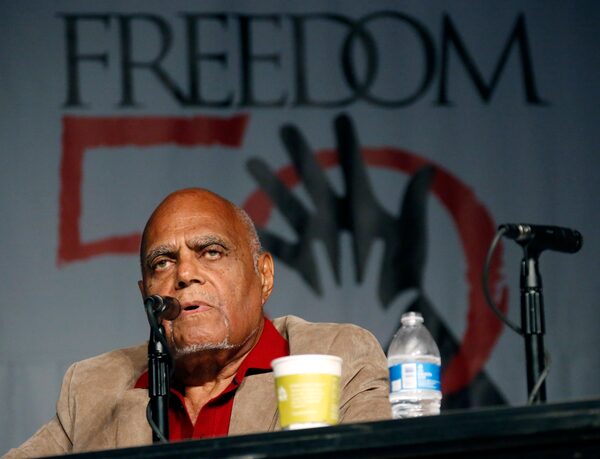

Robert Moses helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to challenge the all-white Democratic delegation from Mississippi in 1964.Rogelio V. Solis/The Associated Press

Bob Moses, a soft-spoken pioneer of the civil rights movement who faced relentless intimidation and brutal violence to register Black voters in Mississippi in the 1960s, and who later started a national organization devoted to teaching math as a means to a more equal society, died Sunday at his home in Hollywood, Fla. He was 86.

His daughter Maisha Moses confirmed his death. She did not specify a cause.

Mr. Moses cut a decidedly different image from other prominent Black figures in the 1960s, especially those who sought change by working with the country’s white political establishment.

Typically dressed in denim bib overalls and seemingly more comfortable around sharecroppers than senators, he insisted he was an organizer, not a leader. He said he drew inspiration from an older generation of civil rights organizers, such as Ella Baker, a leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and her “quiet work in out-of-the-way places and the commitment of organizers digging into local communities.”

“He exemplified putting community interests above ego and personal interest,” said Derrick Johnson, the president of the NAACP. “If you look at his work, he was always pushing local leadership first.”

In 1960, he left his job as a high-school teacher in New York for Mississippi, where he organized poor, illiterate and rural Black residents, and quickly became a legend among civil rights organizers in a state known for enforcing segregation with cross burnings and lynchings. Over the next five years, he helped to register thousands of voters and trained a generation of organizers in makeshift freedom schools.

White segregationists, including local law enforcement officials, responded to his efforts with violence. At one point during a voter-registration drive, a sheriff’s cousin bashed Mr. Moses’s head with a knife handle. Bleeding, he kept going, staggering up the steps of a courthouse to register a couple of Black farmers. Only then did he seek medical attention. There was no Black doctor in the county, Mr. Moses wrote, so he had to be driven to another town, where nine stitches were sewn into his head.

Another time, three Klansmen shot at a car in which Mr. Moses was a passenger as it drove through Greenwood, Miss. Mr. Moses cradled the bleeding driver and managed to bring the careening car to a stop.

Arrested and jailed many times, Mr. Moses developed a reputation for extraordinary calm in the face of horrific violence. Taylor Branch, author of Parting the Waters, a Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the early civil rights movement, told The New York Times in 1993 that “in Mississippi, Bob Moses was the equivalent of Martin Luther King.”

Although less well known than some of his fellow organizers, such as King, Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis, Mr. Moses played a role in many of the turning points in the struggle for civil rights.

He volunteered for and later joined the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, where he focused on voter registration drives across Mississippi. He was also a director of the Council of Federated Organizations, another civil rights group in the state.

Mr. Moses also helped to start the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer Project, which recruited college students in the North to join Black Mississippians in voter registration campaigns across the state, according to the Martin Luther King Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

Their efforts that summer were often met with brutal resistance. Three activists – James Chaney, who was Black, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who were white – were killed in rural Neshoba County, Miss., just a few weeks after the campaign began.

That same year, when Black people were excluded from the all-white Mississippi delegation at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, N.J., Mr. Moses helped create the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought recognition as the state’s delegation instead.

Mr. Moses, King, Ms. Hamer and Bayard Rustin negotiated directly with Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, who was running for vice-president. Although King favoured a compromise in which the Freedom Party delegates would be given two seats alongside the all-white delegation, Mr. Moses and other Freedom Party leaders held out for full recognition.

