I think we’re going to see a demand for golf for the foreseeable future.”

Simon Houpt

Simon Houpt