Mr. Moses later recalled that he was in Mr. Humphrey’s suite at the Pageant Motel when Walter Mondale, Minnesota’s attorney-general and head of the party’s credentials committee, suddenly announced on television the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party had accepted the “compromise.”

“I stomped out of the room, slamming the door in Hubert Humphrey’s face,” Mr. Moses recalled in the book Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project, which he wrote with Charles E. Cobb Jr.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Mr. Moses called the convention a “watershed in the movement” because it showed support from the party’s white establishment was “puddle-deep,” and he despaired over the possibility of building a biracial coalition that also bridged class divisions.

“You cannot trust the system,” he said in 1965. “I will have nothing to do with the political system any longer.”

Robert Parris Moses was born on Jan. 23, 1935, in New York, one of three children of Gregory Moses, a janitor, and Louise (Parris) Moses, a homemaker.

In a 2014 interview with Julian Bond, Mr. Moses credited his parents with fostering his love of learning, recalling they would collect books for him every week from the local library in Harlem.

He was raised in the Harlem River Houses, a public-housing complex, and attended Stuyvesant High School, a selective institution with a strong emphasis on math. He played basketball and majored in philosophy and French at Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y..

He earned a master’s degree in philosophy in 1957 from Harvard University, and was working toward his doctorate when he was forced to leave because of the death of his mother and the hospitalization of his father, according to the King Institute. He moved back to New York, where he taught math at the private Horace Mann School in the Riverdale section of the Bronx.

Already active in the local civil rights movement, he left for Mississippi after seeing scenes in the news of Black people picketing and sitting at lunch counters across the South. The images “hit me powerfully, in the soul as well as the brain,” he recalled in Radical Equations.

His natural confidence and calm demeanor drew people to him, and he soon became something of a civil rights celebrity. He was a hero of many books on the movement, and an inspiration for the 2000 movie Freedom Song, starring Danny Glover.

Eventually, the fame got to be too much – not only because it added to the stress of an already overwhelming task, but also because he thought it was dangerous for the movement. He resigned from the Council of Federated Organizations in December, 1964, and from SNCC two months later. He was, he said, “too strong, too central, so that people who did not need to, began to lean on me, to use me as a crutch.”

Mr. Moses grew active in the movement against the Vietnam War, and in April, 1965, he spoke at his first anti-war protest, in Washington. “The prosecutors of the war,” he said, were “the same people who refused to protect civil rights in the South” – a charge that drew criticism from moderates in the civil rights movement and from white liberals, who worried about alienating then-president Lyndon Johnson.

Not long afterward, he received a notice that his draft number had been called. Because he was five years past the age limit for the draft, he suspected it was the work of government agents.

Mr. Moses and his wife, Janet, moved to Tanzania, where they lived in the 1970s and where three of their four children were born. After eight years teaching in Africa, Mr. Moses returned to Cambridge, Mass., to continue working toward a doctorate in the philosophy of mathematics at Harvard.

In addition to his wife and daughter, Mr. Moses leaves another daughter, Malaika; his sons, Omowale and Tabasuri; and seven grandchildren.

When his eldest child, Maisha, entered the eighth grade in 1982, Mr. Moses was frustrated that her school did not offer algebra, so he asked the teacher to let her sit by herself in class and do more advanced work.

The teacher invited Mr. Moses, who had just received a MacArthur “genius grant”, to teach Maisha and several classmates. The Algebra Project was born.

The project was a five-step philosophy of teaching that can be applied to any concept, he wrote, including physical experience, pictorial representation, people talk (explain it in your own words), feature talk (put it into proper English) and symbolic representation.

“He understood that the literacies necessary for the 21st century were very different from the ones needed in the Industrial Age,” said Courtland Cox, a veteran civil rights leader and a friend of Mr. Moses’s.

By the early 1990s, the program had stretched to places including Boston and San Francisco, winning accolades from the National Science Foundation and reaching 9,000 children.

Mr. Moses saw teaching “math literacy” as a direct extension of his civil rights work in Mississippi.

“I believe that the absence of math literacy in urban and rural communities throughout this country is an issue as urgent as the lack of registered Black voters in Mississippi was in 1961,” he wrote in Radical Equations.

In the summer of 2020, when the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis touched off global protests against systemic racism and police brutality, Mr. Moses said the country seemed to be undergoing an “awakening.”

“I certainly don’t know, at this moment, which way the country might flip,” Mr. Moses told the Times. “It can lurch backward as quickly as it can lurch forward.”